Disabled Kansas City woman blasts governor as ‘tyrant’ for ending $300 unemployment

At 55, disabled and “infuriated,” Ann Butner spoke with indignation.

“I want to ask him, who gave him the right to be czar?” she said of Missouri Gov. Mike Parson, who announced that he would no longer as of June 12 allow the state to give its unemployed workers the supplemental $300 per week checks approved by the federal government.

Under the American Rescue Plan, those checks were supposed to continue through Sept. 6. Missouri is among at least 12 Republican-led states now ending them in June or July, they say, to spur people back to work and jolt a still-lagging economy.

Parson on Tuesday held that many businesses statewide are struggling, “not because of COVID-19, but because they can’t find people to fill the jobs to help address this labor shortage.” The same day, Kansas Sen. Roger Marshall led nine other Republicans to introduce legislation to repeal the $300 increase across the country.

While people were in need during the heart of the pandemic, he said, “we should not be in the business of creating lucrative government dependency that makes it more beneficial to stay unemployed rather than return to work.”

On Thursday, Kansas Republicans announced they are looking to follow Missouri.

“Who gave him the right to be a tyrant,” Butner continued about the governor, “to just thumb his nose at the federal government and say, ‘Take your money,’ without considering how it affects everybody in the state?”

By “everybody,” the Kansas City widow means people like her living on a precarious financial ledge to whom the added $300 extra jobless benefits (in Missouri, the maximum weekly is normally $320; in Kansas, $488) was not extra money or mad money.

“It was survival,” Butner said.

Other complicating factors remain: finding good care for children or extended family, for example, or a lack of transportation.

Of course, Butner knows that issue of unemployment during COVID-19 is complicated, particularly as infections and deaths lessen, vaccinations increase and mask mandates are eased nationwide.

‘Get off your butts: Work’

Before COVID-19 struck in March 2020, 5.7 million people were out of work nationwide, a rate of, at 3.5%, among a string of record lows.

One month later, some 23 million people soon found themselves jobless. The unemployment rate, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, spiked to nearly 15%.

Today, jobs are opening up. Hiring signs hang in store windows across the area. Restaurants are having such a difficult time finding workers, some are offering bonuses as hiring incentives.

“We actually have more open job postings right now as compared to pre-pandemic,” said Mike Beene, director of employment services for the Kansas Department of Commerce. The kansasworks.com job site, he said, currently has about 41,000 openings, 12,000 in the Kansas City area. “Honestly, it’s all sectors right now that are in need of talent. … You can’t really put a finger on one sector or one industry that needs talent. They all are.”

The unemployment rate in April was 6.1%, although some caution that the number may be misleadingly low, as it does not include some 6.6 million workers who want jobs, but are no longer on the unemployment roles because they’ve stopped looking and weren’t counted in the previous four weeks. Officially, the roles now count 9.8 million Americans still out of work, 4 million of them for at least six months.

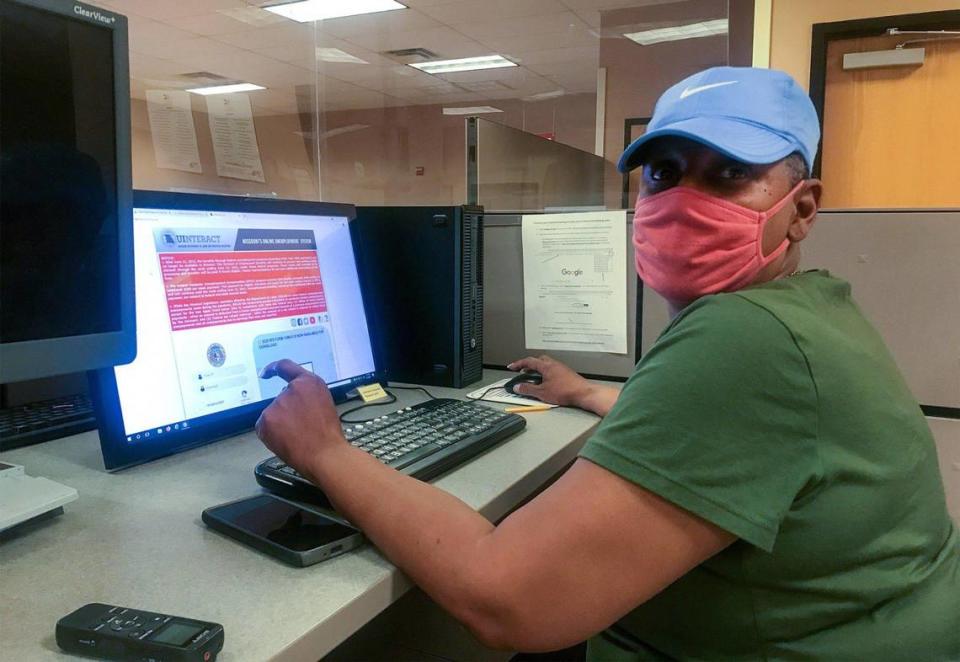

Even as Butner spoke this past week, Lisa Clark, 55, also of Kansas City, was on a computer at the Full Employment Council’s job center at 1740 Paseo Blvd. A former dispatcher, single, living on her own, she also worked giving hospice care during the pandemic. Clark said she believed that the extra employment benefits, first $600 per week and then $300, were vital to help people survive during the worst of the pandemic.

But now, she doesn’t think so. The previous week alone, she said, she applied for at least 50 jobs, for dispatcher and other positions. She scrolled through her phone, full of positive responses. She was setting up interview after interview.

“Everybody’s hiring,” Clark said. “There’s no problem finding a job. It’s time to get up. This is a young country. This is America. We have young, able-bodied people. Very intelligent. Teachers worked. Police worked. Get off your butts: Work.”

Butner said that she does not doubt, as the GOP claims and Democrats refute, that the added benefit has kept some people from returning to the workforce — better to stay at home and get unemployment rather than work a low-wage job.

Butner said she is not one of them. Taking away the added $300 in June, rather than in September — is not forcing her to get back to work.

It is doing the opposite: keeping her from returning to work.

‘Living on the edge’

Deemed fully disabled, Butner said, she has for years endured radiating pain down her legs from deep and complicated back surgeries that kept her from sitting for long stretches. That took her away from regular office work about 10 years ago.

Now on Social Security disability, she receives about $1,900 monthly for all her bills — her $1,000 monthly rent, heat, electricity, food, insurance, phone. Because she barely makes ends meet, she decided three years ago to become an Uber driver for a few hours on certain night and weekends.

She couldn’t sit long, but even a little time brought in extra money that helped with bills. But once COVID-19 hit, her Uber time was over.

The added jobless benefits made a massive difference. Her goal, in the end, was to try to save some of it, as much as $4,000, in order to buy and pay the taxes on a newer car, as Uber requires drivers to have cars that are less than 10 years old. Her 2001 Hyundai Accent had hit that limit.

But now, without the money, she said she does not have the down payment for a better car.

“I’m back to living on the edge,” Butner said.

Richard von Glahn, a policy director for Missouri Jobs With Justice, a workers’ rights organization, thinks that taking away the added benefit now is wrongheaded.

“I think this is a foolish decision,” von Glahn said. “I don’t know why you would block federal money from coming back to the state because, of course, people who are unemployed are going to use that money at local grocery stores, to stay up on their mortgages, stay up on their rent, stay up on their utility bills — things that cause serious disruptions.

“So from an economic standpoint, it makes zero sense.”

COVID stole her livelihood

For Jennifer Yardley, 50, of Grain Valley, the extra money has been a needed lifeline and one that she wished was continuing even for a short while.

She has worked as a hair stylist for 30 years and has owned her own business, Classic Touch Salon in Blue Springs, for some 20 years. Then COVID-19 struck. Her customers were older.

“Everything was going pretty good,” Yardley said this past week, checking on her unemployment at the Full Employment Council job center in Independence. “And then all this hit and we had to just go home and sit there.”

Her husband, who works making parts for Harley-Davidson motorcycles, was furloughed.

Her 19-year-old daughter lives with them, along with her baby and boyfriend. Yardley also cares for her other daughter’s 4-year-old son, having adopted him as her own.

She tried to go back to the salon after a few months. But her clientele was reluctant. The rent on the salon was mounting. Light, air conditioning, water, inventory cost money she didn’t have. Even with the added benefit, money was short. The young children needed shoes and clothes. Her daughter’s boyfriend had gotten a job at a fast food place right before the pandemic, and was one of the first to be let go when indoor dining stopped.

After 30 years, she closed her salon.

“It was hard. Really hard,” Yardley said. “We didn’t have money for rent. We had to get on food stamps because there wasn’t enough money for food.”

Yardley said she had only been in that position one other time in her life, when she was 18 and pregnant and living in Kansas.

“But when you’re almost 50 years old, you don’t really think you’re going to be doing that, you know?” she said. “Even though they gave you the extra money, it wasn’t like extra money for me. Because I got kids, you know what I mean?”

Her husband recently was called back to work, which will help, as they remain in debt. Yardley said that she is now looking for other jobs as well. If she goes back into hair styling, she would probably have to rent a booth, which costs money. She would need to rebuild her clientele nearly from scratch.

She’s applied to hotels and is thinking about McDonald’s.

“I mean, if I have to, I will,” Yardley said. “Whatever I have to do to feed the kids and take care of what I’ve got to do.”

When the pandemic struck, the Full Employment Council was forced to close down five of its eight job centers. On Monday, all eight will be open for the first time. They are anticipating a steady flow of clients seeking work or training.

Knew this was coming

Clyde McQueen, chief executive officer of the council, is agnostic regarding whether ending the added $300 unemployment is right or wrong. His take is that in September, it was going to come to an end, nonetheless, and his job is to be prepared to help people get back into the workforce.

“This has accelerated the inevitable,” McQueen said. He said there are jobs out there. Their data shows that the average salary of jobs obtained through the council, which covers five Missouri counties, averaged about $17 per hour.

“Just this morning,” he said, “somebody came (to the council) and said, ‘Hey, I’ve got 50 jobs that pay $25 an hour.’”

Not all jobs can be filled by anybody. Getting people to those jobs may require training, McQueen said, figuring out transportation for those who may have lost their cars because of financial hardship, or arranging day care. Many day care sites closed for good under the financial strain of the pandemic.

“We knew it was coming,” McQueen said of the end of the benefit. “We just didn’t know it was coming this soon. Still, we’ve got to prepare for it.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies