Feds are tracking Americans' social media to identify dangerous conspiracies. Critics worry for civil liberties.

Since 2018, at least three white supremacist mass shooters in America have referred to the “Great Replacement” theory, a conspiracy claim that white people are being replaced in the U.S. and elsewhere by immigrants of color.

That’s the narrative Robert Bowers alluded to on social media before killing 11 people at a synagogue in Pittsburgh in 2018. Patrick Crusius, who killed 22 people at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, less than a year later, was inspired by the racist trope. So was John Earnest, who killed one person and injured three in a shooting in Poway, California.

Had federal law enforcement agencies known this conspiracy theory was spreading fast on social media, they might have been better able to prepare for these attacks, and perhaps even stave them off.

At least, that's the argument made by senior Department of Homeland Security officials who outlined a new effort to analyze public social media posts with the aim of better understanding extremist narratives and movements.

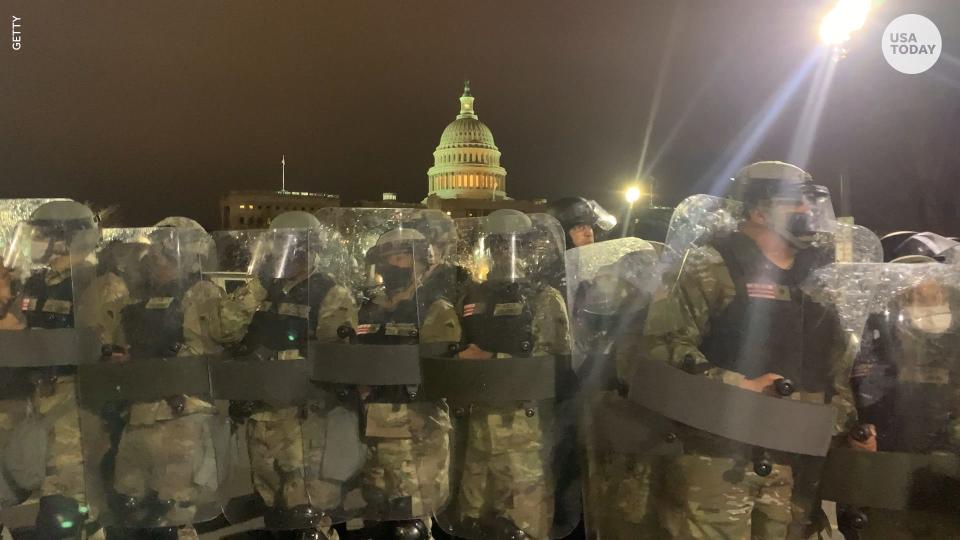

The effort – which draws from research conducted by nonprofits, academia and the department itself – aims to identify narratives and campaigns that could lead to domestic terrorist attacks or violent incidents like the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

Officials stressed that the goal is not to monitor specific individuals or chill free speech, but rather to build an early warning system for dangerous events.

"This is so we can have a greater understanding of the threat environment as it evolves and then think through what steps we can take, working with state and local authorities and community groups to mitigate the risk posed by those threats," a senior Homeland Security official said in an interview. The officials spoke on condition of anonymity in order to freely discuss the program.

Extremist fundraising: Capitol riot extremists, Trump supporters raise money for lawyer bills online

But extremism experts, academics and former Homeland Security officials question how much is actually new about the effort and raised concerns about the specter of a massive federal security agency gathering information about U.S. citizens.

They pointed out that domestic terrorists don't plan their attacks on public-facing social media and questioned whether monitoring movements online can be effective without identifying individuals. And they worry the Department of Homeland Security might engage public sector "experts" to monitor domestic extremism who don't have the expertise needed for such complicated work.

"This effort could provide a clue about something thematically – sort of a mood or a sentiment that is out there – but for the most part, it's not going to point you in the direction of specific plots," said Javed Ali, senior director for counterterrorism at the National Security Council in 2017 and 2018.

"I saw the results of this cottage industry explosion post-9/11 when everyone was an international terrorism expert," he said, "and if we're not careful, we're going to do the same dumb thing on domestic terrorism."

Watching extremist narratives evolve online

The government's approach to analyzing social media posts will focus less on trying to find a person who might commit domestic terrorism and more on the narratives and themes that are setting online communities alight, the DHS officials said.

The Homeland Security officials said a new working group will assess which nonprofit and academic resources can be used to understand themes like the Great Replacement theory and how the department can use that information, and its own intelligence gathering, to stave off attacks.

The social media monitoring idea is part of a reorientation by the federal security agency to focus on domestic terrorism in the wake of the Jan. 6 insurrection and after years of increased violence by white supremacists and other homegrown extremists. The department also announced the creation of a domestic terrorism branch within its Office of Intelligence & Analysis.

While Ali applauded any effort to boost the fight against domestic extremism, he pointed out that these efforts are essentially a return to work that largely foundered during the Trump administration.

"They're just kind of dusting off something that has existed in various periods and iterations," Ali said. "It's not necessarily new, it's more kickstarting older efforts."

Conspiracy: Capitol riot spurred conspiracy charge against 31 suspects, but how hard is it to prove?

Concerns about civil liberties

The department's plans to use social media to predict violent incidents are still in their infancy, and officials have been tight-lipped about exactly what information they will gather, whether and how they will store it, and how it might be shared.

That concerns extremism experts and civil liberties organizations.

"The proof for this is in the pudding," said Heidi Beirich, chief strategy officer of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism. "I want the details: What information do you keep? How long do you keep it? Who gets to see it?"

Sweeping up vast amounts of social media information will undoubtedly result in identifying individuals who are threatening violence, Beirich said.

"They say they're not going to use names, and they're just going to look at trends," Beirich said. "They say they aren't going to have identifiers, but anybody who has studied this long enough knows there's always information in there that points you to who a person is."

Sarah Peck, a Homeland Security spokeswoman, said the department is mindful of those issues.

"All of our efforts are carried out in close coordination with our privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties experts and consistent with the law,” she said in a written statement.

The American Civil Liberties Union called the creation of the new Homeland Security center to address domestic extremism deeply concerning.

"Of course, we all want to address white supremacist violence effectively, but these efforts appear to be no different than earlier failed, discriminatory programs and could continue the same harmful cycle we have seen for years now after promises of doing better,” Manar Waheed, ACLU senior legislative and advocacy counsel, said in a written statement.

A small pool of experts

Beirich, Ali and several other experts on domestic extremism said one of the biggest challenges Homeland Security officials face in monitoring social media is finding experts who understand domestic extremism and are willing to work with the U.S. government.

"There are very few real experts," said Megan Squire, a computer science professor at Elon University who studies extremism. "And there will be wariness and skepticism from those experts."

Without proper guidance, Homeland Security risks not just overstepping its role in keeping Americans safe, but focusing on issues, trends and narratives that don't actually pose a threat, Beirich said.

That's what happened after 9/11, when Muslim communities in the U.S. found themselves under illegal surveillance from law enforcement, and dozens of foreign nationals were arrested and imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay for more than a decade without being charged with a crime.

"The government is going to have to forge some good relationships with experts so that they don't make mistakes like they made after 9/11," Beirich said. "I worry about all of that."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Homeland Security tracking social media to track domestic terrorism

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies