Crash-packed day marks moment the world slipped past GB on the track

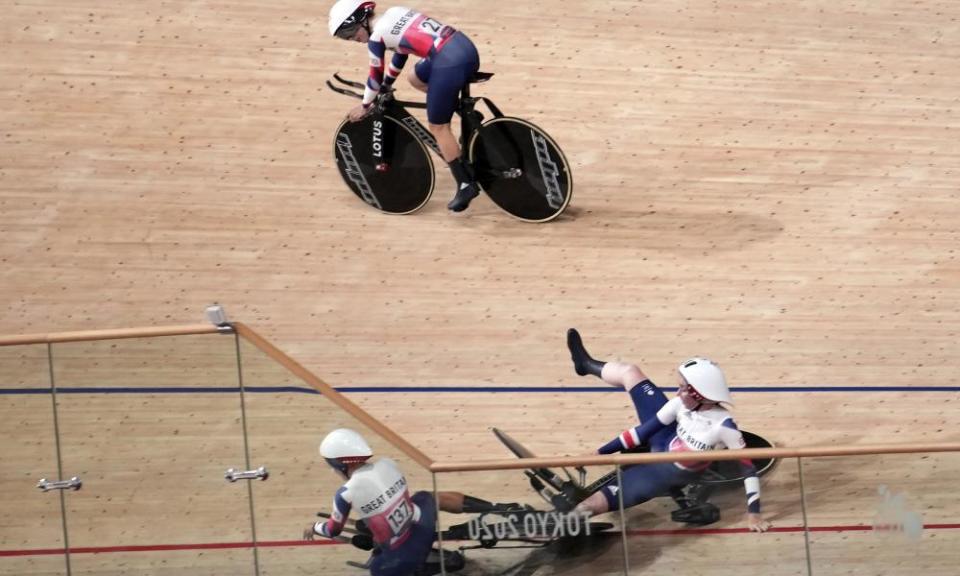

On a day that looks to have marked the end of Great Britain’s dominance of track cycling at Olympic level, there were symbols aplenty that the world has moved on, beyond the bald facts of the medal table. Dramatic crashes involving the men’s and women’s team pursuit squads closed the run of Olympic Games when one British gold medal followed another in seamless style, the hallmark of the track action in Beijing, London and Rio.

In all the chaos, the sprinter Jason Kenny became Britain’s most decorated Olympian with his eighth medal in total, a silver in the team sprint, putting him level with Bradley Wiggins; Kenny remains level with Chris Hoy on six golds. While his wife, Laura, pushed her medal tally upwards with a silver in the team pursuit, Tokyo marked the end of her remarkable unbeaten Olympic run. It will be scant consolation for an athlete of her competitive spirit but it required an astonishing world record from Germany to deny her a fifth gold in five attempts.

Related: GB dethroned in men’s Olympic team pursuit amid Danish crash controversy

In a distant past, the timed disciplines on the track were relatively predictable, albeit spectacular, but Jason Kenny’s desperate fight to maintain contact with the second rider in the team sprint trio, Jack Carlin, illustrated just how close the riders have to go to their breaking point. It is barely surprising they go beyond it, which was underlined when the team pursuits produced as many crashes as might be expected in the bunch disciplines later in the week.

There was equipment failure as in the case of the Australian Alex Porter’s handlebar on day one, but apart from that the search for ever greater speeds has pushed the riders up to their limits and sometimes beyond, as was seen when the Danish lead rider, Frederik Madsen, shunted into Charlie Tanfield on the final lap of their second-round match, simply because Madsen was so intent on keeping to the black line at the foot of the track.

Similarly, when Katie Archibald ran into the rear wheel of Neah Evans after crossing the line in their team pursuit match against USA, that could be put down to exhaustion from driving the team to a world record to put them in the final. The record progression in the women’s 4,000m team pursuit is as remarkable as that in the men’s, perhaps more so given that the discipline only moved to four women and 4,000m after the London Games.

“I’ll just keep turning up and see what happens,” said Laura Kenny and while she is back on Friday for the Madison, along with Archibald, Jason returns for the start of Wednesday’s session with qualifying for the match sprint. On the other hand, there is no way back for the team pursuit stalwart Ed Clancy, whose 16 years racing with the Lottery-funded squad ended on Tuesday when he was ruled out of the second round due to a resurgence of the back injury that has plagued him since a bizarre accident with a suitcase in 2014.

Part of the first generation to go through the British Cycling academy founded by Rod Ellingworth in 2003-04, the 36-year-old closed his career with the fastest ride by a British quartet in qualifying on Monday. Although the team-pursuit game has moved on dramatically in the past few years, and Clancy and company are no longer the squad’s medal bankers, he can look back at three Olympic gold medals, five world titles at team pursuit and one in the omnium in 2010, and a string of world records over eight years and three Olympic cycles.

“I’d have rather gone round there tomorrow in 3min 38, high-fiving the crowd with my fourth gold medal in hand on the podium, but I’m glad I’ve got this far,” he said. “I’m glad I’ve gone down kicking and screaming and fighting.

Related: Laura and Jason Kenny win silver medals in Olympic team cycling finals

“Managing the injury has been the issue for the last seven years; everything was going well [but] I was 5% off it yesterday and that’s enough to cost you in the last kilo.”

Clancy made his international debut at the 2005 world championships in Los Angeles, where he was part of a gold medal-winning pursuit team alongside the generation that had emerged at the Sydney Games. Through the Beijing Olympic cycle he developed into the prototype of the “mixed” athlete, part sprint, part endurance, who made the team pursuit faster and faster in recent years.

As well as watching Tour de France winners check in and out of the squad, Clancy has witnessed an astonishing increase in speeds. At the start of his career, teams rarely broke the four-minute barrier, whereas now the target is 3min 40sec. He is the most self-deprecating of athletes, but to get as far as he has, gammy back and all, reflects massive fighting spirit. In the intensity of 21st century competition, few cycling careers at Olympic level will last as long.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies