How a diary from a Vietnamese battlefield brought two lives together, 50 years later

Peter Mathews came from the Netherlands and moved to the United States in the 1960s. He has a construction business, gray hair and blue eyes.

Cao Van Tuat grew up in a small village near the coast of Vietnam. His family farmed and caught fish for a living. To our knowledge, no photograph of him exists.

The two lives seem very far apart, but only until you look more closely.

You can read all about who these two men are, and how their paths crossed, in "The book from the enemy," a story we published this week at USA TODAY. It was written by my colleague Megan Burrow in New Jersey and correspondent Nhung Nguyen in Vietnam.

'The book from the enemy': A lifetime after Vietnam, U.S. veteran delivers a diary to its home

Megan writes about “anything and everything that happens in Bergen County,” so when Mathews called his local newspaper with an unusual tale, of course, the voicemail found its way to her.

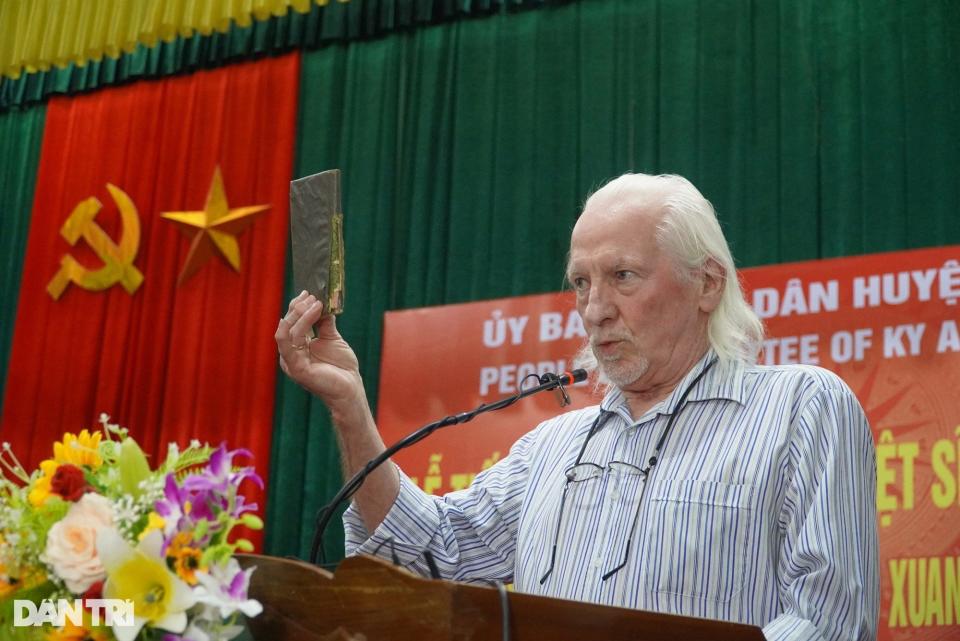

Megan interviewed him and wrote a story in January about how Mathews, more than 50 years after fighting in Vietnam, still had a diary from a North Vietnamese soldier. He had found the notebook on the battlefield during one of the bloodiest battles of the war. Some people who had seen it called it “the book from the enemy.”

But Mathews wanted to figure out who the author was and give it back.

“That was his goal,” Megan says, “but it was kind of like his dream.”

A story within a story: Journey back to Vietnam

They both had a sense that finding the author was unlikely. Instead, it only took a couple of days.

Megan’s story for northjersey.com, part of the USA TODAY Network, launched a chain of events that would have been a story unto itself: Officials in Vietnam, working with a researcher in Alaska, had a lawyer visiting Mathews in New Jersey and officials visiting surprised relatives in a tiny village called Cao Thang. Soon, they had confirmed the identity of the soldier, notified the family and set up an international journey for Mathews to return the diary to its home.

“The whole thing was amazing,” Megan says. “He would text me updates: ‘Now this person in Vietnam is wanting to interview me.’ ‘Now Vietnam Airlines is offering plane tickets.’ He was so excited about it, and it was moving so quickly.”

As that trip arrived, I talked with Megan and her editors about covering that part of the story. By then, we knew quite a bit about Mathews. How he had been an immigrant to the U.S. when he was drafted and sent to Vietnam, how he had been awed by the beauty of this diary, and how he had struggled with life at home even after surviving the war.

But we knew almost nothing about the man who had written it: Cao Van Tuat.

Reporter Nhung Nguyen, who is based in Ho Chi Minh City, was determined to find out more. In early March, we asked Nhung to travel to the rural coastline where Tuat had grown up, to be there when Mathews arrived to hand over the diary to Tuat’s nephew and sisters, his surviving relatives.

Nhung knew the event, produced by government officials, would be heavy on formalities. She wanted to know more.

Soon, she was sitting in a three-room house in a tiny village called Cao Thang, drinking tea with Tuat’s nephew before the TV cameras arrived, and learning all about the man who wrote the diary: How he had disliked his ordinary middle name and had changed it to Xuan, meaning “spring.” How he had joined the army when he was 21. How he had a girlfriend and wanted to ask her family for her hand in marriage when he returned from the war. How he had sent home only one letter.

His family waited nine years to receive his death certificate, Tuat’s nephew said. They didn’t know where he fought or when he died. They didn’t even have a photograph of him.

But now, there would be a diary, full of drawings and calligraphy, and verses, including one Tuat’s nephew read aloud:

I am away from you, missing you a thousand times … I could feel you are waiting for me in the middle of this cold night … Don’t yearn for my return.

“It was like Tuat knew his fate,” Nhung says.

'They don't share the same language (but) share the same soul'

We published Megan and Nhung’s story this week, just as Vietnam War veterans in the U.S. were gathering to mark the 50th anniversary of the withdrawal of American combat troops from South Vietnam.

The war remains as complex and controversial today as it was in 1967 when a young Army sergeant found a beautiful notebook on the ground at Dak To. But when both Megan and Nhung looked at the story of Peter Mathews and Cao Van Tuat’s diary, that isn’t what they saw.

Instead, they saw the similarities. Two men who had both left their homes in 1963. Two men who had been on the same battlefield in 1967. Two men who had an eye for beautiful drawings in a notebook.

“The fact that he appreciated the drawings and calligraphy,” Megan says, “I think he has this artistic view that they kind of share.”

It’s hard for us to know how Tuat would have felt about the American soldiers he was fighting.

Megan thinks he may have been more devoted to his cause than Mathews was to his. “He didn’t volunteer to go, he was drafted,” she says. “He was just there. I think he never saw them as the enemy, exactly.”

Nhung sees a beautiful diary – full of trauma, characters, feelings – one that belonged to Mathews in as many ways as it did to Tuat.

“Following this story for a week, I just saw two young men who were put in the wrong positions at the wrong time,” she says. “The men from two sides who kill each other, they don’t share the same language, but they actually share the same soul. Whatever wars have taught us, we are not so different.”

Josh Susong is senior editor for storytelling and enterprise at USA TODAY.

The Backstory offers insights into our biggest stories of the week. If you'd like to get The Backstory in your inbox, sign up here. Subscribe to USA TODAY here.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How a Vietnam War veteran returned a Vietnamese diary 50 years later

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies