How Quebec's 1995 referendum was a turning point for racist comments in political discourse that's still felt

Standing on a stage in Montreal Wednesday night, singer Allison Russell recalled what it was like to live in the city after the Parti Québécois lost the referendum 27 years ago.

"I was spat on, called a monkey and told to go back to Africa," Russell, who is Black and was born in Montreal, told the audience.

In defeat, former premier Jacques Parizeau had blamed the 1995 loss on "money and ethnic votes."

Russell, who was 17 at the time, said the comments sparked racist acts in the streets and contributed to her decision to move away shortly afterward. She compared the remark to recent comments about immigration made by Coalition Avenir Québec candidate Jean Boulet and party leader François Legault.

The topic has dominated political discourse in the last days and weeks of the campaign.

In a local debate on Radio-Canada last week, Boulet — who serves as both the province's labour and immigration minister — said "80 per cent of immigrants go to Montreal, don't work, don't speak French or don't adhere to the values of Quebec society."

After Radio-Canada brought the comments to light this week, Boulet issued an apology on Twitter, saying he misspoke and that the statement about immigrants not working and not speaking French "does not reflect what I think."

Legault said Boulet didn't deserve to keep the immigration file if re-elected. But Legault himself said Monday that welcoming more than 50,000 immigrants per year would be "a bit suicidal," referring to the protection of the French language.

Earlier this month, Legault apologized for citing the threat of "extremism" and "violence" as well as the need to preserve Quebec's way of life as reasons to limit the number of immigrants to the province.

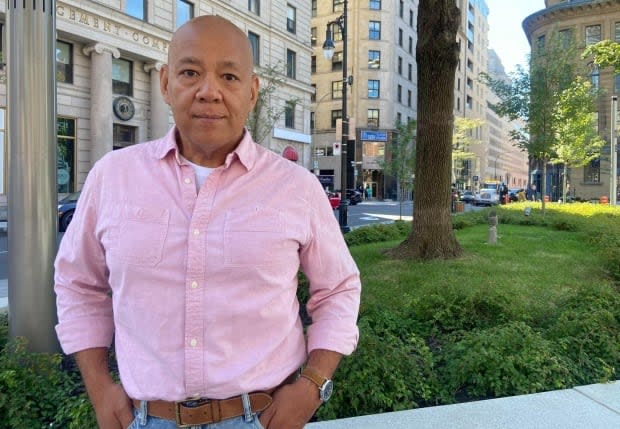

Aly Ndiaye, a Quebec-city based historian and rapper also known as Webster, said he sees the 1995 referendum loss and Parizeau's remark as a turning point for Quebec nationalism that made way for the kind of things Boulet and Legault have said this election campaign.

From inclusive nationalism to a change in Quebec identity

In the 1960s and 70s, Quebec's nationalist movement was intent on being progressive and inclusive, Ndiaye said. The movement was inspired by decolonization and revolutions happening across the world at the time — it was looking "outward," he said.

"After Parizeau, there was a closure," Ndiaye said. Quebec nationalism turned inward, he added.

"There started to be a more exclusive vision of Quebec identity... That's what Legault represents."

What worries Ndiaye is the fact that such comments are rarely labelled as racist, despite the fact that they stem from a vision of society that sees immigrants and their descendants as "second-class citizens."

"The Legault government is a racist, xenophobic and Islamophobic government," Ndiaye said. "It's aberrant."

Hate calls

Fo Niemi, who founded the Montreal Center for Research-Action on Race Relations (CRARR) in 1983, said he remembers the Parizeau moment clearly.

"I almost fell off my chair," he said.

Niemi said the centre received hate calls in the days following the Oct. 30, 1995 vote and stopped answering the phone for two or three days as a result.

When it comes to racist comments made in this year's provincial election, Niemi said that while there is a possibility they could lead to violence, or aggression against immigrants, they could also lead to an overall negative attitude in Quebec toward immigration and immigrants.

"Let's be clear, we're not talking about all immigrants. We're talking about immigrants who are clearly identifiable, i.e. non-white immigrants."

He agrees with Ndiaye about the hesitation to name racism.

"They don't call a spade a spade," Niemi said, calling the CAQ remarks "dog whistle politics," which refers to the use of messages that convey a particular — usually racist — sentiment to a target audience.

Evelyn Calugay, who runs PINAY, a Filipino women's rights group, said she remembers hearing about comments made to people in her community as well as to people of Chinese descent in 1995.

Stuff like, "You don't know how to speak French? Go back to where you belong, where you came from," Calugay said.

"They will always have somebody to blame and the people they have to blame are always the minorities, the marginalized — because they are a bunch of racists to me!" she said with a bit of a laugh.

Calugay came to Quebec in 1975 to work as a nurse. She is 76.

What happens after the election?

The CAQ isn't the only party to have come under fire for anti-immigrant sentiments. Comments about Quebec Muslims from Parti Québécois candidates Lyne Jubinville, Suzanne Gagnon and Pierre Vanier and his wife Catherine Provost have surfaced in the past two weeks.

Vanier, the candidate for Rousseau, and Provost, the candidate for neighbouring L'Assomption, were both suspended by PQ Leader Paul St-Pierre Plamondon Friday for posts they made on social media, one of which questioned the intelligence of Muslim women who wear head scarves.

Whatever the election result Monday, Niemi says his concern is what will happen afterward.

"Are we going to talk about the negative fallout of all of these, shall we say, hateful statements?" he said. "What credibility will the government have to address racism and xenophobia and any other negative consequence of these statements?"

As for Russell, the Quebec-born singer now lives in Nashville with her family and recently, after playing in well-known American folk bands, began a solo career with her album Outside Child.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies