After controversy and lawsuit, final LR5 spending report blasts ‘inappropriate’ decisions

The auditing firm that performed a controversial deep dive into a Midlands school district’s finances raises questions about a 2008 bond referendum in its final report.

Released after a specially called school board meeting last week, the report of the Jaramillo Accounting Group highlights problems it found with how Lexington-Richland 5 went about about managing the $234.6 million worth of new school projects that voters approved 15 years ago.

The final report from the New Mexico-based accounting firm hired last year comes as other controversies continue to swirl around some of the firm’s previously announced findings, including allegations about a former superintendent and a company hired to manage construction of an elementary school.

Among issues raised about the bond referendum was that the question posed to voters in 2008 was vague. The question broadly authorized costs associated with constructing, renovating and improving area schools, but didn’t break down the price tag for individual projects.

Instead, the report references a “yellow flier” that was mailed out by the district to residents ahead of the 2008 vote, which broke down the dollar amounts of different projects planned.

“Voters may rely on such communications for their understanding of the intent of the bond referendum, and therefore it could be argued that voters could have been misled if there were material deviations from information disseminated in the Yellow Flier.”

But, as in many such broad multi-project plans, individual projects did not stay within the bounds initially expected. “In our review, we noted certain significant changes to the scope of projects, and associated budget adjustments at the project site level,” the report says.

In all, there were increases in the scope of projects at all four district high schools, totaling $56,422,701. That includes transferring $24.1 million initially allocated for a new elementary school that was never built.

“As it was communicated to voters in information surrounding the bond referendum that a new school would be built, and not these other significant individual projects, it could be argued that a voter may have changed their vote if presented with the above information.”

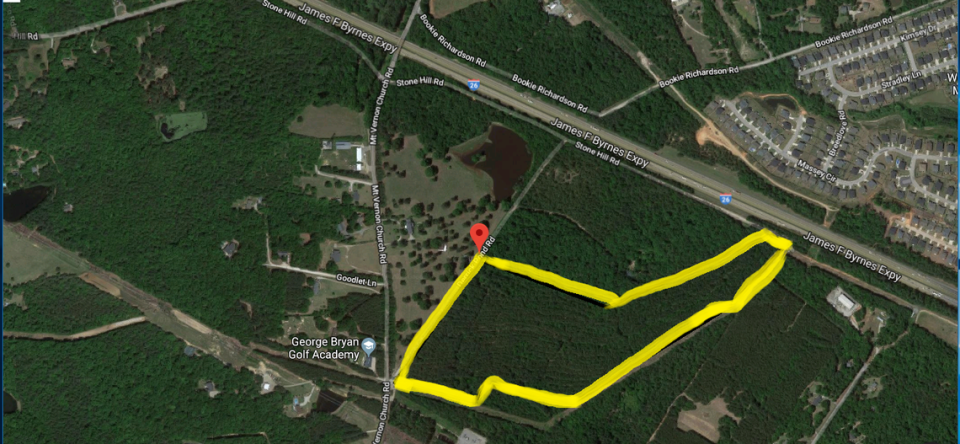

The school district spent $1.2 million acquiring a 47 acres off Derrick Pond Road for an elementary school, but was then unable to acquire the right-of-way needed to connect the property with an adjoining roadway. After abandoning any hope of using the site, the school board voted to sell it in 2021.

Other projects that received bond funding were a new Chapin High School gym ($13.3 million), a field house at Dutch Fork High School ($16.8 million), and the Irmo High School Fine Arts Center ($25.8 million). The report flags these as projects not included in the referendum documents.

The report stresses that the accounting firm doesn’t give legal advice on the appropriateness of any actions.

“The determination of whether a particular bond referendum is misleading is a factual determination that only a court can decide,” the report says.

Jaramillo recommend that “the District implement more rigorous capital budgeting controls, and that the District be more granular in what is considered a budgeted ‘project,’ as a school site taken as a whole is not necessarily a ‘project.’”

“We recommend that the District provide a certain level of detail in bond ref (as these should not be overly broad), and to provide a list of ‘alternate’ projects to voters during the leadup to the election, as this would allow the District some desired flexibility.”

The report also notes $1,175,647 in legal services ended up being charged to referendum funds. Many are related to wetlands mitigation efforts, the report says, but it also says “inappropriate charges” were made for attorney calls with board members, the “request and withdrawal of (an) ethics opinion,” and the “effect of Trustee Kim Murphy’s election.”

Murphy was a school board member from 2010 to 2013, when she was ejected from the board when it was determined she lived in the wrong county.

Because Lexington-Richland 5 straddles both counties, some board members are elected at-large from Lexington County and others are elected from Richland County. Murphy was elected from Richland County but the board later determined she lived in Lexington County.

As a board member, Murphy was sued for blocking construction of facilities at Chapin High School that were included in the referendum. She also engaged in a lawsuit against the district after her fellow board members voted to remove her. The state Supreme Court ultimately upheld the school board’s decision to remove her.

The report questions “whether or not some of these expenditures should have been paid for with taxpayer funds at all, as they appear to be political issues between certain board members and Kim Murphy,” the report reads.

SC school board members accused of illegally meeting at Waffle House

Other issues uncovered by the report included an apparent payroll error that indicated an unidentified bus driver received a salary of more than $1 million. Jaramillo concludes the error was the result of someone entering payment information into the system incorrectly, and that the $1 million was never paid. The report recommends the district upgrade to new software.

Lexington-Richland 5 has agreed to implement some of Jaramillo’s recommended changes, including creating the position of an internal auditor.

While this report focuses on new issues and recommendations, previous reports into Lexington-Richland 5 by the New Mexico-based accounting firm have drawn fire for some of their conclusions.

The Jaramillo Accounting Group submitted a partial summary last September of its audit of spending in Lexington-Richland 5. That report largely focused on criticism of Contract Construction Inc. for its work building Piney Woods Elementary School, which opened near Chapin in the fall of 2021.

The prelimianry report alleged Contract Construction made unauthorized changes to billing for work done on the Piney Woods site, and it questioned the legitimacy of some of the spending decisions made by the company.

The Irmo construction firm hit back at that report, calling it “an opinionated, derogatory, and many times erroneous account.” The company said Jaramillo’s report reached conclusions based on mathematical errors and an apparent misunderstanding of how the contract for the project was approved and structured.

“When we did our own audit of the information we provided JAG, (the audit report) was riddled with errors throughout,” Contract Construction President Greg Hughes previously told The State. “I created a spreadsheet to try to get to the bottom of it, and as far as I can tell, it’s just strictly careless errors. . . . Really it’s just adding numbers up. You could have done that easily.”

Last week, former Lexington-Richland 5 superintendent Stephen Hefner amended a pre-existing lawsuit against the school district to include as defendants Jaramillo Accounting Group as well as school board member Catherine Huddle and former school board members Jan Hammond and Ken Loveless.

He accuses the three board members of conspiring with the accounting firm to retaliate against him because he filed a complaint with the district’s accrediting agency.

‘Turmoil and turnover’: How politics might be causing Midlands superintendents to leave

Jaramillo’s report accuses Hefner of improperly awarded a “sole source” contract to an architectural firm when he was superintendent in 2016. A sole source contract can be awarded if a firm is the only company that can provide a service. Hefner responds that not only was the district aware of the contract, but the school board unanimously voted to approve it.

The latest report released by Jaramillo doesn’t revisit the Hefner or Contract Construction claims from its previously published findings.

Hefner’s lawsuit alleges that Loveless, in a May 3, 2022, email to both JAG and Huddle, “appears to have personally authored the baseless and defamatory statements regarding Dr. Hefner that ultimately appeared in the JAG report.” Loveless, Huddle and Hammond “improperly used their positions of power and public resources to unlawfully conspire with JAG during its investigatory audit,” the lawsuit says.

A court filing by Hefner attorney Billy McGee shows Loveless emailing Jaramillo on June 17 adding “legal” and “sewer taps” to the report. The district’s purchase of unused sewer taps for $178,750 during Hefner’s time as superintendent was ultimately cited in a previous report by Jaramillo as a “significant waste of taxpayer money.”

In another example from July 7, Loveless again emailed Jaramillo saying he wants the report to include procurement violations and misspending from the 2008 bond referendum, with attachments. “This should be where you might start to look,” he said.

Hammond and Huddle previously denied to The State that their actions were improper.

“I am disappointed that Mr. Hefner is attempting to bring me into this lawsuit personally when my actions have always been within the scope and course of my official duties as a school board trustee,” Huddle said in a statement over email.

“That accusation is totally and unequivocally false. I have always worked to protect the integrity of School District 5 and do what is best for every student. I have no idea what Dr. Hefner’s accusations are based on,” Hammond said via text message.

A freedom-of-information request to Lexington-Richland 5 shows that the district has spent $142,150 on Jaramillo’s work as of March 1, with another $19,313.50 in outstanding invoices and approximately $35,000 from other anticipated charges.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies