Delta is the 'most serious' COVID-19 variant, scientists say. How will it affect the US?

As the Delta variant of COVID-19 tore through India last month, there was a lot of concern, but few answers about what would happen when it arrived in the United States.

Now that it accounts for at least 6% of this country's infections, there are a few more answers.

But it's still unclear whether Delta will go the mostly harmless way of other variants – or pose a serious threat to people who choose to skip COVID-19 shots.

"Globally, Delta is the most serious development that we know of in terms of the evolution of the virus," said William Hanage, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The real danger, if any, will be to people who have chosen not to get vaccinated, he and others said.

"Until a few weeks ago, I would have said they're probably going to get away with (being unvaccinated)," said Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. But "if Delta really takes off, that choice looks worse and worse."

Vaccinated people should remain safe, he and others said. Even if they do get infected, they're likely to get a mild case of COVID-19.

But Wachter said a few new facts have made him worried about Delta's impact on unvaccinated Americans.

First, he's now convinced that Delta will take over as the main cause of COVID-19 in the U.S. because it's more contagious than previous variants.

It's still unclear whether Delta is also more dangerous, but early data can't rule that out, and on Tuesday the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention upgraded Delta to "a variant of concern," a more serious category than it had been in before.

With a virus that is more contagious, a larger percentage of the population needs to be protected through vaccination or natural infection to keep the virus from spreading.

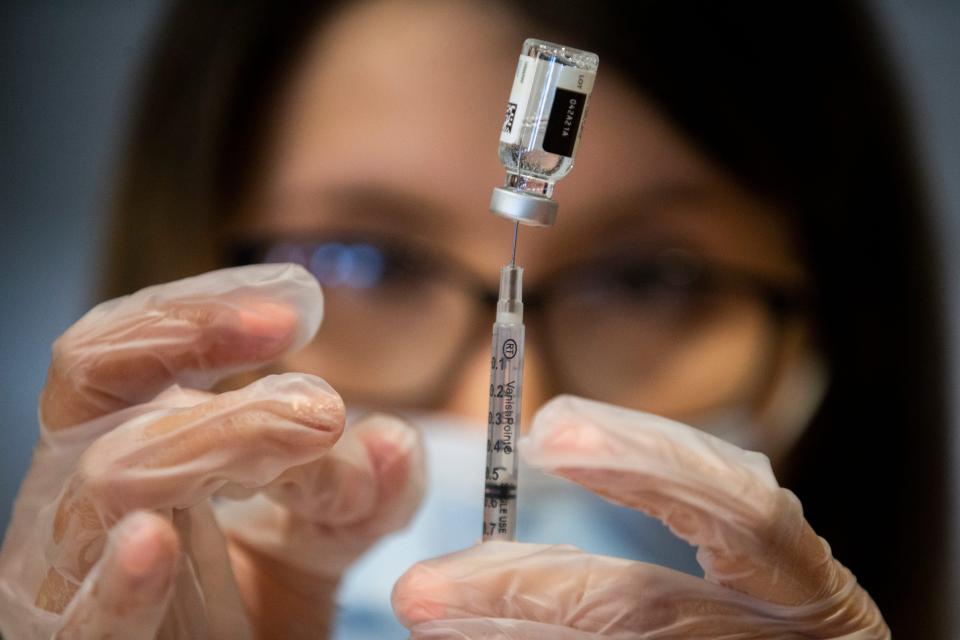

A new study shows that vaccinated people are safe against the Delta variant – but only after they get a second dose, meaning it'll take a minimum of five or six weeks between the time someone decides to get vaccinated and when they're protected. So anyone who changes their mind after cases start rising probably won't have time to get protected, said Wachter, who laid out his concerns in a recent Twitter thread.

And he's concerned about what will happen to the unvaccinated in the fall, when cases are expected to climb, as flu does, with the season.

"Two weeks ago," he said, he would have predicted minor surges in the fall and the winter. "I'm now much more worried about Michigan-type surges."

More: What is the new coronavirus Delta variant, and should Americans be worried?

Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, shares his concern.

"When people choose not to be vaccinated, they're essentially contributing to an unfortunate natural experiment" to see what Delta will do, Offit said.

Although COVID-19 cases are way down in the United States – more than 90% since January – there is still enough virus circulating to cause a resurgence with just a small push, like the change of seasons, Offit said. "This is a winter virus at its heart."

Think of protection as a line, Wachter said. The more protected you are, the further you are over the line.

Two shots probably push people further past the line than a mild case of disease. People who are immunocompromised because of age or a medical condition don't get as far. And as immunity wanes over time, everyone gets closer to that dividing line.

On the opposite side, a variant like Delta moves the line, making it harder to get and stay protected, Wachter said.

His message to the unvaccinated: "You are less safe than you think you are and less safe than we would have thought two weeks ago now that we're understanding what's going on with Delta."

Message from abroad: UK cases are climbing

In the United Kingdom, where vaccination rates are similar to the U.S.'s, cases are climbing by 64% per week and are doubling each week in the country's hot spots, according to the BBC. On Monday, U.K. prime minister Boris Johnson delayed his country's planned reopening until July 19 to allow more people to get fully vaccinated.

Also Monday, Public Health England said the Pfizer-BioNTech and AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccines performed just as well against the Delta variant after two doses as against the original strain, with both more than 90% effective.

Some worry that the United States may be just a few weeks behind the U.K.

Hanage said the U.S. is so big and diverse that different areas are likely to see different outbreaks.

"I don't think we're going to get a national surge," he said. "Countrywide, the number of vaccinations are going to be hard for Delta to evade."

An area with 90% vaccination may be safe, and not see any outbreak at all, he said. Unless the 10% who are unvaccinated "all work in the same meatpacking plant," in which case that could spur a serious local problem.

As at the beginning of the pandemic, he said, areas with low vaccination rates will either get lucky – and avoid a super-spreading event – or they'll get unlucky and face a devastating outbreak.

Thanksgiving, he said, when families travel to spend time together, could spread the misfortune.

The fact that this variant seems more transmissible means it's more able to cause explosive outbreaks, Hanage said, "and get into people before we are able to get a shot into them."

More: WHO renames COVID-19 variants with Greek letter names to avoid confusion, stigma

Hoping for the best

Theodora Hatziioannou, a virologist at Rockefeller University in New York, has been helping track 140 people since they were infected with COVID-19 early in the pandemic. She and her colleagues have studied the volunteers at two months after infection, six months and now a year.

The longer out they are from their infection, the more protective antibodies they have, the team's new study shows.

"Apparently, you need several months up to a year to get these really really good antibodies," she said.

When people who had COVID-19 get vaccinated, they are even better protected.

"You already had good memory B cells in your body" from the infection, Hatziioannou said. "All you need is something to tickle them and tell them to wake up and start producing antibodies."

Seeing the body's response to natural infection and vaccination put Hatziioannou among the "small minority" of virologists not concerned about the Delta variant. "Everybody's panicking about every variant being more transmissible and I don't buy it," she said. There are other reasons to explain why those variants have taken off and appear more dangerous than the original strain.

She's more concerned, she said, about half-vaccinations and what might happen if the virus is allowed to surge again in a population that's only partially protected. That might drive the virus to mutate to avoid being thwarted by vaccines.

"It's very important to keep the virus at bay until everybody is fully vaccinated. One dose is not sufficient," she said.

The bottom line: If everyone was vaccinated, no one would need to worry about the variants.

"But if we continue allowing this virus to spread, eventually, we will have a variant we have to worry about," Hatziioannou said. "That's the issue."

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Delta variant: How will it affect US cases, vaccine efficacy?

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies