'C’mon. That stuff isn’t real': What it's like to suffer from dissociative panic attacks

Editor’s note: In October 2018 Yahoo Canada published a series on anxiety, which is currently the leading mental health issue in Canada. We’re re-running several stories for Bell Let’s Talk Day to help raise awareness and funds for mental health initiatives across Canada.

In Sept. 2017 I was traveling alone for work on a flight to Shreveport, La. when I had my first dissociative panic attack.

I had never been a nervous flyer. I boarded the plane, took my seat and settled in for what would hopefully be hours of blissful in-flight entertainment courtesy of a low-rated Rotten Tomatoes romantic comedy.

Less than an hour into the flight, it felt as though an invisible switch had been flipped. I went to adjust my seat belt and looked down at my hands in my lap. Suddenly they felt as though they didn’t belong to me. I studied them and felt the panic begin to rise. I looked around the plane and watched the other passengers, overcome with a feeling that they weren’t really people, but something else. Actors? My imagination? My heart was racing but I couldn’t move. Nothing around me seemed to be real and I was paralyzed with fear. When the flight attendant shuffled past, I heard myself ask for something to drink, but didn’t recognize my own voice. Everything felt far away, beyond my reach; hazy like a dream.

For the rest of the flight I sat frozen, completely terrified. Afterwards I went to collect my luggage, watching my feet move in front of me robotically. I hid in the bathroom, waiting, but I wasn’t sure what for.

I had had panic attacks before, but this felt completely different. I wanted to call my mom or my boyfriend and tell them that something was wrong with me, but I was too afraid. I felt as though I had completely lost my mind. Opening up about my depression and anxiety to the people in my life was scary enough. How could I tell them about this? I’ve struggled with depression and anxiety since I was a child, but I was certain that I had officially gone insane. How much is too much for your family and friends to take?

A few weeks later, it happened again during a meeting, turning my coworkers into strangers. From the outside, I looked calm. Inside, I was panicking. My heart was racing and I couldn’t speak. I looked fine, but I was terrified. It wasn’t long until these feelings began happening multiple times a week. Whenever I left my house to go to work or go grocery shopping, I would begin to feel as though I was dreaming, and I would begin to panic.

One day it happened while I was driving on the highway. I felt myself separating from my body and my hands on the steering wheel didn’t look like mine, and I wasn’t sure if I was awake or dreaming. I was overwhelmed by the desire to prove if I was awake or asleep. What would happen if I went faster? What would happen if I suddenly just switched lanes without warning? Would I get hurt or would I wake up? I was scared of myself – I had never had those feelings before. I pulled over to the side of the road and broke down in tears. It was time I told someone what was happening. It was too much for me to deal with on my own.

ALSO SEE: Are millennials really the anxiety generation?

At therapy, I learned that I was experiencing depersonalization and derealization: forms of dissociative disorders that can be triggered by severe stress. Dissociative disorders affect approximately two per cent of the population, and are typically the result of an intense traumatic event, usually in childhood. To disassociate is to temporarily and involuntarily disconnect from your memories, feelings and sense of who you are. You mentally check out while your body goes on autopilot. You lose chunks of time and have no memory of what happened.

Unlike dissociation, depersonalization involves the conscious feeling of being detached or disconnected from your body and mental processes. You feel as though you aren’t in control of your body or your actions, but are merely just along for the ride, watching someone else live their life.

While depersonalization affects how you feel about yourself, derealization occurs when all of your surroundings including the people and objects in them feel as though they aren’t real.

When I have derealization episodes, it feels like I’m in a movie, or in a play. The best way I’ve heard derealization explained is that it feels like you’re in a video game. Whenever these feelings take over I become panicked which heightens the derealization — which only makes my panic worse.

Before I was diagnosed with the dissociative and panic disorders, I had been going to therapy fairly regularly for six years. Sometimes I would go once a month, sometimes if I was feeling good, every other month. A year ago, my biggest mental health concern was treating my depression. With therapy and medication, I thought I had finally reached a point where I had a handle on things. I wasn’t “cured’” but I was managing.

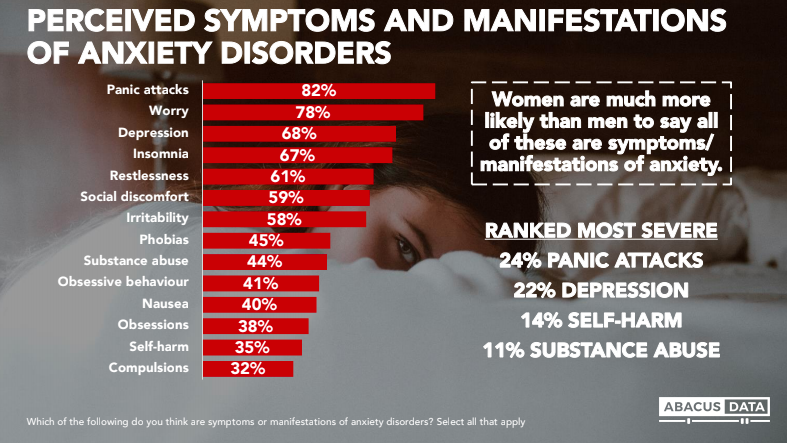

My panic attack last September completely took my feet out from under me. I had never heard of dissociative disorders, nor did I know that it were possible for my feelings to be associated with anxiety – and I’m not alone. According to a national survey conducted by Abacus on behalf of Yahoo Canada, 82 per cent of people associate anxiety with panic attacks. Surprisingly, 68 per cent believe anxiety manifests itself as depression, further proving how entangled the two disorders are in public perception.

I began going to therapy more often, and tried to work on grounding techniques to help me cope with my anxiety. At the time, my benefits package only covered $400 a year in mental healthcare; less than two sessions with my psychologist. I had just bought my first house with my boyfriend a few months earlier. Sure, I was used to paying out of pocket for therapy, but the added appointments combined with a mortgage and a hot water heater that decided to explode was putting a serious financial strain on my wallet.

At the time, I was travelling 20 days of month for work. Being away from home made my anxiety worse. Home was my safe place; everywhere else for me was dangerous. It took a tremendous amount of energy to get up and out of bed, knowing that at anytime when I walked out the door, I could have another episode. I was exhausted and my productivity was suffering.

During a business trip, I sat in the hotel lobby with my boss, waiting for the rest of our coworkers to meet us for dinner. He complained about my attendance at work, and asked me if everything was OK.

ALSO SEE: Nearly half of all Canadians suffer from anxiety — and many believe there’s no cure

I knew I wasn’t performing well at work. Aside from the days I was travelling, I was showing up late for work, or choosing to work from home. Afraid that I would lose my job, I told him that I was going through a hard time. I told him that I was struggling with anxiety and depression, and that I had been for some time.

I’ll never forget what happened next. He finished his drink, put it on the table and said, “C’mon. That stuff isn’t real. Maybe you should have a baby. That way you’ll stop thinking just about yourself.”

I was gobsmacked and infuriated. He proceeded to tell me that mental illness was nothing more than selfishness and something that I could “get over” if I had a family of my own.

When the rest of our party arrived, I excused myself and went back to my hotel room. I wanted to say something to defend myself, to tell my boss how inappropriate his comments were, but I felt like I couldn’t. I was scared that if I said something to my boss, I would be fired. I worried that if I went to Human Resources, it would put a target on my back. I couldn’t afford to lose my job, but I knew that something needed to change.

When I returned home, I knew I had to tell my boyfriend and my family about the panic attacks. It had taken me a long time to become comfortable talking about my mental health with the people in my life, but this was brand new territory for me. I was afraid that my boyfriend would think I had gone “crazy” and leave me. We were just beginning to build a life together and I didn’t want to jeopardize our future. I can’t begin to explain how relieved I was when they told me they didn’t think less of me, and wanted to help me in any way they could to get healthy. When there are people in your life you love you unconditionally, who validate your feelings and will do anything to help you, it makes all the skepticism and doubt from the outside disappear.

With the support of my family and my doctor, I decided to take a leave of absence from work and focus on my mental health. I had always been hesitant to take time off of work, out of fear that I would be seen as “weak” by my coworkers and peers, but things had become unmanageable. I was either going to lose my job or my life; the stakes were that high.

I thought that during my time off, things would automatically get better — but that wasn’t the case. I would still experience derealization any time I left the house. I worried that people were wondering why I was out and about on a random Tuesday afternoon. I wanted to crawl into bed and hide under the covers, and some days, I did just that. Still, I began leaving the house to go hiking with my boyfriend and our dog. I pushed myself to wake up and take a shower every morning, no matter what. I made plans with friends and family, and didn’t cancel – no matter how scared or anxious I was feeling.

When the panic attacks happened, and when I felt myself detaching, I practiced the grounding techniques that I learned in therapy. I would count ceiling tiles, notice details around me, and make a list of things that I knew to be true: My name, my age, my address, my phone number, my date of birth, my hair colour, my eye colour, the colour of my clothes, the names of my family members. I would repeat these details over and over again to bring me back to the present and to anchor me in the middle of the chaos.

I decided that I needed to make a change, and left my job. When things aren’t working, you can either adapt — or move on. It was time to move on. Resigning felt at times like victory, and at times like I was a failure. I was relieved that I would no longer have to travel, but I wondered if I was giving up too easily. I had been there for eight years and I had always been afraid of change – but it was no longer an environment or role that supported me, or allowed me to fulfill my potential.

I began working for Yahoo Canada in the spring of this year. I was nervous to begin a new career path, but for the first time in a long time, I was hopeful. I became part of a team that was supportive and understanding. It mattered that my manager and my bosses were not only sensitive to mental health, but wanted to create content that would help reshape the narrative of mental illness in our society and end the stigma that so many of us face. I had gone from working in an environment that made me feel less-than because of my anxiety and depression, and was now given the opportunity to tell my story to other people, in the hopes that it might bring comfort to someone else, or encourage them to seek help.

Anxiety disorders are complex. This past year has been both trying and humbling as I’ve learned to accept living with depersonalization, derealization and dissociative panic. I wish I hadn’t waited so long to tell my family that I needed help, and that I was struggling, instead of living in fear unnecessarily.

I still deal with dissociative panic, but my episodes are less frequent. I’m still taking medication and go to therapy, but I’ve learned to make my health a priority, and am taking better care of myself. A year ago, I was living in fear of the next panic attack, but now I’m feeling healthier, happier and confident that I can manage the waves of my anxiety.

Dissociative disorders, although not often included in the discussion of anxiety disorders are very real, and nothing to be ashamed of. Talking helps. Talking heals. The conversation of anxiety and mental health needs to include more voices, so that people who feel held hostage to their anxiety know that they don’t have to suffer in silence. Share your story and set yourself free.

Visit the Canadian Mental Health Association for more information on anxiety disorders.

Click here for more information about dissociative disorders.

During the month of October, Yahoo Canada is delving into anxiety and why it’s so prevalent among Canadians. Read more content from our multi-part series here.

Let us know what you think by commenting below and tweeting @YahooStyleCA and follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

Abacus Data, a market research firm based in Ottawa, conducted a survey for Yahoo Canada to test public attitudes towards anxiety as a medical condition, including social stigmas and cultural impacts. The study was an online survey of 1,500 Canadians residents, age 18 and over, who responded between Aug. 21 to Sept. 2, 2019. A random sample of panelists were invited to complete the survey from a set of partner panels based on the Lucid exchange platform. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.53%, 19 times out of 20. The data was weighted according to census data to ensure the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies