COVID-19 means more preschool-age kids won't be ready for kindergarten

Cheryse Singleton-Nobles knows her 2-year-old son is regressing.

While the toddler is getting the hang of colors, numbers and shapes, she says, “he’s back to the stage of ‘me, me, me.’” He doesn’t want to share anymore. He struggles to follow a routine and gets distracted by all his toys.

Singleton-Nobles, 47, attributes this backtracking to the COVID-19 pandemic, which recently forced her son’s free Chicago preschool to close its campus.

That preschool, an early-learning center that belongs to a national network of Head Start-funded programs called Educare, shut its doors in the spring but managed to reopen at limited capacity in the fall. The center had to revert to distance learning again in mid-November amid a surge in COVID-19 infection rates.

Now, her son – like countless other young children across the country – is sliding in his social-emotional skills. And those losses could be devastating for these children's long-term success. Preschool years are among the most formative of a child’s life. A student who starts kindergarten without preschool is more likely to repeat a grade, require special-education services or drop out.

“Unfortunately, for children, the impact of this pandemic will be felt for years,” said Dimitri Christakis, a pediatrician who directs the Seattle Children’s Hospital Center for Child Health, Behavior and Development.

Many kids were already behind

For America’s low-income children, high-quality opportunities to prepare for kindergarten were already in short supply before the pandemic hit. Nationally, child care was out of reach for many Americans, costing as much as $9,600 on average last year, an analysis by Child Care Aware of America found.

Head Start, a federal early-childhood education program designated for low-income families, served just 36% of eligible 3- to 5-year-olds. Early Head Start reaches even fewer families, enrolling only 11% of eligible infants and toddlers.

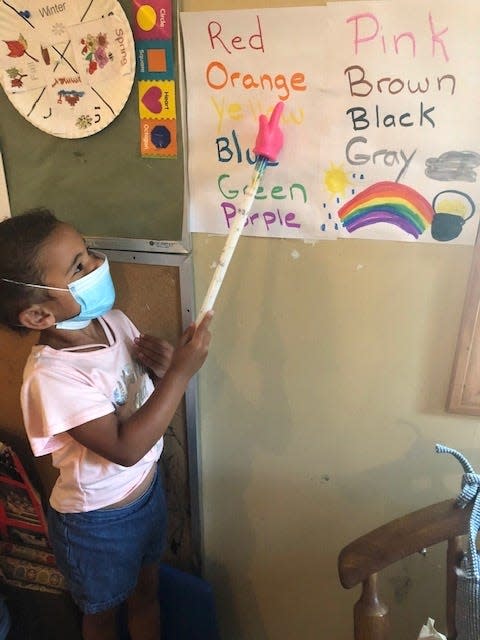

As a result, as many as half of low-income children already were starting kindergarten without being ready for it. A child is considered “kindergarten ready” if, for example, she speaks in complete sentences most of the time, can identify at least five colors and knows her first and last name.

Most brain development occurs before age 5 – the brain triples in size in the first two years of life – which is why a child's learning experiences during that window are so predictive of her success later on. “Children are born wired to learn,” Christakis said. “Early-learning experiences lay the foundations of their minds for the rest of their lives.”

A slew of studies show that children who attend quality early-learning programs are more likely to enter kindergarten with a solid grasp of language and math and to have positive relationships with their parents, for example. They’re also less likely to struggle with behavioral problems. Some research suggests students who enter kindergarten without having learned how to share, express their emotions and listen to instructions, for example, are less likely to graduate high school.

Early-childhood education, advocates stress, isn’t just babysitting. That’s particularly true when such education takes place in a formal setting. (Child care centers, while often more expensive, often strive to meet child development standards and therefore are better for kids' development than home-based child care, research shows.)

How badly are kids slipping? 'It's sizable'

It’s hard to quantify how much the pandemic is undermining children’s readiness for kindergarten. Schools such as those in the Educare network are in the process of rolling out virtual assessments designed to measure students’ achievement levels, but experts warn that the findings from those evaluations will need to be taken with a grain of salt. Assessments performed by parents – versus a trained professional – are subject to all kinds of complications.

But anecdotal evidence – paired with existing research on early-childhood education – suggests the damage could be severe.

“We won’t know the full impact for a while,” Christakis said, “but there’s every reason to believe that it’s sizable.”

And it's likely worse for low-income children.

Their families have faced the double whammy of soaring preschool costs and widespread job insecurity – not to mention fears of contracting COVID-19, which has disproportionately infected people of color.

Is day care safe during pandemic? It depends. Here are some guidelines.

Since the pandemic hit, the cost of high-quality early childhood education has only increased. Research by the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank, shows the monthly cost of center-based child care has grown by 47% on average nationwide. The trend has been particularly pronounced at programs for 3- and 4-year-olds, largely due to the significant decrease in recommended class sizes to reduce potential coronavirus spread.

In many cases, child care is simply no longer available. A survey conducted this summer by the National Association for the Education of Young Children found 18% of child care centers nationwide had closed indefinitely amid the surge in operational costs.

Even if parents can find an opening for their child or afford the fee, many are choosing not to send their children to preschool, out of fear of exposing them to the virus. And while some programs, including many of Educare’s 25 schools, have virtual programming, uneven internet access means many families don’t have that luxury.

Lots of juggling, parents' stress high

The upshot: Even fewer young children than before the pandemic are getting the preparation they need to succeed in school. While enrollment is down for all schoolchildren, the dip is especially stark in kindergarten and preschool, according to an NPR analysis of data from 60 of the country’s school districts. The average drop in kindergarten enrollment, for example, was 16%.

Initial data out of some states paint an even grimmer picture for preschool and child care. In Colorado, for instance, enrollment for infants, toddlers and preschoolers as of July had returned to only roughly half of what it was before the pandemic.

Singleton-Nobles’ son is relatively lucky in that he’s still getting some formal education, if only virtually. Singleton-Nobles is also better equipped than many parents to guide him in his learning: She runs a licensed day care in her home. (She sends her son to a Head Start program in part so he can socialize with and learn from peers in a formal setting.)

Still, the virtual programming, which consists of two 15-minute group sessions per day, hardly compares to the education he typically receives. And Singleton-Nobles finds herself overwhelmed as she tries to juggle her paid job with that of being her son’s primary educator.

Parents who’ve taken on the role of early educator – if they even have the time and resources to do so – are under unprecedented levels of stress, potentially inhibiting their abilities to provide structured learning. As with Singleton-Nobles’ son, virtual programming has to be whittled into short chunks in part to accommodate children’s attention spans.

Indeed, it can also be especially difficult to engage young children in distance learning. They learn best when their learning is experiential – when they can touch and handle objects and gauge the reactions of their educators.

It’s also hard to give young children what Jenny Stillwaggon Radesky, a pediatrics professor at the University of Michigan Medical School, described as “microbits of feedback” in a virtual setting. As an example, Stillwaggon Radesky pointed to a situation in which an infant smiles or laughs or coos. An adult may respond to the act by smiling or laughing or cooing, too, an intuitive form of positive reinforcement that shows the baby how her behavior affects those around her.

Quality early-learning programs recognize the larger power of those microbits of feedback, and they’re deliberate about how that feedback is delivered.

“You need an individual who is actively engaged in that process, monitoring and supporting their learning throughout day,” said Angie Lampkin, who directs Educare Chicago. “Not all parents understand (a young child’s) developmental progression, and that’s where the teacher comes into place.”

Absent center-based schooling, young children also are missing out on early-intervention services they may have received otherwise – specialists who help them develop their fine and gross motor skills, for example.

“You just don’t get that same level of observation and support that you would in an in-person classroom,” said Cynthia Jackson, who leads the Educare Learning Network.

The impact is particularly pronounced on low-income children who tend to rely on school-based services, said Stillwaggon Radesky, whose clinical work focuses on developmental and behavioral problems among low-income children. Now that she’s tested many of her patients via video versus in-person, she said, it’s a lot harder to see how they play and work through other activities.

Beyond the limitations of virtual early learning, many children are also missing out on physical activity, which promotes healthy development and, often, playtime with their peers. Meanwhile, centers that remain open often have to limit students’ interaction, relegating them to their own play areas and thus limiting their ability to practice sharing.

It’s in those moments, after all, that children build social intelligence – how to manage disputes and negotiate with a friend and be likable. Research shows such intelligence is a great predictor of one’s success in school and in life.

From air hugs to airplane arms: What reopening day care centers look like during COVID-19

Then there’s the stress of the pandemic in and of itself, which could lead to or compound the kinds of early-childhood traumas that can undermine later success in school. Children are like sponges and feed off their caregivers’ stress, which can make it all but impossible to learn and interfere with the brain’s biology, affecting how it develops.

'Keep a child's mind engaged'

The bright side is that children are remarkably resilient. And parents, as Stillwaggon Radesky explained, are more empowered to offset the losses than they may realize. While they may not have the training needed to foster their children’s academic progress, they can invest their energy in teaching them other skills – whether it’s how to use the potty or how to regulate their emotions.

“There are learning opportunities throughout the day that can keep a child’s mind engaged,” Stillwaggon Radesky said.

But schools can't just bank on kids' resilience. Experts and advocates say an infusion of federal money is needed to ensure the country’s youngest children thrive after the dust of the pandemic settles. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, which Congress passed in March, allocated just $3.5 billion in block grants to improve access to child care. A separate $50 billion proposal – introduced in the summer to offset that shortfall – has yet to get approval from the Senate.

And some researchers argue more money for better early learning isn’t enough, either. For the benefits of such opportunities to stick, recent studies suggest, children will also need to receive quality elementary education. And that, too, is hanging in the balance during the pandemic.

“The United States has extracted an enormous sacrifice from its youngest citizens to protect the health of its oldest,” notes a recent study co-authored by Christakis analyzing the potential years of life lost due to pandemic-era primary school closures. Even though relatively few children are experiencing the medical consequences of COVID-19, Christakis said, “they are bearing the burden of … all its ancillary effects.”

Correction: A previous version of this story gave the incorrect title for Angie Lampkin. She directs Educare Chicago.

Early childhood education coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from Save the Children. Save the Children does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: COVID at daycare: Online preschool means fewer ready for kindergarten

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies