Dancer, singer … spy: France’s Panthéon to honour Josephine Baker

In November 1940, two passengers boarded a train in Toulouse headed for Madrid, then onward to Lisbon. One was a striking Black woman in expensive furs; the other purportedly her secretary, a blonde Frenchman with moustache and thick glasses.

Josephine Baker, toast of Paris, the world’s first Black female superstar, one of its most photographed women and Europe’s highest-paid entertainer, was travelling, openly and in her habitual style, as herself – but she was playing a brand new role.

Her supposed assistant was Jacques Abtey, a French intelligence officer developing an underground counter-intelligence network to gather strategic information and funnel it to Charles de Gaulle’s London HQ, where the pair hoped to travel after Portugal.

Ostensibly, they were on their way to scout venues for Baker’s planned tour of the Iberian peninsula. In reality, they carried secret details of German troops in western France, including photos of landing craft the Nazis were lining up to invade Britain.

The information was mostly written on the singer’s musical scores in invisible ink, to be revealed with lemon juice. The photographs she had hidden in her underwear. The whole package was handed to British agents at the Lisbon embassy – who informed Abtey and Baker they would be far more valuable assets in France than in London.

So back to occupied France Baker duly went. “She was immensely brave, and utterly committed,” Hanna Diamond, a Cardiff university professor, said of Baker, who on Tuesday will become the first Black woman to enter the Panthéon in Paris, the mausoleum for France’s “great men”.

“There’s a lot we don’t know, and may never know, about exactly what espionage work she did, the secrets she actually transmitted,” said Diamond, an expert on second world war France who is researching a book about Baker’s wartime exploits.

“Bits of her life we know a great deal about: the humble beginnings in Missouri, the international sensation of 20s and 30s Paris, the US civil rights activist, the mother of an adopted, multiracial family … That’s not the case for the resistance heroine.”

President Emmanuel Macron decided this summer that 46 years after her death, Baker would become only the sixth woman to be memorialised in the Panthéon in a ceremony on 30 November – the anniversary of the marriage to Jean Lion that allowed her to acquire French nationality.

Born Freda Josephine McDonald in St Louis in 1906, Baker left school at 12 and landed a place in one of the first all-Black musicals on Broadway in 1921. Like many Black American artists at the time, she moved to France to escape discrimination.

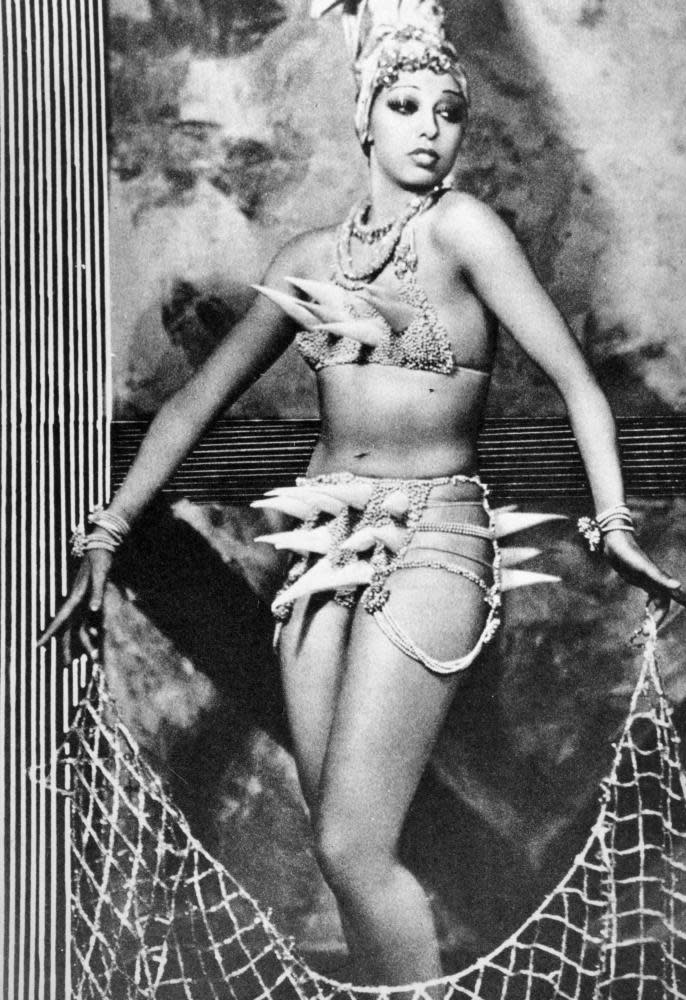

Photograph: MARKA/Alamy

Emerging from the chorus line of La Revue Nègre, she became a huge star, tapping into colonialist, racist and male sexist fantasies in performances that both shocked and delighted audiences and won admirers from Ernest Hemingway to Pablo Picasso.

Dubbed “the Black Venus”, she danced the charleston in nothing but a string of pearls and a skirt made of 16 rubber bananas, performed with a snake wrapped suggestively round her neck, strolled down the Champs-Élysées with her pet cheetah, and became an international superstar.

Off stage, as the hit songs and starring movie roles succeeded one another, Baker cultivated a scandalous private life, having affairs with men and women including the novelist Colette, the architect Le Corbusier and the crown prince of Sweden.

After the war she fought for equal rights as energetically in public as at home, speaking before Martin Luther King at the 1963 March on Washington and adopting 12 children from around the world to live with her in her chateau in the Dordogne.

Her wartime spying activities, however, are – for obvious reasons – rather less reliably documented. Much of what is known, said Diamond, who recently published an initial, primary source extended essay on Baker’s war, comes from a book Abtey published in 1948.

“He was a maverick figure – a bit of an operator,” she said. “He was clearly telling his own story, making his own case, at least as much as he was telling hers. He was not, let’s say, disinterested, and it’s proving hard to track down original source material to verify his account.”

Related: The enigmatic Josephine Baker - interview: archive, 26 August 1974

What is sure, though, is that Abtey recruited Baker after meeting her – reluctantly – in late 1939, introduced by a patriotic promoter. Determined to show her gratitude to the country that had made her and contribute to the war effort, the star was already performing for Allied troops, and working with refugees for the Red Cross. (Later in the war, she would refuse to perform for Germans).

“She had an unconditional love for France. She wanted to do her bit for the patrie,” said Diamond. “She also intuitively understood the dangers of Nazism. She helped Lion and his Jewish family escape the Germans. She had little formal education, but she associated Nazism with the racism she’d known.”

Abtey was wary of what Baker could offer and sceptical of what a female superstar could realistically do. But she talked him into setting her a test, sending her to the Italian embassy where she extracted sensitive information from an attaché and successfully brought it back.

Abtey, who is widely assumed to have been the singer’s off-and-on lover, became her handler. He trained her in basic spycraft techniques – invisible ink, writing up your arm, reading upside down – but soon saw her real usefulness lay in her magnetic charm, and effortless ability to switch roles. She was a performer, and spying would be her greatest part.

“She subverts our notion of what spying is,” said Diamond. “It’s subterfuge, going under the radar. But here’s this huge star, hiding in plain sight. No one suspects her. And most importantly, she can travel anywhere, and take an entourage with her. For Abtey, that’s priceless. As much as she’s a spy, she’s an espionage facilitator.”

From early 1941 onwards, that is what Baker did. Instructed by London to base themselves in North Africa, she and Abtey went to Morocco. The singer travelled from Casablanca to Lisbon, Seville, Madrid, Barcelona, giving concerts, attending receptions in her honour, flattering attachés, politicians and envoys – and passing handwritten notes, generally pinned to her bra, to British agents.

For some months, she was seriously ill with blood poisoning, possibly after a miscarriage. But even while she was convalescing, her hospital room became a venue for secret meetings, with diplomats, personalities and officials summoned to Baker’s bedside where gossip was exchanged and secrets smuggled out.

With North Africa, following the Allied invasion of 1942, now De Gaulle’s operational and administrative springboard, Baker resumed travelling across the region after her recovery, giving concerts for the troops, fundraising for the resistance - and gathering intelligence as she went. In 1944, she enlisted as a women’s air force auxiliary.

“She absolutely saw herself as a soldier,” Diamond said. “She saw what she did as the best way, the most effective way, for her to fight her war. And while there’s this cloud of uncertainty over what exactly she passed on, she certainly passed on plenty.”

Ultimately, said Diamond, Baker “realised very early that she could use her celebrity for a cause. And she did. She took huge risks. She deserved her Légion d’honneur – and her Croix de Guerre.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies