Will climate change and a rising ocean mean the end of the road for NC Highway 12?

Laya Barley doesn’t know what she will do this fall if a hurricane blows into the Outer Banks.

Barley is from Buxton, the kind of small town where she knows the middle names of each of the 54 students she graduated from high school alongside this spring, as well as where their grandparents sit during basketball games.

But geography sets Buxton apart, with the Pamlico Sound bordering it to the north and west and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. A single two-lane highway connects the town to the rest of the world: North Carolina Highway 12.

Buxton faces continual threats from hurricanes and nor’easters. Harsh winds blow pounding waves onto or over N.C. 12 several times per year, leaving villagers to fend for themselves. Barley, who will start studying nursing at East Carolina University this fall, doesn’t know what she will do if a storm spins up and threatens the only place she has ever called home.

“Living here, I’ve definitely become more aware of different environmental crises — because I understand myself what living in one looks like and how it feels,” Barley said on a July afternoon without a storm in sight.

The Outer Banks, a string of sand bars and islands on North Carolina’s northeastern coast, is a place of extremes: The midday sun seems more intense on the sand than it does in the city, the ocean next to a beach full of tourists seems a brilliant blue. At night, the darkness is more complete and a visitor can almost hear the silence.

Those attractions draw millions of tourists a year to the Outer Banks, families flocking from Richmond and Harrisburg and Cincinnati to visit the same sun-bleached hotel they’ve been visiting during the same week for the last 50 years. Some of those visitors become residents, retiring to their vacation spot.

But the challenges faced by the Outer Banks are also extreme, borne out of the same proximity to the water that fuels the region’s fishing and tourism industries. Sitting between the Atlantic Ocean and the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds brings threats, with storms punching inlets through the islands from both directions depending on the winds, and sea-level rise pushing saltwater across roadways and into septic tanks.

In September 2000, R.V. Owens III, a one-time member of the N.C. Board of Transportation, told The News & Observer, “Anytime you can ride down a highway and spit in the ocean on one side and the sound on the other, you’ve got problems.”

Farther east than the Bahamas

Hatteras village, near the Outer Banks’ southeastern corner, is about 140 miles northeast of Wilmington, further east than Nassau, capital of the Bahamas. Since 1851, Hatteras has been hit by 156 hurricanes or tropical storms, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with countless other storms and nor’easters sending waves crashing across the Outer Banks.

And when the tide swells, when the ocean is blown inland or one of the flood-swollen sounds shoves its way through the island, N.C. 12 inevitably suffers.

The road runs the length of the developed Outer Banks. It is a crucial engine for the region’s economy and a lifeline for year-round residents of the region’s small coastal towns. Now, engineers, scientists and homeowners are making choices about how to best protect the highway and, thus, the villages it supports.

A handful of flood- and erosion-prone spots along Highway 12 have posed particular problems for local officials and transportation engineers for almost a century. Sea levels in the Outer Banks are rising twice as fast as they are along North Carolina’s southeastern coast and storms are strengthening, heightening urgency among officials to find new answers to an old problem.

The choices facing the Outer Banks are particularly stark, but they are similar to those people in many other parts of the state and country will face as climate change’s effects continue to worsen: At what cost do you maintain homes, businesses and livelihoods in a place that is gravely imperiled?

The highway’s path

A driver crossing the Roanoke Sound from Manteo can turn left on N.C. 12, and head north through tourist-magnet towns of Nags Head and Kitty Hawk, passing mansions built on stilts, ice cream shops and sun-bleached motels before reaching the shrubbery of Southern Shores and Duck and, about 36 miles later, the northern end of the road in Corolla.

Or the driver can turn right, heading south past the Bodie Island Lighthouse and over the Oregon Inlet, onto Hatteras Island.

Most of N.C. 12’s most vulnerable spots are found on Hatteras, be it in the two-mile dune-lined section on the island’s northern end that locals call “the canal zone” or in the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge. The refuge is located on the northern 12 miles of Hatteras Island. It is occasionally split off from Hatteras by the formation of New Inlet, usually due to a storm, creating the area known as Pea Island.

In recent years, the small coastal village of Avon — where more people can be found on the fishing pier on a summer evening than inside a local tavern — has emerged as another of the so-called flooding “hot spots.”

Continuing south, Buxton, population 1,500, is far and away the largest village on Hatteras Island, and Highway 12 shifts directions there, curving toward the west and generally staying on the Pamlico Sound side of the island as it continues on through Frisco.

Between Frisco and Hatteras, the island once again grows so narrow that nothing else can be built, just the road and a dune line next to it.

The land ends just past Hatteras Harbor, but the highway does not, continuing on by ferry to Ocracoke Island — famous for being Blackbeard’s hideout and the spot where he was eventually killed. Then, 13 miles of pavement and another ferry ride later, it crosses onto a short stub on the mainland before ending at the town of Sea Level.

Young people worried about climate change

Evan Ferguson has lived in Buxton for nearly 35 years.

As a high school student, Ferguson opposed the proposal to move the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse to protect it from the eroding coast, worried that the move would damage the historic black-and-white striped structure.

Now Ferguson is a family and consumer science teacher at Cape Hatteras Secondary School, raising her two sons in the same place she grew up. Ferguson’s mother works in the gift shop of the relocated lighthouse, its old location frequently smashed by waves during storms.

Over the last 15 years, Ferguson has become more and more worried about Highway 12 and the stability of living on the Outer Banks. In 2011, some of her students had to reach the school via an hourlong ferry ride after Hurricane Irene washed out parts of the road. Sporting events are often canceled because floodwaters make it impossible to get to or from the school.

“It seems like every couple years something happens now where there’s a breach and our life is kind of thrown out of balance for a little bit where (we think), ‘Gosh, we hope there’s not an emergency — how are we going to get off?’” Ferguson told The News & Observer.

When Hurricane Dorian hit the Outer Banks in 2019, devastating the nearby island of Ocracoke with historic overwash only to be swiftly followed by two disruptive nor’easters, Ferguson was teaching a class called Career and Technical Education Advanced Studies.

Barley, then a student, said the class decided, “Hey let’s get a group together and let’s talk about the climate change and the ocean and what everyone thinks about the island as a whole considering the tide and the hurricanes and how it’s kind of escalating.”

The class sent a survey to all 356 of the school’s students, who range from 6th to 12th grade. The survey intentionally didn’t use the term “climate change,” Ferguson said, instead asking whether kids thought the coast was changing, the sea rising and how long the Outer Banks would be there.

Of the nearly 250 students who responded, 95% said they believe in climate change and 88% said it was causing increased flooding on Hatteras Island. In order for them to keep living on Hatteras, 95% of students said the construction of bridges, buildings and roads like Highway 12 would have to change.

“Our kids are really resilient, but they’re also concerned,” Ferguson said. “I was surprised at how many said that they wanted to move away. However, a lot of them (will) end up staying.”

The class formed a focus group of 15 students — including Johnny Fairbanks, then a high school junior — who delved further into how the road should be managed, presenting their findings to the Dare County Board of Education.

Barley is interested in exploring more terminal groins, jetty-like structures that jut into the sea and keep sand from moving south. She would also like to see more small bridges that run over the island’s most vulnerable spots.

Fairbanks favors a long bridge from Oregon Inlet to Rodanthe, the first village on Hatteras Island. That proposal has been explored — and ultimately rejected — before, but elements of it can be found in how the N.C. Department of Transportation is addressing some of the road’s weakest points now.

The Outer Banks date to the last ice age

Geologists believe that the barrier islands now known as the Outer Banks started forming thousands of years ago.

At the peak of the last ice age, the shoreline was about 50 to 75 miles east of where it is today, sea level more than 400 feet lower. As the ocean started rising, the shoreline moved back.

Then, approximately 5,000 years ago, sea level rise slowed. The sand that was being moved by waves and currents began to pile up, and barrier islands formed. Since then, as sea levels have continued to rise more slowly, waves and current have pushed sand onto and over top of the islands, rolling them west.

That process is still taking place today, said Laura Moore, a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill professor of coastal geomorphology. It is seen in the sand that is swept across N.C. 12 during storms and in the inlets that occasionally burst through, carrying immense amounts of sand.

But human development can disrupt that process, said Moore, who is also director of the Coastal Environmental Change Lab.

This is particularly evident in the long dune line along the Outer Banks, built in the late 1930s and now largely maintained by the N.C. Department of Transportation to protect Highway 12. DOT staff restore these dunes by pushing sand off the road after storms and sometimes by trucking it in from elsewhere.

“When sand is deposited through overwash, that is the land form adjusting to changing conditions,” Moore said. “Every time we reset island elevation by removing that sand, we’re increasing vulnerability as sea level continues to rise. We’re trying to hold the elevation of the island fixed as the sea level is rising around it.”

Vulnerable places

Hatteras Island first becomes visible from atop the Basnight Bridge. As the driver passes far above Oregon Inlet, the bridge crests and the island emerges, a patch of green and tan in the middle of different shades of blue — sea, sky and sound.

Four miles later, the road passes a visitors center in the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge. The two lanes of road right in front of the visitors center are one of the most imperiled parts of Highway 12, NCDOT has determined.

Allowed to continue unabated, erosion of Hatteras Island could reach or cross about a half-mile of the highway at that spot by 2030, and a little over a mile by 2040, according to a peer-reviewed study written by Michael Flynn of the N.C. Coastal Federation and David Hallac, superintendent of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

During a July presentation to a local government task force that is working to find solutions for the highway’s most flood-prone spots, Hallac described his and Flynn’s erosion forecast.

He noted a study led by Florida International University coastal ecologist Stephen Leatherman that found that sea level rise is a relatively small but clear factor in erosion on the East Coast. Higher sea levels, Hallac told the group, means more significant erosion

“It appears we may be seeing that,” Hallac said.

Sea level rise and stronger storms

Sea level rise is just one of the ways that climate change could worsen erosion in some of the Outer Banks’ most flood-prone areas, said Reide Corbett, a coastal oceanographer and executive director of East Carolina University’s Coastal Studies Institute.

The strongest storms that impact North Carolina are likely to grow stronger as the world warms, according to the N.C. Climate Science Report released in 2020. The report also said there is a medium to high chance that wind from hurricanes will intensify in a warming world and the storm surge that hurricanes push toward the coast will be higher.

While sea level rise and the acceleration of sea level rise is an important consideration, Corbett said, “With the changes in climate, we expect changes in storm frequency and storm energy. And so it’s a product of all of that that is leading to changes in the (barrier island) system.”

‘Overwash everywhere’

Like anyone from Hatteras Island, Fairbanks knows all about the flooding.

Fairbanks, who graduated from Cape Hatteras Secondary School this spring along with Barley, knows a storm with northwestern winds is more likely to bring floodwaters rushing into homes and businesses and across Highway 12 in the town of Frisco.

Between the time he was 7 years old until he was 14, Fairbanks and his family saw their Frisco home flood during nine different storms. In 2016, Tropical Storm Hermine flooded the house and then Hurricane Matthew flooded it again, just a week later.

“We just ripped everything out,” Fairbanks told The News & Observer. “Like, everything.”

Fairbanks and his family returned home two days before Christmas. They moved to Buxton less than a year later.

And then there was the time that Fairbanks caught the flu.

He was in ninth grade when he fell ill, and a well-meaning doctor prescribed Tamiflu. Unbeknownst to anyone, Fairbanks was allergic to the medication.

“My whole body was breaking out in rashes and it was just terrible. Plus I still had the flu,” Fairbanks said.

A nor’easter had flooded Highway 12, meaning it was impossible to get to the hospital in Nags Head to treat the reaction. For two days, Fairbanks suffered until the water receded from the road enough that his parents could risk the drive north.

“There was water everywhere,” Fairbanks said. “There was overwash everywhere.”

Under a sunny sky, it would take Fairbanks about an hour to reach The Outer Banks Hospital. On that winter day, with Fairbanks’ body covered in rashes and still suffering from the flu, the drive took three hours.

‘This is home’ but will they stay?

Teenagers like Barley and Fairbanks are deciding now whether they want to build lives on the Outer Banks, knowing fully how flooding can impact daily life.

Fairbanks, who loves fishing and hunting, made his choice a long time ago. He is staying on Hatteras Island.

“I couldn’t imagine trying to leave it,” he said.

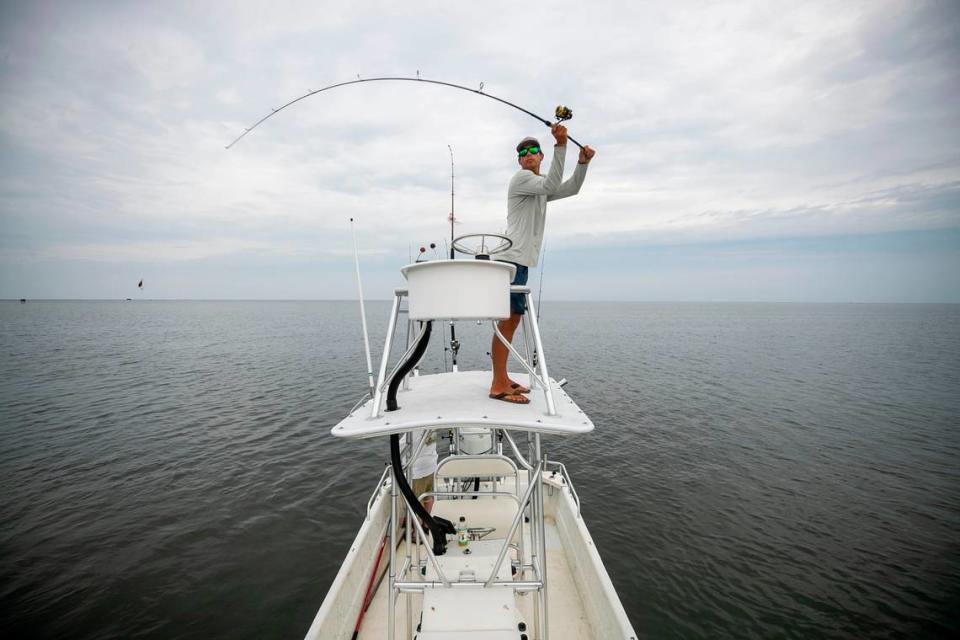

So this spring, before Fairbanks graduated from high school, he earned his boat captain’s license. Fairbanks’ business, Island Time Charters, ran its first trip on June 1.

“I’m here for the long haul,” Fairbanks said. “I think the way Hatteras goes, especially fishing, there’s always going to be something. And I feel like if you do it right, you can always have something to rely on.”

Barley, who is packing her bags and preparing to head to Greenville for at least two years, remains concerned about what the future holds for Hatteras Island.

“It’s scary having to worry about somewhere that you grew up your whole life and you slowly see the water coming up and you slowly see the storms taking more and more with it, and it’s hard making decisions and having to worry about other things other than here,” Barley said.

Barley isn’t sure she’ll come back to Hatteras Island after she walks across the graduation stage in Greenville, possibly as soon as 2023.

“If I find a better opportunity somewhere else, then I probably won’t,” Barley said.

“But this is always home,” she continued. “I don’t think anywhere that I ever move would ever feel as much like home as this place does.”

Reporting for this story was supported by a Southeastern U.S. Ocean and Climate reporting grant from the Institute for Journalism & Natural Resources. This story was also produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund, in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The N&O maintains full editorial control of the work.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies