Colonial Pipeline paid a $5M ransom – but will that only invite other malware hacks?: 'If the payments stop, the attacks will stop'

The reported ransom payment by a beleaguered U.S. oil pipeline company to cyber hackers may spur even more criminal malware attacks on critical U.S. targets, according to cybersecurity experts, and could fuel calls for a ban on such payments.

The critiques stem from a decision by Colonial Pipeline, a gasoline delivery company, to pay more than $5 million for control of its computer system from a criminal syndicate known as Darkside.

“The time has absolutely come for governments to consider prohibiting ransom payments,” said Brett Callow, a threat analyst with the the security firm, Emisoft. “If the payments stop, the attacks will stop.

“The alternative is that our health care systems, critical infrastructure, local governments, schools and other public and private sector bodies continue to targeted with an ongoing bombardment of financially-motivated cyberattacks.”

“I personally believe that part of the reason there is a thriving market and eco-system for ransomware is that people are paying,” agreed Michael Daniel, who served as President Barack Obama’s cybersecurity coordinator with the National Security Council. “Now, it’s a national security and safety threat. And the Colonial Pipeline example makes that abundantly clear.”

The price at the pump: US gas prices rise as Colonial Pipeline reopens after ransomware attack

That perspective was not unanimous, however. Industry officials and some cybersecurity experts contend that outlawing cyber ransom payments could be disastrous if hackers hit hospitals, law enforcement or other critical services – and might push them to do exactly that.

Moreover, they say, in cases where criminals have completely hijacked computer operations the victims have little choice: A refusal to pay could jeopardize lives, damage vital services and destroy the business.

Eric Cole, a security expert with Secure Anchor Consulting and author of the forthcoming book, "Cyber Crisis," said prohibiting ransom payments would force malware victims deeper into the shadows, and they'd still have to pay. “If the government starts making it illegal, it’s going to be like drugs. It’s just going to raise the price of ransoms,” he said.

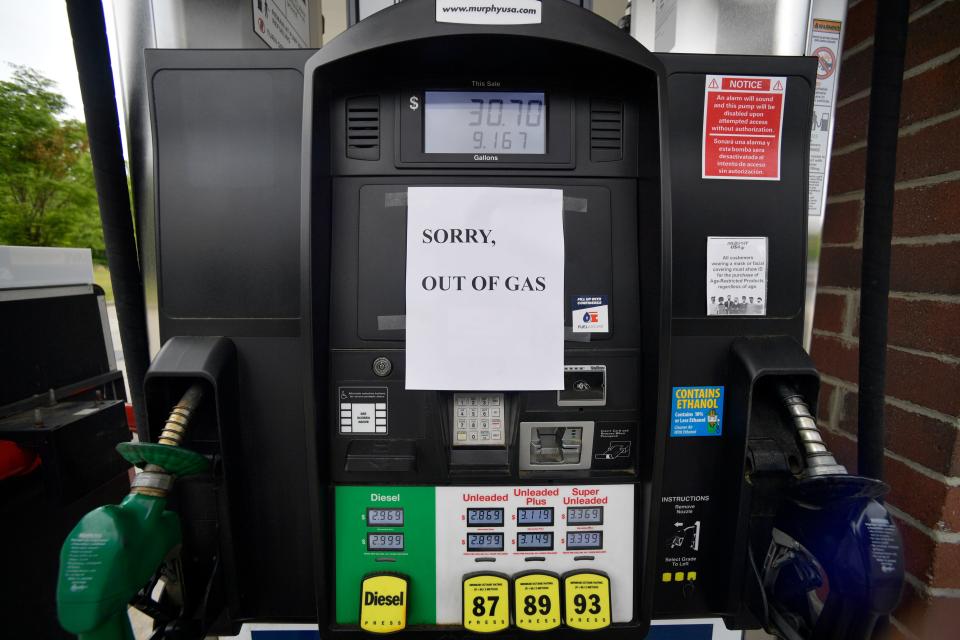

Colonial Pipeline declined comment for this story, but that dilemma —pay or suffer — played out dramatically this week as gasoline consumers went on a panic-buying binge that drained hundreds of service stations.

In ransomware attacks, crime syndicates using malicious software infiltrate a victim's computer system and encrypt the contents. They then demand cash — typically untraceable cryptocurrency — for a code to unlock the data. If the money is not paid, the victim has no access to crucial data or operations, and the criminals may carry out sabotage or publicly release sensitive information.

Colonial was forced to shut down a pipeline system, which provides about 45 percent of gas on the East Coast, according to the Washington Post.

Shortly before the company paid a toll, Cole noted, Darkside issued a statement declaring, “Our goal is to make money, and not creating problems for society," with an implication that it could wreak even more havoc.

The grim options were to pay up or face disruption and possible sabotage during a month’s-long recovery effort, Cole said. "And that ends badly no matter how you play it out.”

Malware criminals ‘run amok’

In congressional testimony just days before Colonial Pipeline was attacked, Christopher Krebs, former director of the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, warned that malware attackers “have been allowed to run amok” and are proliferating because their crimes are so lucrative.

“By paying the ransom, the victim is validating the business model and essentially making a capital contribution to the criminal, allowing them to hire more developers, more customer service,” Krebs noted. “And, most worrisome, go on to the next victim.

“To put it simply, we are on the cusp of a global pandemic of a different variety, driven by greed, an avoidably vulnerable digital ecosystem, and an ever-widening criminal enterprise.”

Other cybersecurity experts said the decision to pay a ransom encourages not only Darkside but other criminals to launch malware attacks.

Daniel said a ban on ransom payments — making them illegal — would give companies a tool to resist demands. But he and other experts acknowledged there is little chance of such a measure making it through Congress due to resistance from politically powerful industries that oversee most of America’s critical infrastructure.

Colonial delivers more than 100 million gallons of gas daily via 5,500 miles of pipelines in 14 states.

Numerous media outlets this week reported the $5 million ransom payment shortly before Colonial announced online that it has resumed delivery to customers.

The Transportation Security Administration, which is the federal lead for oil pipeline safety, did not respond to questions from USA TODAY but provided a statement saying the agency oversees companies by assessing their “voluntary adherence” to federal guidelines.

Colonial Pipeline cyberattack fallout: Expect gas shortages to go away by Memorial Day, expert says

U.S. law enforcement agencies oppose acquiescing to demands from cyber hackers, but have no authority to prevent them unless money-laundering violations occur.

President Biden this week responded to the attack on Colonial by issuing an executive order for cybersecurity. It does not mention ransom payments.

A proliferation of attacks

The nation’s critical infrastructure comprises thousands of business and government operations categorized in 16 sectors, including the energy resources that fuel transportation and provides electricity.

Colonial is part of a larger U.S. network comprising nearly 3 million miles of pipelines that transport natural gas, oil, and hazardous liquids.

Threats and attacks on the system are no surprise. In 2017, a Congressional Research Office report warned that U.S. power grids and pipelines are in peril, and “cyber threats to the computer systems that operate this critical infrastructure are an increasing concern.”

Against that backdrop, the U.S. government does not impose minimum cybersecurity safety standard on those enterprises, except for the nuclear industry.

Chris Cummiskey, former under secretary at the Department of Homeland Security and chief executive with a cybersecurity company, said 85 percent of the nation’s infrastructure is controlled by private enterprises, but the government and public have a huge interest in preventing disruptive attacks.

Cummiskey said the industries have successfully opposed mandates for disclosing ransomware attacks or payments.

“When something happens like this with Colonial, there’s no requirement to divulge,” he added. “And you are more likely to be a target because they paid, and maybe the next will be $10 million… I understand why they paid it, but it certainly can result in a proliferation of these attacks.”

'Life-or-death impacts': Colonial hack the latest in rising threat of ransomware attacks

Companies are not required to adhere to practices preventing computer intrusions, or to maintain secured backups of their data and systems. Instead, federal agencies offer guidance and urge industries to voluntarily take precautions against terrorists and malware attackers.

The National Infrastructure Protection Plan, for instance, is “a framework to guide the collective efforts of partners” by establishing “a vision, mission, and goals that are supported by a set of core tenets focused on risk management.”

The National Petroleum Council and American Petroleum Institute did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

An Oil and Natural Gas Industry Preparedness Handbook, issued in 2016, does not mention cybersecurity.

Industry organizations – concerned about liability, public relations, competition and insurance issues – typically shun regulation. Instead, they advocate collaboration, information sharing and best practices.

But Cummiskey and others, who note a dramatic escalation in ransomware attacks and damage, question whether that works.

According to the security firm, Emisoft, 2,354 U.S. companies, government agencies and schools got hit by ransomware in 2020.

A cybersecurity insurance firm, Coalition, recorded a 100 percent increase in the frequency of ransomware attacks among policyholders from 2019 into early 2020.

Still another firm, firm, Sophos, surveyed about 5,000 IT decisionmakers in 26 countries last year. More than half reported ransomware attacks in the prior 12 months.

Sophos contends that paying a ransom actually increases the cost of overcoming a malware attack. The company found that recovery costs averaged $1.4 million for victims that paid a ransom, but $730,000 for those that refused.

Indeed, perpetrators no longer need technical skills to launch ransomware attacks because expert criminals sell their hacking services online, setting up novices for a cut of profits. Last year, two-thirds of the invasions studied by one cybersecurity firm were orchestrated by those ransomware franchising specialists.

To pay, or not to pay?

Earlier this year, the nonprofit Institute for Security + Technology issued an 81-page Ransomware Task Force report with dozens of recommendations on how to combat malware.

The baseline finding: Most of the world's critical infrastructure organizations “lack an appropriate level of preparedness to defend against these attacks.”

Daniel, a co-chair on the Task Force and chief executive with the Cyber Threat Alliance, a coalition of security companies, said every group working on the report wrestled with whether governments should outlaw ransom payments.

Fact check: Colonial Pipeline gas shortage was result of cyberattack by hackers

Proponents argued that criminalizing the practice would eliminate a motive and reduce finances that allow crime syndicates to flourish. “A further argument is that ransom profits are used to fund other, more pernicious crime, such as human trafficking, child exploitation, terrorism and creating weapons of mass destruction,” the report says. “When viewed in that lens, the case for prohibiting payments is clear.”

Opponents contended that a ban on ransom payouts would push criminals to go after even more essential targets, such as hospitals, forcing victims to choose between payment and widespread upheaval. (In fact, scores of U.S. hospitals have been hit by malware attackers in the past two years.)

Ultimately, Daniel noted, the Task Force punted on the issue of anti-ransom laws — the only policy issue where there was no consensus.

Instead, the Task Force decided payments “should be discouraged as much as possible,” while also calling for regulations that would require victims to report ransomware attacks.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Colonial Pipeline cyberattack: Should ransomware payouts be banned?

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies