A contentious meeting, but at least Miami-Dade schools chief search to be more transparent | Editorial

At one point during the Miami-Dade School Board meeting to discuss the next step in hiring a new superintendent, Chair Perla Tabares Hantman said she would not want to be a candidate vying for the job, given the board’s more than five-hour contentious discussion.

“I’d not want to be superintendent under this cloud,” she said referring to the criticism the board has faced.

Tabares Hantman might be right, but the School Board has made its own bed. It went into Tuesday’s special meeting under a cloud of suspicion that the rushed selection of Alberto Carvalho’s successor already is a done deal. To their credit, board members added transparency to the search, but not without bickering and an attempt by Vice Chair Steven Gallon to sidestep the process and nominate the board’s rumored favorite — former district executive Jose Dotres — without any public appearances.

In the end, the School Board landed on a set of next steps that can restore some of the public’s faith. They agreed to invite the top three of 14 applicants (two of the 16 original ones have dropped out) to interviews during a special public meeting. The questions will be drafted with input from community stakeholders, and the candidates will be asked to refrain from listening to the other interviews.

The three finalists are Dotres, now deputy superintendent at Collier County Public Schools; Jacob Oliva, senior chancellor of the Florida Department of Education’s Division of Public Schools; and Rafaela Espinal, an assistant superintendent for the New York City Department of Education. A total of seven candidates met the requirements the board set about two weeks ago.

Conducting public interviews is the right move, for the sake of transparency and optics. Board members spent good part of Tuesday’s meeting ensuring the public they have done their “due diligence” in researching and talking to the candidates and decried “false narratives” that the search wasn’t properly done. But taxpayers, parents, students and teachers deserve to learn more information than what’s in the candidates’ sterile resumes and letters of intent uploaded online.

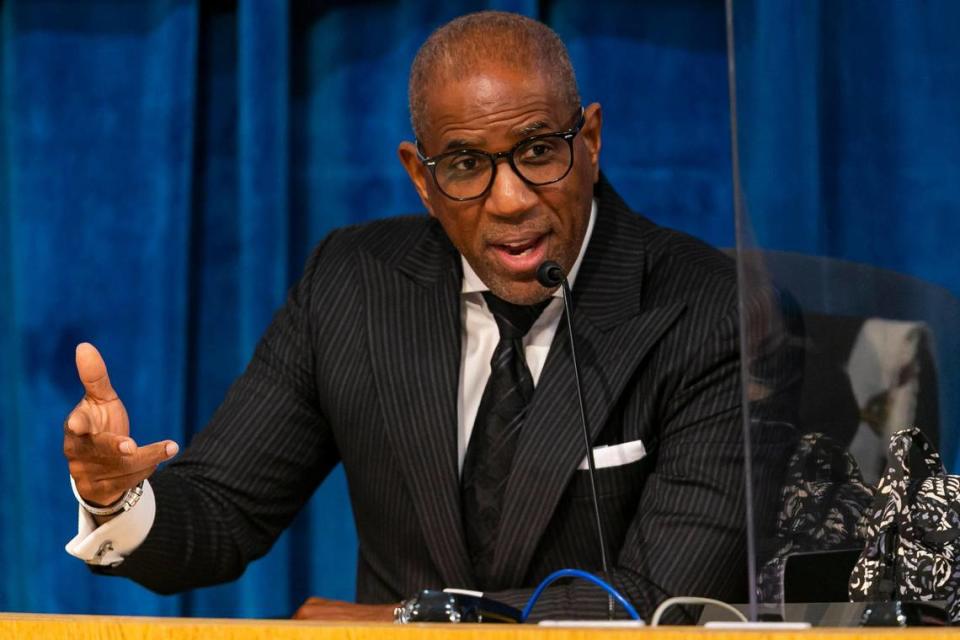

Gallon said he’s concerned that exposing the candidates to a public interview could open a “Pandora’s box” and there’s a “sense of urgency” to pick someone to lead the nation’s fourth-largest district during a pandemic that has been marked by acute learning losses. He said Dotres, who used to be the district’s chief human capital officer, understands the different communities within Miami-Dade — like the difference between Miami Gardens and Opa-locka. But Gallon’s attempt to nominate Dotres after the board had already voted to conduct public interviews angered other members like Lubby Navarro, who called the move “disingenuous to the majority of the board.”

Gallon told the Herald Editorial Board that he spent the weekend interviewing all 14 candidates and he “had that level of conviction” in Dotres after those talks.

“I don’t have that need to go through that exercise again,” he said, adding that he believes this year’s process has been more transparent than Carvalho’s nomination in 2008. In the end, Gallon withdrew his motion to appoint Dotres and followed the “will of the board” in voting for the public interviews after the members ironed how that’s going to work.

We agree with Gallon’s sense of urgency, but the board’s actions over the past few weeks look more like a rush, and if a candidate cannot withstand the heat of a public interview, they’re not fit to lead a district of about 400 schools in a fraught political environment like Miami-Dade’s.

Dotres could indeed be the right choice given his experience and knowledge. But it’s also possible that Oliva and Espinal could woo the board and the community, and they deserve the fairest shot possible. That’s what job interviews are for. The problem, as the Herald Editorial Board has said from the beginning, is the process, not the candidates. Remember the fiasco that was the city of Miami’s hiring last year of a police chief who wasn’t vetted publicly.

The superintendent application period lasted only seven days, and School Board member Christi Fraga said that wasn’t enough time for qualified internal candidates to apply. If she’s correct, we wonder what the district could be missing out on. The application deadline was last Wednesday, meaning the board has had less than a week to screen the candidates.

The upcoming interviews make a process that got off on the wrong foot more credible. But at this point, we can only hope that it’s an earnest effort to screen the finalists and introduce them to the community, and not an empty gesture to appease critics.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies