Drugs 'trilemma': how to halt the deadly trade while still ensuring development and peace

The deaths of 25 people in a police raid on drug gangs in Rio de Janeiro have brought the “war on drugs” in developing countries into sharp focus once again. The raid on a favela in the Jacarezinho area of the city represents one of the deadliest police operations in Rio in recent years and has been condemned by the UN, which has called for an independent investigation.

This violence is but one incident in a “war on drugs” being enacted in many parts of the world in which thousands have died and that has generated tremendous harms – not least to the health, livelihoods and human rights of poor communities living in the borderlands of drug-producing countries.

Given these harms, it has become increasingly mainstream to advocate for approaching drugs as a development issue, so that drug-related goals are more aligned with the development and peacebuilding objectives of the UN’s sustainable development goals, which provide “a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet”.

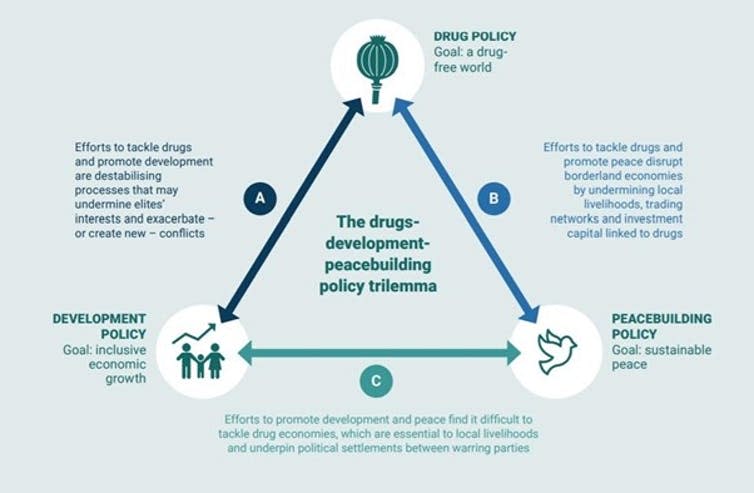

New research on drugs, conflict and development in the borderlands of Afghanistan, Colombia and Myanmar shines a spotlight on the tough trade-offs and the potential pitfalls of integrating the competing policy goals of eradicating the illegal drugs trade, securing peace and ensuring sustainable development – something that tends to get skirted over or hidden in policy debates.

For example, efforts to tackle drugs and development may undermine business and political interests and create new conflicts that undermine peacebuilding efforts. Take the revenues generated by the drug economy in the borderlands of Nimroz, Afghanistan that have cemented political coalitions and in doing so created a modicum of order. Attempts to tackle drugs through prohibition and interception or securing borders have been destabilising and contributed to a rise in violence.

Similarly, efforts to tackle drugs and establish the conditions for peace may undermine the livelihoods, trading networks and investment capital that has sustained development processes. For example, in the frontier region of Putumayo in southern Colombia, the coca economy is a mainstay of the local economy. Fumigation and forced eradication, without alternative investments in infrastructure and development programmes, have had a devastating effect on livelihoods.

And efforts to promote development and set conditions for peace cannot also tackle drug economies, which are central to local livelihoods and political settlements.

Efforts to bring an end to violence may involve unsavoury deals with vested political interests. For example, in Myanmar, opportunities to generate revenue from the drug economy were an important part of ceasefire agreements between the state and some armed groups dating back to the late 1980s. At the same time, the stability created by the ceasefires enabled more intense mining and logging. These development processes have driven new forms of dispossession and poverty that have forced many households to rely on opium cultivation to stave off destitution.

This leads to difficult questions about what kind of peace can be built in drugs-affected borderlands. There are tensions between peace built on forms of “elite capture” – where elites monopolise the benefits of peace and leave little scope for real change – and more progressive and inclusive forms of peace.

It also emphasises the need to better understand the uneven distribution of costs and benefits surrounding large-scale development strategies and to address the role that drug cultivation can play in alleviating poverty.

The tensions and trade-offs inherent to this “drugs-development-peacebuilding policy trilemma” are also shaped by place and time. Policies that appear to generate benefits at the national level may produce significant costs for borderland populations. Ostensibly successful efforts at drug reduction may simply push the problem over borders. For example, the success in reducing levels of opium cultivation in Thailand and Laos was based partly on the fact that cultivation subsequently expanded across the border in Myanmar.

There is also a “temporal trade-off” in that what appears to work in the short term – for example, sudden reductions in drug production – may unravel in the long term, leading to a rapid bounce-back in drugs production and markets. This means thinking carefully about how different policies are sequenced and combined.

For example, in Colombia, our research suggests that if coca farmers had access to legal markets for crops such as coffee and cacao and public goods including services and security, they would no longer cultivate coca. But the key point is that their version of “development” and “peace” would need to come before drug eradication.

Read more: Cocaine: falling coffee prices force Peru's farmers to cultivate coca

Changing the metrics and criteria of “success” and reassessing the timeframes involved and the sequence of measures taken are likely to make this trilemma easier to handle. It may be possible to pursue all three goals – reducing drugs, inclusive economic growth and sustainable peace – if they are not approached simultaneously, but in a sequenced and gradual way.

So it’s less about policymakers making mutually exclusive choices than it is about calibrating different policies so that they are more attuned to local contexts, needs and priorities.

Our research also highlights the need to keep the role of policy in perspective and “turn the mirror inwards”. Policymakers typically see themselves as external to the contexts they are engaged with. This often prevents them from assessing their own position within, and influence on, these contexts. The policy trilemma is not primarily about the technical issues related to “best practice”, sequencing and efficiency. At the heart of policymaking is the question of who decides on the trade-offs and who benefits and loses out as a result of these decisions.

Policymakers must acknowledge more explicitly their own roles and interests in these processes. Interventions are likely to fail or generate further negative effects where responses being imposed from outside – whether internationally or at the national level – fail to mesh with the needs of local people.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jonathan Goodhand receives funding from the Global Challenges Research Fund, ESRC

Patrick Meehan receives funding from the ESRC.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies