Dempsey v Carpentier July 1921: the start of modern sports broadcasting

“Carpentier is out … Jack Dempsey is still the heavyweight champion of the world.”

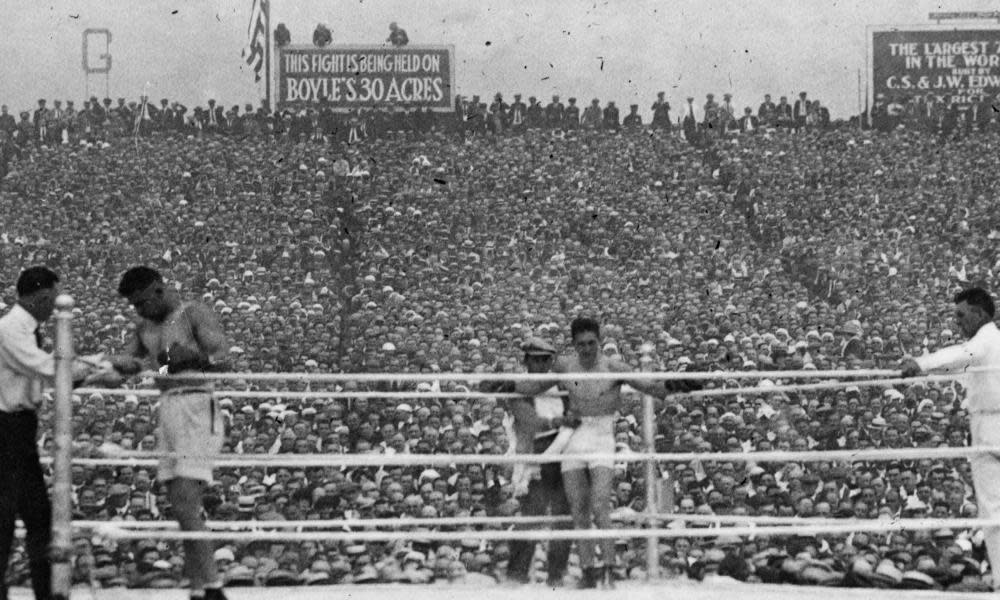

It was Saturday 2 July 1921, a boiling summer afternoon in a field on the outskirts of Jersey City, and a raucous crowd of more than 80,000 had just witnessed what had been billed as the fight of the century.

The stylish French challenger Georges Carpentier, the world light-heavyweight champion, lay in the middle of the ring, a broken, twitching heap after being battered for nearly four rounds by one of the most ferocious fighters who lived.

The crowd was the largest, the purses paid to the fighters the fattest and the gate receipts topped $1.5m – the first time a sporting gate had hit seven figures. But that wasn’t the biggest story of the day.

At ringside, Major J Andrew White, plain Andy to his friends, put down his telephone and sank back into his seat exhausted. He’d been talking for more than four hours. He’d just completed the first major live sports broadcast on the radio and his first thought was to find out how it had gone. He dialled the office, but all he got was a deafening silence. The line was dead. But how long had it been dead?

“There I was. For four hours, I had talked steadily under that hot sun, in the fight arena dust, giving the best that was in me,” White said. “And now when I tried to find out the results of my work, the line was dead.”

He tried over and over again, until finally the line clicked through. “What was the last thing you heard?” he said, breathlessly.

As the vast crowd streamed happily toward the exits, not one of them understood the real significance of what had just happened. The fight would go down in boxing folklore. What has been largely forgotten over the past 100 years is that almost overnight it created two brand new multibillion-dollar industries.

White, a nattily dressed 32‑year‑old New Yorker with a passion for amateur radio, had hoped his words would herald a new media era, proving beyond all doubt that his beloved radio could be broadcast across the country and bring big events into every American home. His was the first proper sports commentary. And it launched the age of sports rights.

***

The story began in the tiny Broadway offices of the National Wireless Association with a plan to broadcast the fight and raise money for a veterans charity run by the philanthropic socialite Anne Morgan, daughter of the financier JP Morgan. Promoter Tex Rickard, keen to oil his relationship with the Morgans, saw no value in radio and agreed to the broadcast. White was the NAWA’s president and he jumped at the chance to take on the job, even though few Americans had radio receivers and potential investors saw it as an experimental, passing fancy.

The fight was also a dream ticket for a creative and theatrical promoter such as Rickard – pitching the handsome, French sophisticate Carpentier, a decorated first world war flying ace against the uneducated, street fighter Dempsey, who had been accused of dodging the draft. Rickard just needed to find a place big enough to put on the show.

White estimated the cost of the radio broadcast was about $15,000 and had confidently set about raising it, but everyone he tried told him he was crazy and showed him the door. His last chance was a meeting with an old friend at RCA, another young radio enthusiast called David Sarnoff, who had proposed the pioneering idea of transmitting music on radio into people’s homes as early as 1916. It was rejected as science fiction.

Sarnoff had only $1500 but offered to help White make it happen. The team targeted the longwave frequency of 1600 meters, which was owned by the US Navy, but White persuaded them to play ball. A special licence was granted by the government to allow a temporary 24-hour radio “station” to be created for the broadcast. It would be called WJY. All they needed now was a base in which to put it all, a transmitter powerful enough to generate the signal for 200 miles in all directions and a tower tall enough to send it from.

White had heard of a powerful transmitter in Schenectady, in upstate New York, which had been built for the navy by the General Electric Company. White met the Navy Club’s president, Franklin D Roosevelt, and asked if it was possible to borrow the giant 3.5-kilowatt transmitter, which was the size of a telephone box. The future president, a keen boxing fan and amateur radio enthusiast, agreed and White hired a barge to move the transmitter 160 miles down the Hudson River to Hoboken, where it was connected to a vast antenna that was strung from a nearby 450-foot transmission tower to the clock tower of the railroad station.

The team sent out 7,500 letters and forms to every radio enthusiast in the eastern states asking for their help. By the middle of June, 58 theatres and halls had been secured. In addition, the army of enthusiasts were rigging up their loudspeakers in streets, schools, fire stations, even their own front yards.

The army of enthusiasts were rigging up loudspeakers in streets, schools, fire stations, even their own front yards.

On Friday 24 June, with the 2,000 DC motor generator humming sweetly outside, they turned the system to full power for the first time and thanked their 100-plus army of mini radio stations by name. So many calls came back that they had to take over the local switchboard to handle them.

They’d done it. Surely nothing could stop them now? But less than 24 hours before the fight a telegraph arrived in their Hoboken office. White took a deep breath. “Gentleman, I think that just about does it. AT&T won’t allow us to connect our ringside position with the telephone network.”

AT&T were RCA’s biggest rivals in the race for dominance in the radio business and didn’t want them to steal a march by broadcasting the fight. Their official reason was their concerns over the lack of security around a radio network of such scale being connected to the telephone network, but that was just a smokescreen. Then White had a brilliant idea. They would bypass the phone network by running a cable 2.5 miles from ringside to their transmitter, in effect their own private phone line.

“AT&T can’t stop us connecting to their network from here,” he said. “We’ve got a government licence to operate a radio station for 24 hours.”

White’s plan was to commentate from ringside and a high-speed telegraph operator in Hoboken would type it out and one of the engineers would read it to the network. “We’ll even get a gong to bang in here to start and finish the rounds,” he said. “It’ll only be a minute or so late, but nobody will be quicker than us. And nobody will know the difference.”

***

Fight day dawned under grey skies and there were queues outside snaking around the freshly built stadium for miles. Just before 3pm the band struck up La Marseillaise and the whole arena seemed to move as the crowd roared its approval for Carpentier, as the Frenchman, wearing a big smile and a dove grey kimono, climbed into the ring and waved.

Dempsey got the last laugh, taking the best the Frenchman could throw at him and in the fourth round planting his opponent on the canvas with a furious barrage of blows, then following it up with a heavy shot straight to the heart. Carpentier folded sideways to the deck.

White’s commentary was over. Now he wanted to know if all the hard work had paid off. When he eventually got through to Hoboken, he said: “What was the last thing you heard?”

“Dempsey is still heavyweight champion of the world,” came the reply.

They had got it all, despite a battery on the telephone line dying at the end of the broadcast and a transmitter tube blowing halfway through. Broadcast over more than 250 miles, more than 350,000 people had listened to the fight – the biggest radio audience in history. The biggest audience of anything in history.

“Then came a stream of telegrams and more than 4,000 letters,” said White. “The receiving operators were wildly enthusiastic; they had heard everything. Functioning indifferently well, the loudspeakers had brought the blow-by-blow account clearly to the auditoriums. The crowds who heard the radio descriptions knew the outcome sooner than those who had depended on any other means of communication. The first time radio had been used for news, it had justified itself.”

It might not have been White’s voice that had been heard across the eastern states, but it was his words. But no one outside their own little circle knew the trick they had played and overnight White became something of a celebrity. He had created an entirely new profession. The success encouraged RCA to apply for the company’s first permanent broadcast licence and it would become the New York-based WJZ – one of the most important stations in the country.

The radio craze was born. Stations began to appear in every town and city across the States and the demand for radio sets skyrocketed. Within months, a diet of music, news and sport became the big attraction on radio and the sale of advertising became a huge growth industry. The annual sale of radio sets rose from $60m in 1922 to $358m in 1924.

As the years went by White faded from view. His death, in the mid-60s, did not merit a single newspaper line. The visionary Sarnoff, however, leveraged the fight’s success and built RCA into one of the world’s most powerful broadcast forces. He would become the father of modern broadcasting, launching NBC television in 1939 and pioneering colour TV in the 60s.

For their imagination, courage, entrepreneurial spirit and plain stubbornness, today’s sports multibillion dollar broadcasting world owes them an enormous debt.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies