'I was deceived': NFL players raise questions about Prolanthropy, group that managed their nonprofits

When Charles “Peanut” Tillman was named the 2013 Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year, websites for the league and his team, the Chicago Bears, reported his Cornerstone Foundation had distributed more than $1 million to at-risk families through its “Tiana Fund.”

But the Cornerstone Foundation’s first five years of federal tax records show the nonprofit had disbursed $797,000 in total charity and $327,000 through its Tiana Fund to that point.

Tillman told The USA TODAY Network he didn’t realize the financial impact of the Cornerstone Foundation had been embellished.

But early in his relationship with Prolanthropy, the management company hired to run his nonprofit, he suspected it was exaggerating the organization’s achievements and said he confronted its CEO and founder, Jeff Ginn.

“I remember I called him out on something where it said I helped a million kids,” Tillman said. “I was like, ‘How did I help a million? We helped a million people already? I think I’m good, but dang, that’s a lot of people.’”

Tillman, now retired from the NFL, said he left Prolanthropy after the company took a cut of the prize money he received for winning the Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year award. His foundation, which reported record revenues and expenses in 2014, spent just 26 cents of every dollar on charitable activities that year, its last under Prolanthropy management.

Tillman said he refused to sign a nondisclosure agreement and reported the company’s business practices to the NFL.

Prolanthropy, through an attorney, refused to comment on specific questions provided in writing about a half-dozen nonprofits the company has managed, including the Cornerstone Foundation, citing nondisclosure agreements and its clients’ privacy.

Prolanthropy's response:Management company's statement on USA TODAY Network investigation

Tillman’s experience with Prolanthropy came to light as part of a six-month investigation by The USA TODAY Network into charitable organizations founded by prominent NFL players, including 23 of the past 26 winners of the Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year award.

The investigation found the NFL devotes significant energy to lauding its players’ philanthropy and community service but does not vet the nonprofits founded by the men it honors, leaving that responsibility to the players’ teams. And neither the NFL nor the NFL Players Association match their promotional efforts when it comes to educating players on the nonprofit sector.

As a result, players often found nonprofit organizations that stumble for years, award winners and nominees said.

Jackie Tillman said she often fought with Ginn over Prolanthropy charging 22.5% of unsolicited donations — including hundreds of thousands given by the Tillmans themselves — and a cut of the value of in-kind donations the company had no role in obtaining.

“When we got the payment from the NFL for the Walter Payton Man of the Year and they took a percentage, I fought with them about that,” Jackie Tillman said.

“And they were like, ‘Well, essentially we helped him win it.’

“And I was like, ‘But you literally did nothing for that award! It’s not like you had to do work for that!’

“And he was like, ‘Well, we had to send emails.’ So it pisses me off every year when I know the Man of the Year money is going up and then you’re taking a percentage of that money because you think you’ve sent emails and you’ve earned that somehow.”

Tillman also was a finalist for the Payton award in 2011, when the top honor went to Baltimore Ravens offensive lineman Matt Birk, another Prolanthropy client.

Prolanthropy also collected 20% of the “fair market value” of in-kind donations to the Cornerstone Foundation, which included discounted NFL jerseys Charles Tillman acquired for charity auctions and free lane rentals at a bowling alley, the Tillmans said.

“We got to use the facility for free, but they would take a percentage of the $50,000 (in-kind donation) even though there was not $50,000 there,” Jackie Tillman said. “It just started to get muddy, where it was like, ‘Wait a minute. You’re saying we raised this much, but now you’re telling me we don’t have enough funds for this?’ I’m doing work for free on my end, and we’re getting to a point in time where things are not adding up. Numbers are not working.”

Two months after Tillman was named the 2013 Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year, the Chicago Tribune reported that Prolanthropy “skirts best practices” by charging clients a percentage of all donations, an arrangement expert said can encourage abuses, provide reward without merit and imperil the integrity of the nonprofit sector.

Prolanthropy also had solicited donations for players’ organizations before they were granted nonprofit status by the IRS and without registering itself as a professional fundraiser, as required, in nearly two dozen states where it held events or raised money, according to public records cited by the Tribune.

At the time, Prolanthropy was running 21 nonprofits, including two of the last three Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year award winners, and Ginn had proclaimed his company the “largest and most successful” full-service philanthropy management firm in pro sports.

“He tried to really reassure me that it was nothing,” Charles Tillman said, “and I was like, ‘I don’t know, man. This is a national story. This is kind of big. And my name’s on it. This makes me look like I’m stealing money.’”

Prolanthropy's one-stop approach

Prolanthropy sells itself to professional athletes as a one-stop shop for philanthropy creation and management.

It’s an easy and appealing pitch for young, wealthy athletes with little time and nonprofit knowledge.

“When Prolanthropy presented how they run the business, which was, ‘You tell us what you want foundation-wise, and then we run it. We do the inventory, the paperwork, the taxes, the fundraising, events, we’re a one-stop shop,’” Charles Tillman said. “And I was like, ‘This is perfect.’

“I didn’t really know a lot about the foundation business. I just knew that I had a pretty good platform and I wanted to give back. And I’ll take the responsibility for that. That’s my fault for not knowing the charitable work.”

Andy and Jordan Dalton had a similar experience with Prolanthropy.

On the final Sunday of the 2017 regular season, the then-Cincinnati Bengals quarterback threw a last-minute touchdown pass to defeat the Baltimore Ravens and lift the Buffalo Bills into the playoffs for the first time in 17 years.

Bills fans responded by donating $442,000 to the Andy and JJ Dalton Foundation through an unsolicited, viral social media campaign.

Prolanthropy received nearly $100,000 off the top.

Despite the infusion of resources, the Dalton Foundation spent 63 cents of every dollar on charity in 2018. It spent 56 cents of every dollar on charity in 2019.

Dalton, a two-time Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year nominee, had founded the nonprofit before his first game as a pro, after his agent directed him to a marketing representative who put him in touch with Prolanthropy.

The Daltons left the company in 2021, after this reporter's investigation for The Buffalo News, and said the nonprofit will donate all further money directly to hospitals “so 100% of proceeds go to families in need.”

The Daltons and the Dalton Foundation, however, are still featured as clients on Prolanthropy’s website.

Jordan Dalton confirmed to The USA TODAY Network the nonprofit hasn’t been with Prolanthropy for more than a year.

Retired NFL receiver Emmanuel Sanders is likewise still featured as a client on the company’s website despite leaving the company in 2020.

The Emmanuel Sanders Foundation had spent just 41 cents of every dollar on charity over the prior three years.

Prolanthropy, through an attorney, declined to comment about why the company’s website continues to feature professional athletes it no longer represents and nonprofits it no longer manages.

Other athletes listed as clients on the Prolanthropy website include David Johnson, the Cardinals’ 2019 nominee for the Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year, and Von Miller, the Denver Broncos’ 2018 nominee for the honor.

Johnson’s Mission 31 Foundation, which has donated video games, iPads and other electronic equipment to medical facilities in Phoenix and Houston — a common program run by Prolanthropy-managed nonprofits — and little more, spent just 27.2 cents of every dollar on charity since its inception 2017 through 2020, according to federal tax records.

Miller’s nonprofit, Von’s Vision, which provides low-income students with eye care and glasses, has spent 59 cents of every dollar on charity, according to its three most recent federal tax returns.

Numbers don't add up

Delanie Walker said he hired his publicist when he joined the Tennessee Titans in 2013 because he wanted to win Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year.

“I strived to get the Man of the Year award, the big one, at the end of the year for the Super Bowl,” Walker told The USA TODAY Network. “That’s why I hired (my publicist). And I’m sure other guys, that’s why they hired publicists and that’s why they hired the bigger companies to run their foundation.

“My goal was to be Man of the Year for the Tennessee Titans and also be one of the top players on the team. And that’s the only way I knew I could do it, was hiring somebody to help me.”

Prolanthropy had run a nonprofit for Titans quarterback Jake Locker, and when he retired, the company contacted Walker’s new publicist to inquire about his interest in their services.

He was impressed by their roster of clients.

“I’m like, ‘OK. If they have them players, then they’ve got resources where they can reach out to guys with bigger pockets,’” Walker said. “And obviously, that’s what we’re doing it for, to raise money for our cause.”

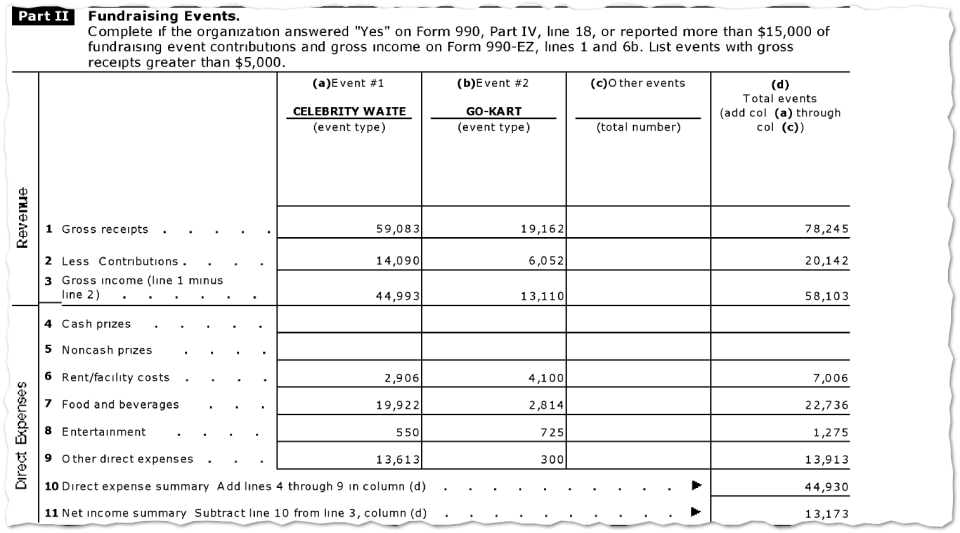

In 2015, the Delanie Walker Gives Back Foundation reported two fundraising events on its tax returns and to the media.

Celebrity Go-Karting Challenge: The nonprofit announced the event raised $40,000, but tax records show it raised $11,000 after expenses.

Titans & T-Bones: The nonprofit announced the dinner raised $80,000, but tax records show it raised $22,000.

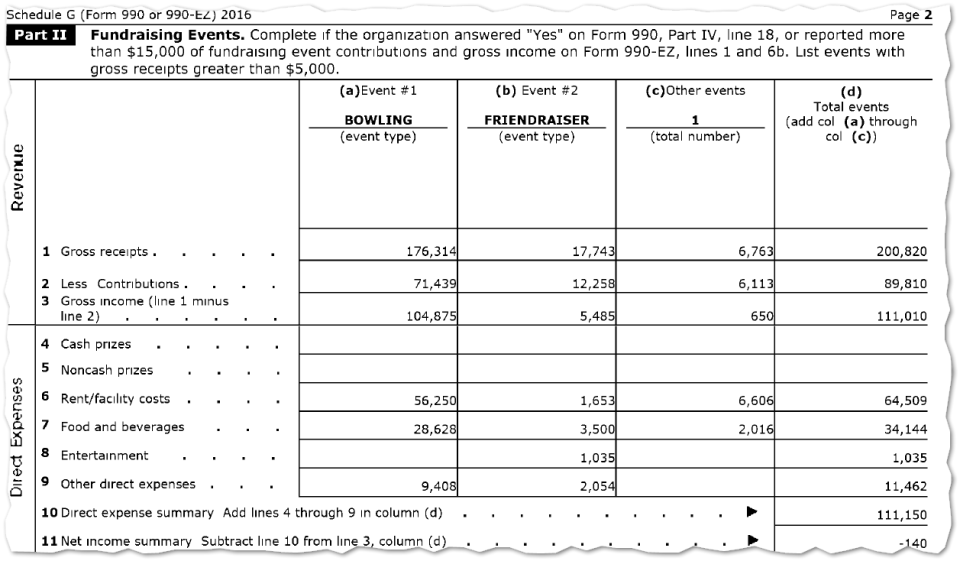

In 2016, the nonprofit hosted the Titans Ten Pin bowling fundraiser in Franklin, Tennessee. Tax records show the event generated $176,000 in revenue, incurred $95,000 in expenses and raised $82,000. The nonprofit announced the event raised $80,000.

But when Walker and his publicist inquired about the money because he wanted to build school libraries, they said they were told the nonprofit only had $10,000 in its account.

“I was deceived,” Walker said. “I was struck. Because it was like, ‘You put this out there that we raised $80,000 for my charity, and then at the end of the day, behind closed doors it’s only $10,000? Really?'”

Tax records show direct expenses for the bowling fundraiser included $56,000 in rent and facility costs.

Walker said his nonprofit rented half of a bowling alley around the corner from where he lived, and that he knew management because he and running back Derrick Henry bowled there all the time. Walker said he does not believe it cost $56,000 to rent the lanes.

Tax records show direct expenses also included $29,000 in food and beverage costs.

Walker said those in attendance were served pizza and wings — “bowling alley food” — and questioned the amount of this expense, as well.

He also questioned an additional $9,000 in “other” expenses.

Prolanthropy did not provide The USA TODAY Network with documentation substantiating these expenses, as requested, or explain what happened to the $82,000 the event raised after these expenses.

Weeks after Walker and his publicist said they began asking questions, Prolanthropy declined to renew its management contract for the player’s nonprofit and Ginn emailed Walker about his desire to have a “very open and honest discussion” about his vision for the future of his nonprofit.

No conversation occurred.

“They took advantage of everybody in the circumstance,” Walker said. “And used my name to do it. Now that I sit back and I hear about the tax returns and the money that they generated and the money that they said they spent for these events, it’s mind-blowing, and I just don’t want anybody else to experience something like that. If we can stop it now, this is the opportunity to do so.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: NFL players raise questions about Prolanthropy nonprofit

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies