The dark story behind Marilyn Monroe and ‘Mr Z’

In Andrew Dominik’s controversial new film, Blonde, which has just dropped on Netflix, Ana de Armas’s Marilyn is beset by the unwelcome and aggressive attentions of powerful men, from Bobby Cannavale’s Joe DiMaggio to Caspar Phillipson’s JFK.

Yet Blonde presents one character as its truly dark-hearted antagonist, in the form of a producer and studio executive named only as “Mr Z”. As portrayed in the film by David Warshofsky, he is shown raping Monroe in a hard-to-watch scene that was in part responsible for its being given a rare NC-17 rating, something that few mainstream films are awarded today.

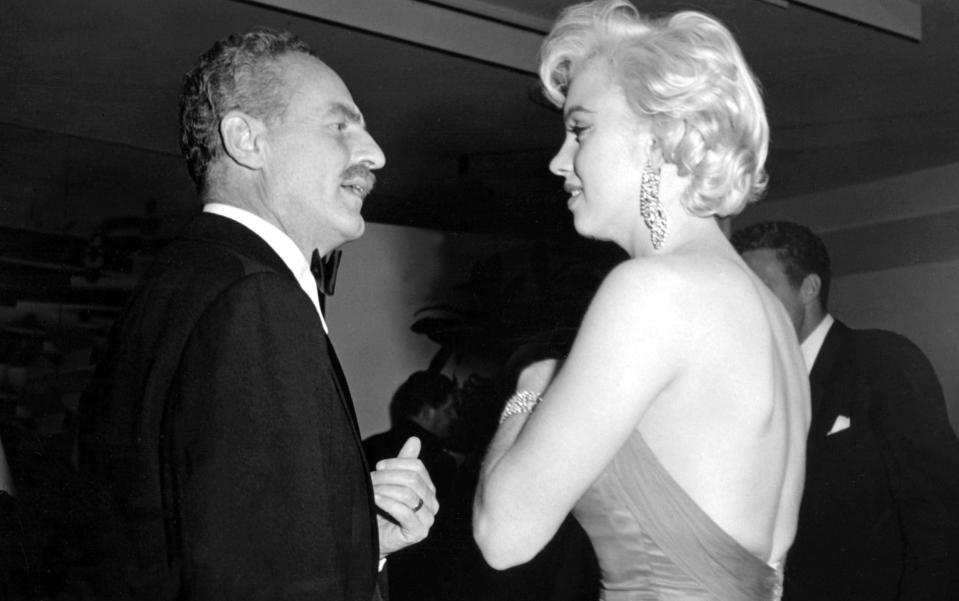

The character is anonymous, but it is assumed that Mr Z is based on Darryl F. Zanuck, one of the most influential producers of the 20th century – and, not coincidentally, the man who began Monroe’s career. Unquestionably, Mr Z emerges from Blonde as a despicable and reprehensible figure, using his power to assault innocent women with impunity. There's no evidence that Zanuck himself actually raped Marilyn, yet the truth behind his reign of terror is dark and disquieting as it is.

When the producer died in 1979, at the age of 77, he was lauded as one of the true kings of Hollywood. During the course of a career that had begun in the silent era and had stretched into the Seventies, he produced cinematic classics that included the first “talkie”, The Jazz Singer, the black comedy All About Eve and the war epic The Longest Day.

During his time as a studio executive at 20th Century-Fox, Zanuck acquired a reputation for producing films that dealt with contemporary social issues that other studios preferred to avoid. These included Gentlemen’s Agreement in 1947, starring Gregory Peck as a reporter who finds himself beset by anti-Semitism when he poses as Jewish, and the 1949 psychological drama The Snake Pit, with Olivia de Havilland as a woman incarcerated in a mental hospital against her will. After the film’s release, the widespread horror at the depiction of society’s inhumanity towards the mentally ill led 13 states to change their laws around mental health issues.

Zanuck might have considered himself a good, even great figure in the often-fickle world of entertainment, producing entertaining but also important pictures that shone an often unflattering light on aspects of American life that were not being tackled elsewhere.

But one feature of Zanuck’s own life that was never explored, even glancingly, in any of the films that he produced was what might euphemistically have once been called the “casting couch”, and which can be more accurately described as the systematic rape and abuse of young women who wished to build careers as actresses in the so-called “Golden Age” of Hollywood.

There was precisely nothing golden about the treatment that he meted out. Zanuck liked to spend his days “in conference” with a succession of aspiring actresses between 4pm and 4.30pm, and thus became notorious for his actions during this time. One visitor was taken aback to find that, when she visited Zanuck’s office, he was already naked from the waist down and prepared for the afternoon’s activities.

Zanuck saw himself less as an abuser and more as a womaniser. He once made an advance to Joan Collins, when she was attempting a short-lived Hollywood career, with the immortal words: "You’ve had nothing until you’ve had me.” Although he was married to the long-suffering actress Virginia Fox from 1924 until his death – they separated in 1956 due to his continual adulteries, but they remained in contact and she looked after him in his final decline in the Seventies – he was notorious for attempting to launch the acting careers of good-looking but wooden actresses, who he referred to as “my girlfriends”.

One of these was a French chef called Geneviève Gilles, who met Zanuck when she was 19 and he was 63. Despite the conspicuous age difference, she professed to find him irresistible, saying after his death: “His age didn't bother me. He was wonderful, very powerful and smart. About sex, he was like Picasso, I think”.

One can only imagine that Gilles had been thinking of Picasso’s Guernica when it came to her lover’s sexual prowess – a howl of primal anger produced by a terrible event. She was the last of Zanuck’s protégées, who he cast in the 1970 comedy Hello-Goodbye, opposite Michael Crawford. Her lack of acting ability did not deter Zanuck from taking personal charge of the film’s production but by this stage whatever talent the producer had had long since deserted him. The film attracted terrible reviews and was a notable box office flop.

Gilles duly returned to obscurity, only surfacing again after Zanuck’s death to claim that she was owed $15 million in his will and that she had been his constant companion between 1965 and 1973. She was unsuccessful, but the cynical might have muttered that she had certainly earned her money in the eight years that she had undergone his attentions.

Gilles, along with the likes of Bella Darvi, Juliette Gréco and Irina Demick, had at least been relatively fortunate. In exchange for satisfying Zanuck’s desires, they were all given the opportunity to appear in films that he produced. The producer even went so far as to leave his wife for Darvi, only to return, shamefaced, when the actress revealed her bisexuality to him; despite the apparently liberal sentiments that Zanuck espoused in the films that he produced, being involved with a bisexual woman was a step too far.

Gréco, meanwhile, managed to move on from Zanuck and enjoyed a successful singing career in her native France. The producer was only one of a starry cast of lovers who included Miles Davis, Quincy Jones and Albert Camus, and her relative indifference to the mogul frustrated him so much that, during the production of her 1960 film Crack in the Mirror, he all but took control of the picture, overruling its director Richard Fleischer and behaving, in Flesicher’s words, “like a spoiled child”.

Yet Zanuck’s love affairs, if they could be called that, were at least consensual. It was his relationship with Marilyn Monroe that suggested an altogether darker and more unpleasant side to him. When the young Norma Jeane arrived in Hollywood in 1946, at the age of 20, she already had a reputation for being a pin-up girl who had appeared on magazine covers, and who wanted to get into the movies.

It was inevitable that she, like so many others before and since, would be ushered through the subterranean tunnel on the Fox Studios lot into Zanuck’s green-panelled office for his 4pm “conference”. Zanuck’s biographer Marlys Harris wrote of these appointments that “He was not serious about any of the women. To him they were merely pleasurable breaks in the day – like polo, lunch and practical jokes.”

It was always made clear to the young women what the expected deal was. Sleep with Zanuck – once, or repeatedly – and they could expect a contract. Refuse to do so, and they were not only liable to blacklisted by Fox, but would find it impossible to be received anywhere else, and would be forced to return to whichever small town they had so eagerly headed off from, complete with dreams of a Hollywood career.

Yet whatever happened between Monroe and Zanuck proved to be unsatisfactory for both parties. She was given a screen test by the Fox executive Ben Lyons, but Zanuck was unenthusiastic about the results; he grudgingly gave her a six-month contract with Fox, ostensibly to keep her away from the clutches of the rival RKO studios, but more likely so that he could retain her loyalty, and sexual favours.

How the young Monroe felt about being so objectified by this older and powerful man can only be surmised, but it was surely Zanuck – along with many others of his kind – that she was thinking about when she wrote in her unfinished memoir My Story that “Phoniness and failure were all over them. Some were vicious and crooked. But they were as near to the movies as you could get. So you sat with them, listening to their lies and schemes. And you saw Hollywood with their eyes – an overcrowded brothel, a merry-go-round with beds for horses.”

Perhaps Monroe, at the age of 20, was already too old for Zanuck. In addition to his inclinations towards legal starlets, he was also fixated on younger women, such as Linda Darnell, the so-called “girl with the perfect face”. She began her career at the age of 15, although the studio’s publicity department claimed that she was 19, and the gossip columnist Louella Parsons took delight in writing about Darnell’s conspicuous loyalty to Zanuck, the man who discovered her.

Although Darnell breathlessly said of her experience that, “At first, everything was like a fairy tale coming true. I stepped into a fabulous land where, overnight, I was a movie star”, it seems inevitable that she, too, took her place upon Zanuck’s couch one afternoon, and hoped for the best.

Since the exposure and downfall of Harvey Weinstein – the closest thing to a latter-day Zanuck that Hollywood has had – there is vastly greater awareness of the malign and toxic influence that powerful and influential men in the film industry can have over younger women.

Yet Zanuck was not alone. The likes of Harry Cohn – believed to be the influence for the similarly venal film producer Jack Woltz in The Godfather who wakes up abed with a horse’s head – and Louis B Mayer similarly used their unlikely charms and promises of a lucrative career to force themselves on the actresses who were then (sometimes) cast in their pictures. But, as Blonde so terrifyingly and poignantly reminds us, an entire industry and countless classic films were based on this legacy of abuse.

Blonde is on Netflix from today

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies