I don't believe in Mother's Day, but I'm hoping for at least another mother's decade

What’s your first memory of your mother? Mine, at first blush, would seem to indicate why I shrug at Mother’s Day.

I was maybe 5, the eldest of five, and I was done with our mother. As I explained to my next-in-line sibling, she was so dictatorial, and we should run away to teach her a lesson. This was probably the last time my brother Truong blindly followed me. But he helped me pack clothes and some food. Then we heard Mom calling our names.

We were middle class, but this was Saigon in the 1970s and most households had live-in maids. The housekeeper had overheard us and squealed. Instead of being angry or scared, our mother, towel drying her long hair after washing, was cool in the soupy humidity. She even smiled as she said that if we really wanted to leave, leave. And she turned away to care for our younger siblings.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

Truong and I stood there, holding our bags. He let me know he had changed his mind. I was humiliated and livid, but I decided to return her bluff. Let’s go, I told him, and started walking out the door.

My legs were shaking. “Miss,” I heard the housekeeper hiss, “they’re really going!” Mom called our names again. We quickly turned around. She was trying to keep a straight face as she said she had decided to forgive us and let us stay. I decided it would be wise to let her.

Vietnamese moms, American moms

After my family fled the fall of Saigon in 1975 and the Mount of Olives Lutheran Church sponsored us to Phoenix, I learned the phrase “motherhood and apple pie.” American TV showed all these moms who hugged and kissed and who loved so unconditionally, I thought all American mothers must be different from Vietnamese mothers.

Our first winter in America, the church members rang the doorbell one night and surprised us – with a Christmas tree they taught us to decorate right then, presents to put under it, decorated cookies and a big bowl of eggnog. Suddenly, the pastor's wife asked where my mom had gone. We found her in my parents' bedroom in tears, and at 9 years old this scared me because I had never seen my mother cry.

But she couldn't believe that people who looked nothing like us and who weren't connected to us by blood at all could be so kind. It was a very movie sort of scene, the spirit of Christmas just like those American films my parents used to take us to see during the war: the pastor's wife coming into the bedroom to comfort Mom and bringing her back out to the living room, then everybody coming up to hug her. It was actually hilarious – my mom, who's rarely affectionate, wrapped in the arms of all these foreign men and women!

I was still thinking as my daddy's girl. Dad talked to me about poetry, literature, religion, philosophy and dreams. Mom scolded me for daydreaming and not concentrating on grades, chores and acting like a girl.

She should talk. My mom's one of 15 children, with only four boys, and it wasn't until the seventh child that the first son was born. My mom was child No. 3, and by that time my grandfather was already so desperate for a son, he dressed her like a boy and told her that boys don't cry. Once she was old enough to enter grade school, her parents dressed her as a girl. But even in her teens, wearing the traditional Vietnamese high school uniform of a white high-neck tunic with front and back panels over white pants, Mom tied those fluttery panels out of the way before she bicycled home – unlike all the ladylike girls who folded the back panel over their lap before pedaling.

Here’s another question for you: Does our first memory of our mothers age as we age? I’m about to turn 55, and my first memory of my mom can’t be from when I was 5.

This is a woman who, in Vietnam, had children in five consecutive years and survived a war. Who, to help Dad get us off welfare in Arizona as soon as possible, took the first jobs she could, as a housekeeper and a restaurant dishwasher, before getting trained to work on an electronic assembly line.

Who, when a white boy in a car next to us at a red light pulled his eyes to make fun of Asians, stuck her tongue out and then laughed at him. Who, after Dad passed away, retired early to help care for my children so I could go back to work. Who not only has taught me how to parent but also how to live.

From Vietnam to Virginia

In 2009, Mom’s mother died at 90 in Phoenix, and she was the last of my kids’ great-grandmothers to pass away. I couldn’t help comparing her life with the other great-grandmas: two women from Vietnam and two from America.

What struck me was that the two Vietnamese women shared a culture but lived very differently from each other, and that the two Americans might as well have come from different planets. I decided to try writing a historical fiction book, and I interviewed my mom as well as my parents-in-law about their mothers.

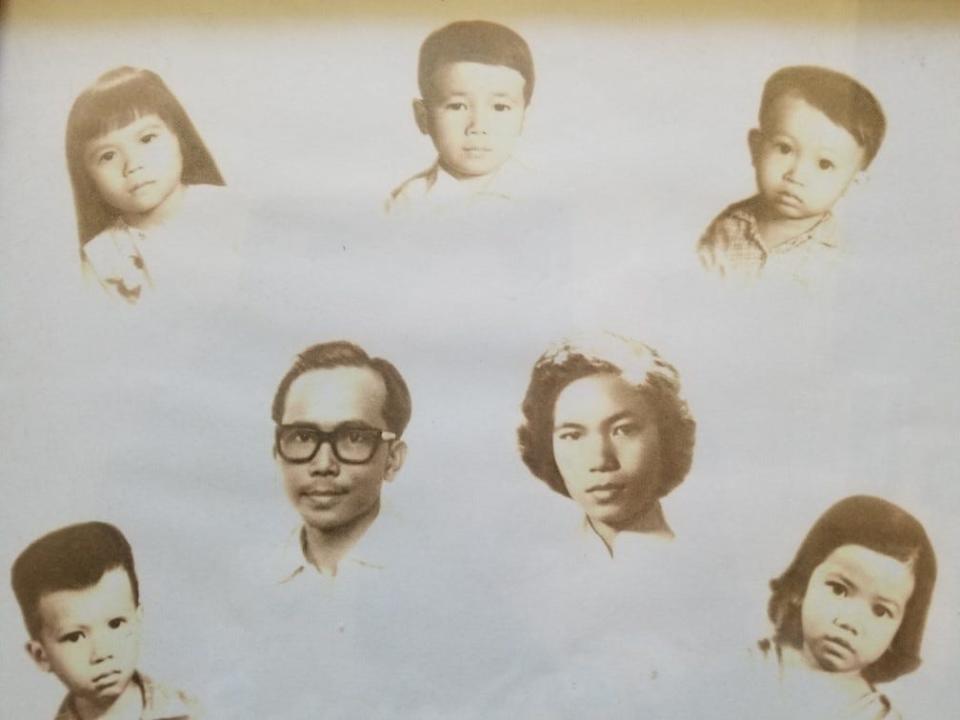

My dad had already passed away, but the onetime newspaper editor and hobby photographer left behind plenty of family stories and pictures.

Surprise! The four women who inspired my fictional novel were all far from natural-born mothers. Neither American was “motherhood and apple pie,” and both Vietnamese treated raising children as a job.

I worked on this novel over a decade, during which my eldest of four children matured from a tween to a college graduate and my youngest grew from toddler to tween.

Many nights after working as a copy editor for the USA TODAY opinion section, I’d come home, put the kids to bed and head to my vanity table (appropriate for a vanity project), where I’d open my laptop and channel my grandmothers and my husband’s grandmothers. No, I wasn’t a superwoman. I had help: We were living with my parents-in-law as well as my mom.

Listening to Mom, Duc Le, talk about her mother, Ty Vu – who in Hanoi had helped run the family bookstore, soap factory, trucking business, etc.; and then in 1954 had to start over when her family was among a million people who escaped communist North Vietnam and resettled in South Vietnam – I heard myself. I recognized our relationship, a rebellion that grew into admiration and a love that’s so protective, I can’t bring myself to express in any card.

Somewhere during my years as a commuter student to Arizona State University, I came home and walked in on my mother reading my journals. My heart stopped, thinking of all those times I documented climbing out of my window to go on high school dates and ditching ASU classes to drive a couple of hours to see my boyfriend in Tucson.

She looked up and said that I must hide my journals better because if my dad learned what I had been up to, it would break his heart. From then on, Mom treated me with respect like never before. I realized then that I had also been my mother's daughter all along, a pragmatic planner on how to realize my dreams.

Though I still cry easily, I've grown wary of knee-jerk passions and the pressure that profit-goal greeting card companies build around these emotional days that are supposed to remind us to express love.

Calling my mother's bluff, again

My most recent memory of my mother, who now lives near us in Northern Virginia in an independent living complex for the retired, is from this spring. Having dodged COVID-19 with masks, quarantine, not hugging her grandchildren, not being able to spend nights with us and finally being vaccinated, she was diagnosed with cancer. Again.

She survived colon cancer surgery in 2014 and escaped with no chemo or radiation, but now that she’s 80, she feared she didn’t have the strength to go through it all for a second time. Laparoscopic hysterectomy promised faster recovery, however, and the surgeon and I explained that it’s either this or maybe three more years – but the last year would be the cancer slowly, painfully destroying her uterus.

And the hospital, despite the pandemic, agreed to let masked me stay with her to translate for as long as she had to be there. The laparoscopic surgery worked, but because of her prior colon operation scars, she needed additional surgeries to stop the bleeding.

After her third operation in 24 hours and multiple blood transfusions, I was allowed to return to her bedside and was told her blood pressure was too high. I looked at my ghostly, unconscious mother and thought, it’s all my fault; I talked her into this and now I’ve killed her. I held her hand and stroked her skin. Please don’t punish me, I thought. Please don’t leave me. You don’t want to leave me. You can’t leave me.

I decided to call her bluff. I kept stroking her hand and prayed to her. “Mrs. Le,” I heard the nurse say to my mom, “your blood pressure is coming down! You decided to wait for your daughter, huh?” My mother didn’t bat an eye; she didn’t move. But the green, digital numbers continued to back down. Silently I pleaded, come back to me; I can’t see you in pain like this again; come back to me and let me show you I’ve learned my lesson.

And now, after a week in the hospital, another week in rehab and a month of full recovery, apparently she’s decided to let me. If I’m lucky, we’ll have at least another mother’s decade.

Thuan Le Elston, a member of the USA TODAY Editorial Board, is the author of "Rendezvous at the Altar: From Vietnam to Virginia," to be published this September. Follow her on Twitter: @thuanelston

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Happy Mother's Day? Doesn't matter. Why I want another mother's decade

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies