How early humans' quest for food stoked the flames of evolution

Human evolution and exploration of the world were shaped by a hunger for tasty food – “a quest for deliciousness” – according to two leading academics.

Ancient humans who had the ability to smell and desire more complex aromas, and enjoy food and drink with a sour taste, gained evolutionary advantages over their less-discerning rivals, argue the authors of a new book about the part played by flavour in our development.

Some of the most significant inventions early humans made, such as stone tools and the controlled use of fire, were also partly driven by their pursuit of flavour and a preference for food they considered delicious, according to the new hypothesis.

“This key moment when we decide whether or not to use fire has, at its core, just the tastiness of food and the pleasure it provides. That is the moment in which our ancestors confront a choice between cooking things and not cooking things,” said Rob Dunn, a professor of applied ecology at North Carolina State University. “And they chose flavour.”

Cooked food tasted more delicious than uncooked food – and that’s why we opted to continue cooking it, he says: not just because, as academics have argued, cooked roots and meat were easier and safer to digest, and rewarded us with more calories.

Some scientists think the controlled use of fire, which was probably adopted a million years ago, was central to human evolution and helped us to evolve bigger brains.

“Having a big brain becomes less costly when you free up more calories from your food by cooking it,” said Dunn, who co-wrote Delicious: The Evolution of Flavour and How it Made Us Human with Monica Sanchez, a medical anthropologist.

However, accessing more calories was not the primary reason our ancestors decided to cook food. “Scientists often focus on what the eventual benefit is, rather than the immediate mechanism that allowed our ancestors to make the choice. We made the choice because of deliciousness. And then the eventual benefit was more calories and fewer pathogens.”

Human ancestors who preferred the taste of cooked meat over raw meat began to enjoy an evolutionary advantage over others. “In general, flavour rewards us for eating the things we’ve needed to eat in the past,” said Dunn.

In particular, people who evolved a preference for complex aromas are likely to have developed an evolutionary advantage, because the smell of cooked meat, for example, is much more complex than that of raw meat. “Meat goes from having tens of aromas to having hundreds of different aroma compounds,” said Dunn.

This predilection for more complex aromas made early humans more likely to turn their noses up at old, rotten meat, which often has “really simple smells”. “They would have been less likely to eat that food,” said Dunn. “Retronasal olfaction is a super-important part of our flavour system.”

The legacy of humanity’s remarkable preference for food which has a multitude of aroma compounds is reflected in “high food culture” today, Dunn says. “It’s a food culture that really caters for our ability to appreciate these complexities of aroma. We’ve made this very expensive kind of cuisine that somehow fits into our ancient sensory ability.”

Similarly, our proclivity for sour-tasting food and fermented beverages like beer and wine may stem from the evolutionary advantage that eating sour food and drink gave our ancestors.

“Most mammals have sour taste receptors,” said Dunn. “But in almost all of them, with very few exceptions, the sour taste is aversive – so most primates and other mammals, in general, will, if they taste something sour, spit it out. They don’t like it.”

Humans are among the few species that like sour, he says, another notable exception being pigs.

At some point, he thinks, humans’ and pigs’ sour taste receptors evolved to reward them if they found and ate decomposing food that tasted sour, especially if it also tasted a little sweet – because that is how acidic bacteria tastes. And that, in turn, is a sign that the food is fermenting, not putrefying.

“The acid produced by the bacteria kills off the pathogens in the rotten food. So we think that the sour taste on our tongue, and the way we appreciate it, actually may have served our ancestors as a kind of pH strip to know which of these fermented foods was safe,” said Dunn.

Human ancestors who were able to accurately identify rotting food that was actually fermenting, and therefore OK to eat, would have had an evolutionary advantage over others, he argues. If they also figured out how to safely ferment food to eat over winter, they further increased their food supply.

The negative consequence of this is that fermented, alcoholic fruit juice, a sort of “proto wine”, would also have tasted good – and that probably led to horrific hangovers.

“At some point, our ancestors evolved a version of the gene that produces the enzyme that breaks down alcohol in our bodies, which is 40 times faster than that of other primates,” added Dunn. “And so that really made our ancestors much more able to get the calories out of these fermented drinks, and it would also probably have lessened the extent to which they had hangovers every day from drinking.”

Flavour also drove humanity to innovate and explore, Dunn says. He thinks one reason our ancestors were inspired to begin using tools was to get hold of otherwise inaccessible food that tasted delicious: “If you look at what chimpanzees use tools to get, it’s almost always really delicious things, like honey.”

Having a portfolio of tools that they could use to find tasty things to eatgave our ancestors the confidence to explore new environments, knowing they would be able to find food, whatever the season threw at them. “It really allows our ancestors to move out into the world and do new things.”

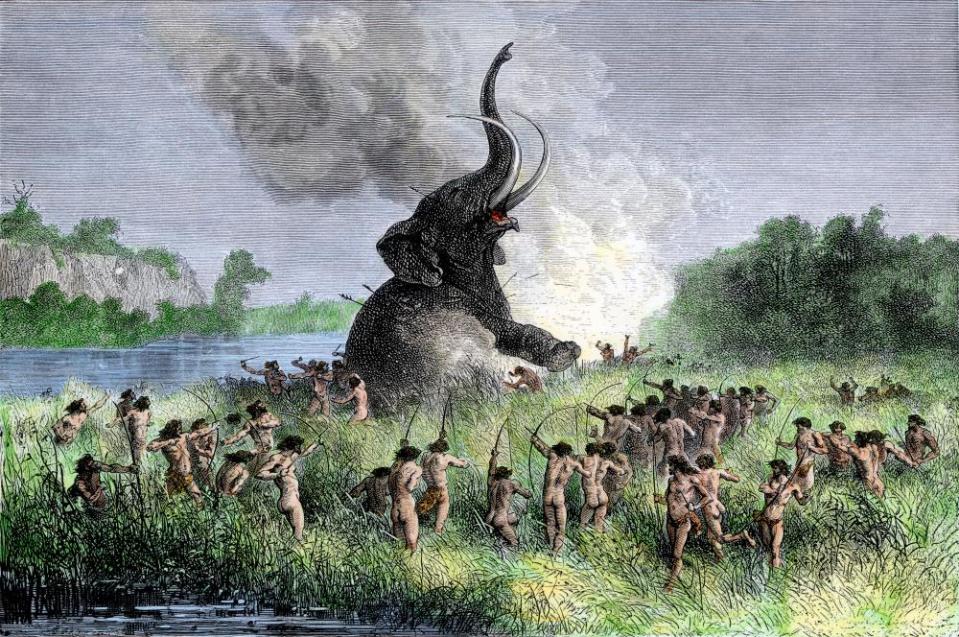

Stone tools in particular “fast-forward” the ability of humans to find delicious food. “Once they can hunt, using spears, they have access to this whole world of foods that were not available to them before.”

At this point, Dunn thinks humanity’s pursuit of tasty food started to have terrible consequences for other species. “We know that humans around the world hunted species to extinction, once they figured out how to hunt really effectively.”

Dunn strongly suspects that the mammals that first went extinct were the most delicious ones. “From what we were able to reconstruct, it looks like the mammoths, mastodons and giant sloths all would have been unusually tasty.”

Related: Paleolithic diet may not have been that 'paleo', scientists say

To replicate the eating habits of prehistoric humans, the book, published later this month, details how one scientist dropped a horse who had just died into a pond and assessed how it fermented over time. “He would sample some meat to see if it was safe to eat. He described it as delicious – a little bit like a blue cheese,” said Dunn.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies