Democrats can shore up democracy or attack SCOTUS — not both

President Biden has come under deserved criticism for his suggestion at his press conference Wednesday that the midterm elections might not be legitimate if the Democrats' voting rights and other election reform bills aren't passed before then. Comparisons to former President Donald Trump's declaration, in advance of both the 2016 and 2020 elections, that if he lost it would be a sign that the election was stolen may seem excessive, but they're not all that inapropos.

But while voting rights legislation is currently stalled because of moderate Democratic opposition to altering the filibuster, there's another, more pressing reform gathering bipartisan support in Congress that could do a great deal to shore up public confidence in the legitimacy of our elections. That reform would require the courts to exercise greater election supervision — and, unfortunately, some Democrats have been busy undermining their legitimacy as well. If they keep doing that, they'll undo much of the good that reform could achieve.

Republican efforts in a number of states to limit the availability of absentee ballots and complicate in-person voting are pernicious, but they are familiar, and their impact is limited by the serious get-out-the-vote effort that the Democrats are certain to launch. Indeed, there's little evidence that either liberalizing or restricting access to the ballot materially impacts either turnout or election outcomes.

By contrast, Republican efforts to involve partisan legislatures more directly in the conduct of elections and the vote count raises the specter of a genuinely illegitimate result. Even if GOP state lawmakers behave honorably, partisan distrust is not at all unreasonable, and the prospect of Democratic refusal to accept an election's results should worry anyone who cares about democracy — just as Republican refusal to accept the 2020 results does now.

An effective reform of the Electoral Count Act would address this problem head-on. Properly designed, it would remove any lingering responsibility in Congress for resolving disputes about slates of electors, and it would also prevent state legislatures from interfering with the election count or removing election officials without cause. A number of Senate Republicans seem amenable to such reform precisely because they don't want the responsibility for either standing up to Trump or knuckling under if the events of 2020 repeat themselves.

Such a reform, though, would require the courts — federal courts, since reform legislation would nationalize many of these questions — to decide any disputes that might arise. Courts would rule whether a state legislature had improperly removed a county-level elections supervisor, whether ballots were being rejected in an ad hoc manner with partisan intent, or even which slate of electors to accept in the event that we see a repeat of 1876. The legitimacy of a disputed election in the eyes of the public, then, would depend on the legitimacy of the federal courts and, ultimately, the Supreme Court.

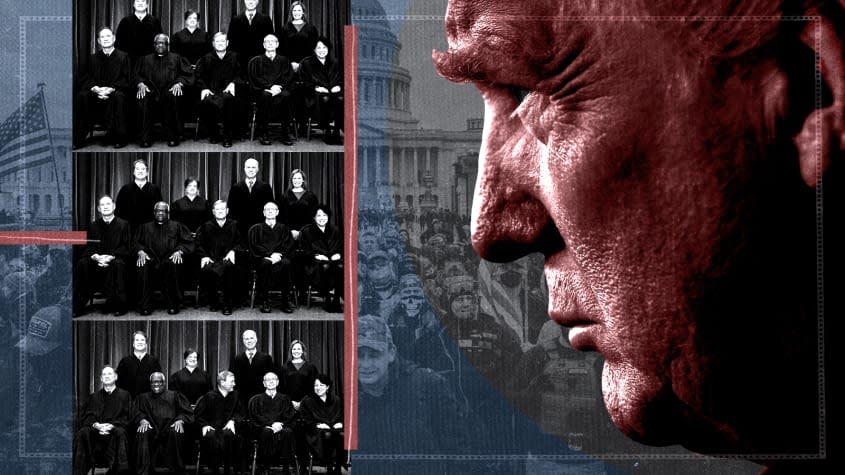

And there's the problem. Ever since the 2000 presidential election was only resolved with Bush v. Gore, many Democrats have viewed the Supreme Court through an increasingly partisan and not merely an ideological lens. The see Republican-appointed justices as doing the bidding of their appointer's party rather than merely following an judicial ideology with which Democrats disagree. Now that the court has a 6-3 conservative majority that includes three Trump appointees, the impulse to question the Court's legitimacy has grown far stronger.

To be sure, there's a strong philosophical argument to be made that liberal reliance on the courts is ultimately counterproductive. Rights, like any other public good in a democracy, ultimately depend on a popular majority to sustain their support. The court's proper job is to ensure they are protected equitably, and not in a way that leaves disfavored minorities in the cold. By contrast, a court eager to overrule the elected branches is unlikely to be helpful to progressive ends, even if it isn't tyrannous.

But it is emphatically the role of the court to adjudicate between branches and levels of government, to ensure that the rules of the political game are properly followed. To do that job effectively, the court must be seen at least to be striving to sit above partisanship.

Is it, though? Well, consider that mere hours after Biden's election legitimacy comment, an 8-1 majority ruled against Trump on the politically-sensitive matter of White House records related to the Jan. 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol. All three Trump appointees were in the majority.

The ruling is particularly interesting because Justice Brett Kavanaugh has historically held a broad view of executive privilege, and many suspected he had been chosen by Trump over more committed abortion opponents precisely because of that fact. Yet Kavanaugh joined the majority.

He also joined the majority in both recent cases regarding vaccine mandates, upholding the mandate on health-care workers at facilities receiving Medicare and Medicaid funds while rejecting the broader OSHA requirement for large companies to mandate vaccination or regularly test their employees.

Either decision may be criticized, but in the context of state-level action that has been overwhelmingly less aggressive in imposing mandates, and in the absence of any enabling legislation, it's far from clear that the latter decision overruled the will of the people.

Democrats need to not only notice this, but to take note of it publicly. If they want to use the courts to help restore confidence in the legitimacy of our elections, they need to encourage confidence in the legitimacy of the courts themselves, rather than undermine it by decrying them as partisan or, worse, indulging in fantasies of court packing that would utterly destroy it.

Upholding the legitimacy of the courts is perfectly compatible with aiming to limit their role. Much of the substance of the voting rights bills rebukes earlier Supreme Court decisions on campaign finance, on the Voting Rights Act, and so forth. The way you rebuke a bad decision is with good legislation — and the Democrats have the power to pass any legislation they wish, if they choose to use it.

What they can't do is guarantee that the arbiters of our election rules always decide in their favor. They can only decide, along with Republicans, who those arbiters will be, then build up public trust in their fairness.

You may also like

California deputy DA opposed to vaccine mandates dies of COVID-19

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies