Did an African royal really attend Shaw? The true story of Prince Alfred Impey.

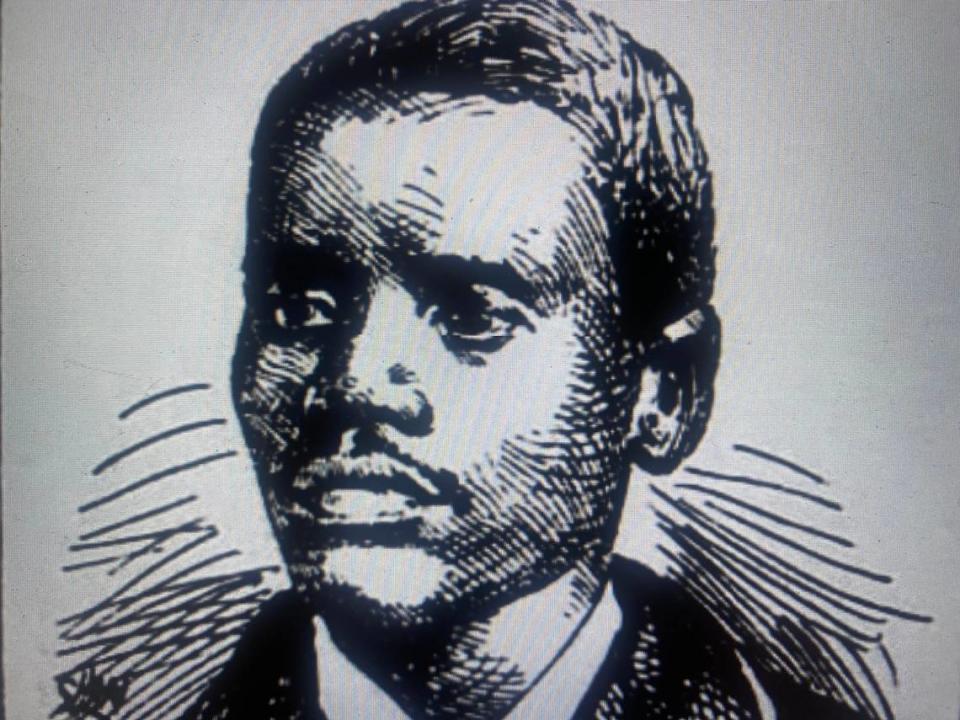

He was only 19, and his journey to Raleigh took three days on horseback, three more by train, then fourteen more by steamship — much of that time spent shivering.

But in 1897, Prince Alfred Impey found himself enrolled at Shaw University, making him perhaps the first African royal to study in America. He offered this first impression of his adopted home while huddling under an overcoat in the football stands:

“I suffer from the cold here,” he told an interviewer. “It is not cold in my country.”

The young prince’s story ranks among Raleigh’s most forgotten mostly because the prince contracted tuberculosis almost immediately after arriving.

Though he was grandson to William Kama, the celebrated Xhosa chief in South Africa, the prince got shuttled off to a hospital in Southern Pines meant for Black patients only, where he wasted slowly away, writing letters to Shaw seeking money for pencil erasers and hair oil.

When he died alone in the Pickford Sanitarium, the news made headlines in almost every newspaper from here to California — except, predictably, The News & Observer, which was run at the time by white supremacist Josephus Daniels.

So l’m fixing that omission now.

I’d like to offer some long-overdue fanfare for a kid of noble birth, second-in-line to the chiefdom in his homeland, who traveled 8,000 miles for an education so he could come back to Africa as a doctor and minister — only to find sickness abroad.

It makes for a bleak but fascinating story.

He did not ‘wish to be king’

“My name is Alfred Impey,” he told his interviewer, a correspondent for The Evening Star in Washington, D.C. “I do not wish to be king.”

I stumbled on the prince’s life while poking through old newspapers on the trail of Nicholas Franklin Roberts, who was once the dean of Shaw’s Divinity School, and whose academic feats in the late 1800s earned him an NC historic marker just last week.

Roberts acted as Impey’s Raleigh caretaker, and he raved thusly to the Evening Star: “His habits are industrious and his deportment perfect. He looks forward to the day when he will return to Africa to elevate and instruct his own people.”

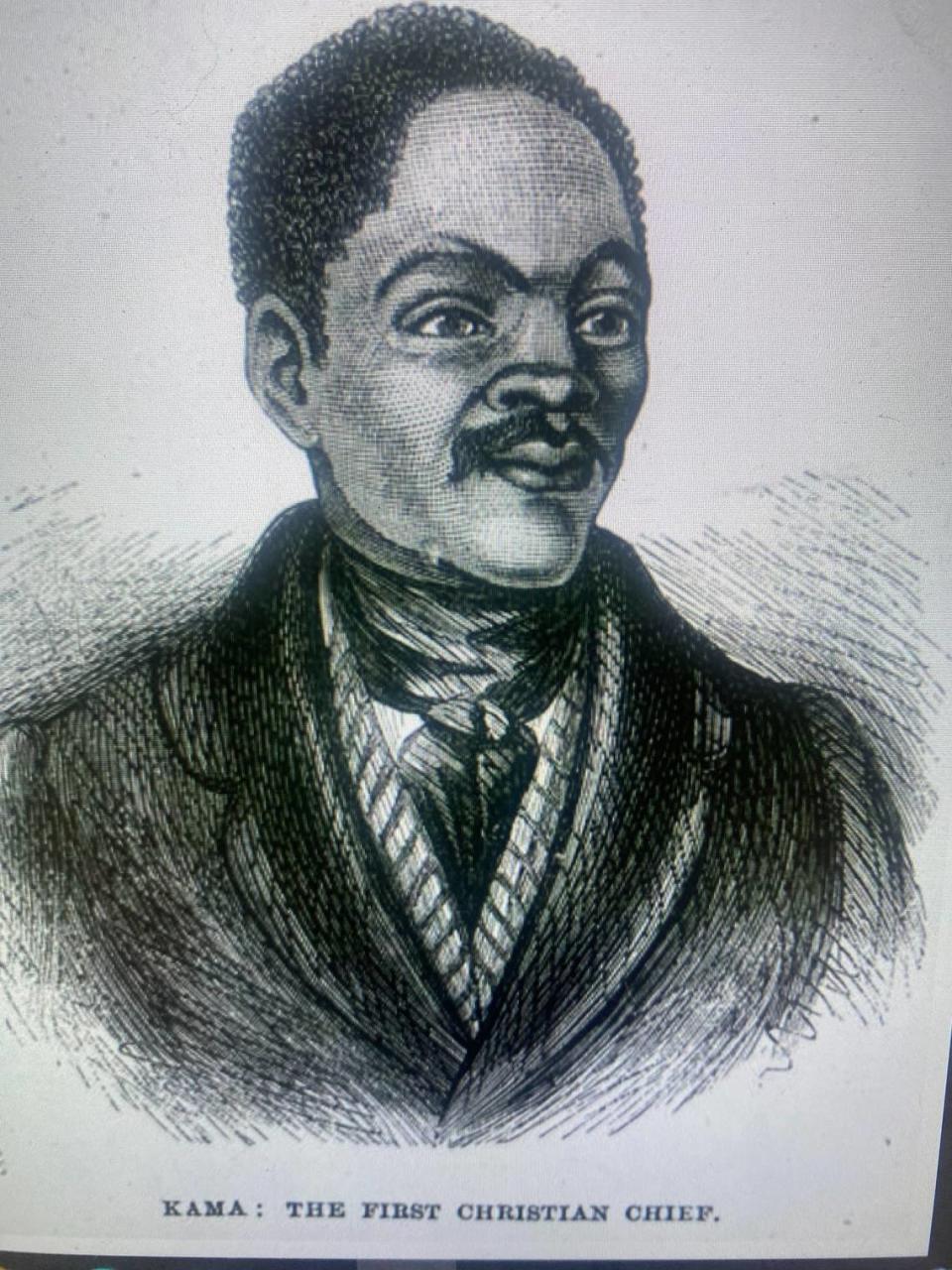

But the prince’s people were already fairly elevated, mainly because Chief Kama was the first and only leader from his branch of the Xhosa to accept Christianity.

With help from UNC-Chapel Hill history professor Lauren Jarvis, I tracked down accounts of Kama’s tearful turning-away from what Methodists of the day called “dense spiritual darkness” and “revolting vices.”

That history recounts Kama witnessing communion and baptism in 1824, and, “although not understanding our language, he had been seized with an apparently irresistible emotion, and shed ‘floods of tears.’”

Kama cooperated with the British occupying what was then the Cape Colony and fathered three sons, two of whom died young from what the Methodists described as the “terrible scourge” of Cape Brandy.

The “old chief” was popular enough to draw 800 mourners to his funeral, but Prince Alfred, whose father had already expired from colonial brandy, looked to missionaries for his upbringing, English and baptism.

Alfred Impey never knew his uncle as anything other than “King William,” and by the time the young prince reached Raleigh, his grandfather’s successor had grown gray in the beard. He mentioned his royal connections in the breath he spent talking about his fandom for cricket and tennis — which he played at Shaw.

“The British give him an allowance,” he told The Evening Star, describing his noble uncle. “His house is a great one, like the one we are now in, made of stone and brick.”

A sad end for the prince

But now we come to the prince’s sad end.

A few weeks after his interview at the “foot ball” game, Alfred Impey took sick and headed to Southern Pines, where a new sanitarium had just been built — the only facility set aside to treat TB among Blacks in the South. It housed about two dozen and charged $12 a month.

After I emailed last week, university archivist Marie Stark tracked down a heartbreaking string of letters between the prince and Charles Francis Meserve, who was then Shaw’s president. He wrote, “I stand in place of a father to you,” and “You will surely be remembered in our prayers.”

Meserve made several visits to Southern Pines, though tuberculosis was wildly contagious at the time and antibiotics stood decades in the future. He delivered pairs of woolly underwear and sat reading the Bible with his sickly student.

In a letter to some Methodist missionaries, Meserve described joking with the young prince during recuperation, asking him whether any his people back home used “intoxicants.”

Some do, the prince replied.

What about King Kama? the president asked. And the prince turned cross.

“He looked up in a way that seemed to indicate that he was well-nigh offended,” Shaw’s president wrote, “and very emphatically replied, ‘No King Kama is a Christian.’ I thought this reply, coming from one who had only just left his African surroundings, was a severe commentary on our boasted civilization.”

He added this note about the prince’s interactions in rural North Carolina:

“He does not seem to take kindly to white people that he meets.”

A few days later, Prince Alfred Impey was dead — a news item that made headlines in St. Louis, New Orleans and Los Angeles. When it noted his passing, The Evening Star recalled its old football interview.

“He was not robust,” it read. “Winter affected him greatly.”

If only North Carolina’s weather, and its people, had been warmer.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies