The Death and Rebirth of the Porsche 911

The mid-Seventies was a difficult time for Porsche. The German brand found itself caught off-guard by—or intentionally disregarding—a series of global changes, including a dramatic rise in oil prices, a stagnating economy, and increased consumer and government concern over fuel economy, tailpipe emissions, engine and exhaust noise, and occupant safety.

The Porsche 911 of the time had clamorous, air-cooled, rear-mounted engine. Its compact size and intentionally difficult handling characteristics—the back end would swing out if a driver let off the accelerator in turns, surprising many—made it particularly unfit for meeting these new requirements. The model, already a decade old, was cut off from new investment by the automaker, and by the middle of the decade, sales began to erode. This only reinforced its vulnerability.

Add to that, the Porsche family had withdrawn from the management structure of the company in 1972, and technical operations were consolidated under Ernst Fuhrmann, who had been the lead engineer on the brand’s signature performance and racing vehicles, including the 911 Turbo, 934, and 935.

Under Fuhrmann’s aegis, Porsche began development of a new family of vehicles that would attempt to address the 911’s shortcomings and offer a viable replacement. These cars would undo decades of Porsche tradition by placing a water-cooled engine up front. They would also feature cutting-edge, crash-resistant design, something unavailable in the 911, an anachronism that could trace its roots back to the Nazi’s rattletrap Volkswagen, which company founder Ferdinand Porsche had designed for Adolf Hitler.

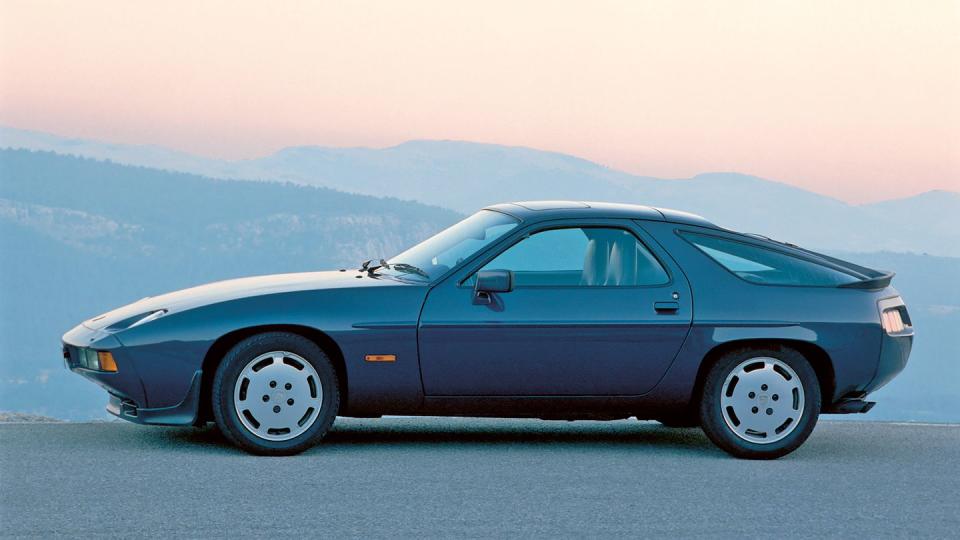

The resulting car, the 928, was based on a transaxle system, which placed the transmission at the rear of the car. This provided a nearly perfect 51/49 front-rear weight distribution, creating a more stable and predictable driving experience. Aluminum body panels kept down weight, promoting efficiency. The front-mounted V-8 was more readily adaptable to new emissions and noise regulations. And the packaging allowed for creature comforts craved by luxury vehicle buyers.

The 928 launched in 1978, and was extremely well reviewed for its styling, stability, amenities, and performance. It was relatively easy to drive quickly—it rounded the Nürburgring just as fast as a 911, with less difficulty. But it didn’t sell like a 911. Another front-engine car, the 924, had been developed by VW, but was sold as an entry-level Porsche starting in 1977. It was criticized for being cheap and underpowered.

1980 was Porsche’s worst year ever. The brand showed its first loss; unsold cars, mainly 924s, began piling up behind the factory. Morale was at a nadir. But the front-engine cars were still thought of as the right choice to enhance performance and sales within the confines of the aforementioned global constraints. The 911 was aged and outmoded, with no future. The decision was made to discontinue the model after 1982.

The Porsche faithful were apoplectic. The company decided to replace Fuhrmann. His successor was Peter Schutz, a German Jew whose family had fled the Nazis for America. Schutz had worked as an engineer at Caterpillar and an executive at Cummins. He went on a listening tour with Porsche stakeholders and determined that the 911 was the lifeblood of the company—key not just to its fiscal success, but to its identity as a sports car maker. The quirky machine provided a sense of driving pride and accomplishment to its customers.

Schutz decided that in order to revamp the brand, Porsche had to play to its strengths as an innovative and iconoclastic company. He asked Ferry Porsche, son of the founder of the company, what he thought should be done. Porsche suggested Schutz should build his dream car. The newly-installed executive thus decided not to make Porsche more accessible, but to move it further upscale, while emphasizing its core equities.

The result of this breakneck skunkworks project was the 911 Cabriolet, a beautifully rendered convertible version of the venerable icon. It was built in eight weeks by the same employee who created the 356 Roadster, the last full convertible Porsche had offered. Though the Cabriolet cost 20 percent more than the coupe, it sold handily, and reinvigorated consumer interest in the long-in-the-tooth model. This was enough to encourage Porsche executives, at Schutz’s recommendation, to give the 911 a stay of execution.

Porsche turned a large profit in 1982, and invested huge amounts in developing a new 911, launched in the 1984 model year. Though the brand’s range has expanded significantly in the intervening four decades, the 911 remains the pinnacle of Porsche's identity.

During a contemporary interview, Dr. Porsche was asked what his favorite Porsche car was. Schutz answered for him: “We haven’t built it yet.”

I am indebted to the following books for the research on which this story is based.

Cars Are My Life: Professor Dr. Ing. H.c. Ferry Porsche, with Gunther Molter. Patrick Stephens Ltd., 1989

The Driving Force: Extraordinary Results with Ordinary People: Peter W. Schutz. Leadership Publishing, 2005

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies