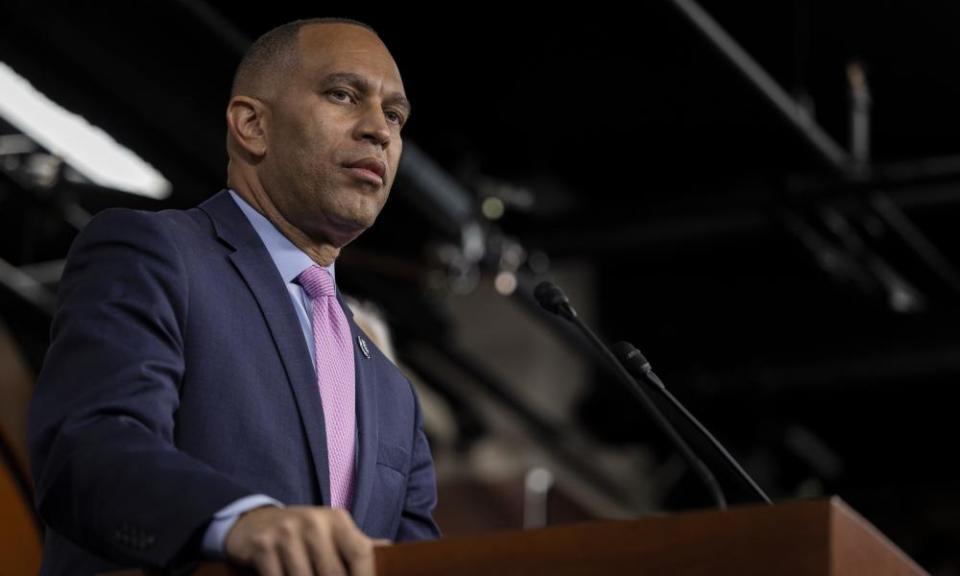

Will the ‘cool, calm, collected’ Hakeem Jeffries change when in power?

Democratic congressman Hakeem Jeffries first emerged in the mid-2000s as a former corporate lawyer homegrown from central Brooklyn. With his focus on criminal justice reform and housing affordability, he was seen as a progressive of the moment who took on the existing Democratic machine in New York.

Now, as the newly-elected successor to House speaker Nancy Pelosi, Jeffries has graduated from state politics to the national stage with the opportunity to make an impression on American politics for years to come.

Last week Jeffries, 52, became the first Black leader of either party in Congress. Under the incoming Congress, Jeffries will be House minority leader, making him the most powerful Democrat in the House. His ascension, paired with the departures of longtime and elderly Democratic leaders like Pelosi, Steny Hoyer and Jim Clyburn, signals a shift for Democrats toward a younger, more diverse generation of leaders that will undoubtedly face tension with a new Republican House majority on the horizon.

Related: House Democrats elect Hakeem Jeffries as first Black leader in Congress

But will Jeffries change? Some political historians argue that Jeffries’ rise fits into a pattern of Black lawmakers who, as they rise the party leadership ranks, become more moderate, raising questions as to how Jeffries will navigate the post differently from his predecessor, Nancy Pelosi.

Katherine Tate, a political science professor at Brown University and author of the several books including Concordance: Black Lawmaking in the US Congress from Carter to Obama, says it was “wise to elevate younger members right now” to energize young voters but questioned whether Jeffries would accomplish anything “radical or significant off the bat”.

She noted that Jeffries will have to navigate competing ideologies not just within his own party, but with a seriously fractured Republican party controlling the House in the next Congress. Faced with his own party’s divisions – including a highly visible progressive wing influenced by fellow New Yorker Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez and her “Squad” – and the chaos of the Republican party’s emboldened extremists, the next two years are likely to be messy.

Jeffries “is not going to have his own agenda. He’s going to shepherd other people’s agendas through”, Tate said.

Congressman Ritchie Torres, who represents the south Bronx, told the Guardian that Jeffries’ rise reflected the strength of his ability to work as an insider and outsider. He described the fellow New York Democrat as “highly cerebral” and “cool, calm, and collected”– capable of talking about the intricacies of policy while quoting Biggie Smalls during former president Donald Trump’s impeachment proceedings.

Torres expected, under Jeffries’ leadership, the Democratic party would be more committed to issues of racial equity, ensuring people of color a seat at the table, even as Jeffries manages and responds to the ideological forces within his party.

Jennifer Garcia, an assistant professor of politics at Oberlin College, agreed, noting that Jeffries’ platform can be an empowering force for not just lawmakers of color but also voters. “Racial identity does matter and because of that, he will behave in a distinct way than past speakers,” said Garcia, who is writing a book on how Black Congress members use legislation to advance policy priorities for Black Americans.

Related: Democrats get Trump tax returns as Republican House takeover looms

Torres says Jeffries is also “willing to reach across the aisle in the service of progressive change”, pointing to his colleague’s efforts in negotiating the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which passed in the House but failed to make movement in the Senate. “He knows how to build coalition and consensus over the caucus, and he’s the best communicator in the House Democratic caucus,” he says.

Analysis by Voteview, a database of congressional votes from the University of California, Los Angeles’ political science department, shows that Jeffries, a member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus and of the Congressional Black Caucus, has a more moderate voting record than some of his older, more liberal Black legislators such as congresswomen Barbara Lee and Maxine Waters. Still, according to Voteview, his voting record remains more liberal than 85% of the Democratic party.

Torres pushed back against any idea that Black lawmakers become more moderate as they rose the ranks, pointing to Black leaders like Elijah Cummings, John Lewis and Jim Clyburn, who is expected to let go of his long-held position as the number three Democrat. “These people are not only progressive but they are also effective at advancing progressive agenda which Hakeem has done,” he says, adding: “Neither the new guard nor the old guard are a monolith. The House Democratic caucus is by and large unified around a progressive agenda.”

Tate said Jeffries came up at a time when the Democratic Party was more open to Black leaders, enabling him to develop the mindset of working across the party and compromising rather than working outside the party. Garcia cautioned that the Voteview numbers were imperfect because it focused on roll call votes on legislation that makes it through hurdles to eventually make it to vote.

“Regardless of race and gender, as you rise in the ranks of party leadership, there’s adapting you have to do to attain that power,” Garcia says.

***

Lupe Todd-Medina, a longtime adviser who worked on Jeffries’ campaigns, described Jeffries as a loving parent with a strong work ethic, and also spoke to his ability to work across the aisle. Jeffries, who has been described as “Brooklyn’s Barack Obama”, grew up in Crown Heights, now a rapidly changing neighborhood in Brooklyn, at the height of the crack cocaine epidemic and escalating crime in New York City.

Related: Fight to vote: the woman who was key in ‘getting us the Voting Rights Act’

One of the few Black attorneys at the law firm Paul, Weiss, Jeffries was part of a class of eventual Black power brokers in the mid-2000s – alongside current New York attorney general Letitia James, state senator Kevin Parker, and now Mayor Eric Adams – who were then considered young progressives out of central Brooklyn. “Those guys were not waiting for their turn,” Todd-Medina says. “It brought a liveliness and rebirth to local politics.”

As a member of the New York state assembly, Jeffries worked with then-state senator Eric Adams to pass legislation to force the New York police department to stop maintaining a database on who was stopped and frisked. In 2018, six years after he was elected to Congress, Jeffries, despite opposition from fellow Democrats, worked with the Trump administration to write and pass the First Step Act, a federal prison reform bill.

“He’s pragmatic. There’s nothing wrong with being pragmatic. There’s no purity test in being that,” Medina says. “You have to be realistic and work across the aisle and he’s always been one to know how to maneuver that well.”

When Black lawmakers first entered a segregated Congress in the 1950s, their policy priorities were ignored by the Democratic establishment, Garcia and Tate said. Adam Clayton Powell Jr, a Black pastor who represented Harlem in the House from 1945 to 1971, was outspoken about how the Democratic establishment silenced him. He would introduce what was known as the Powell amendment to legislation to effectively stop federal funding toward initiatives that perpetuated segregation, Garcia said.

“The Democratic party of the time won’t take up his agenda item. He continues to add it to everything he can. He can’t go through the traditional structure, he had to be a disruptor. People got pissed at him,” Garcia said. “They had to agitate to make themselves the force to be listened to or else they were easily ignored.”

During the Reagan era, as more Black lawmakers ascended to political power, they were concerned Democrats were moving “too far to the right”. During the Clinton administration in the mid-1990s, when Republicans took control of the House, “this put pressure on Blacks to be more unified for the party,” Tate says.

Today’s Democratic party is more liberal and diverse than before, and Jeffries’ ascension to House leader, along with Massachusetts congresswoman Katherine Clark and California congressman Pete Aguilar, reflected a significant generational shift in leadership ahead of a Republican-controlled House for women and people of color.

“We will have to collaborate with Republicans to pass legislation for the good of the country and at the same time, we have to resist the worst of the Republican congress. There’s no contradiction to the two goals,” Torres says. “We will collaborate with Republicans when it benefits the country and we will resist Republicans when Republicans seek to do harm to the country.”

In this atmosphere, Garcia said Jeffries’ impending leadership is “clearly a positive step and important symbolically to empower Black and brown communities” adding: “I’m optimistic that there’s something about him that will take the responsibilities differently than past legislators.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies