For these Charlotte artists, COVID was a time of reflection. Now they’re eager to create

For Charlotte’s community of artists, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic brought about all kinds of change.

Some stopped creating and instead took time to process, while others used their period of isolation to focus and expand their reach.

We asked three local artists — Micah Cash, Kalin Devone and Jason Woodberry — how they coped during the coronavirus pandemic, what returning to the studio and their work has meant to them, and what they’re most looking forward to.

Kalin Devone

Working full time as a law office administrative assistant downtown, Devone never worked remotely during the COVID-19 lockdown, so not much changed in her day job. Her art took off, though, and now she’s only there part time.

“This time was really good for creatives,” she said. “People were online shopping, people at home, looking through their social media, so it was a really good time. I have more support than I did before.”

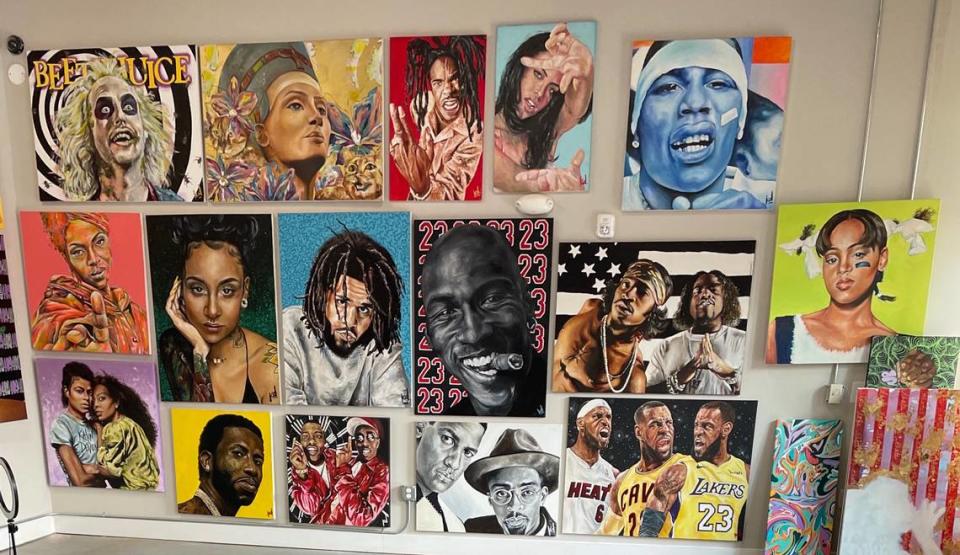

Devone creates vibrant, large-scale oil paintings that focus on the human body. She said her portraits — typically of pop stars and celebrities including LeBron James, Rihanna and Will Smith as The Fresh Prince — examine how social media shapes identity.

“I like being alone, so the pandemic made it easier to be plugged more into myself,” she said.

Around Charlotte, you’ll see her work at the Exchange Business Park as part of Talking Walls, and she assisted artist Sharon Dowell on a mural on Jay Street across from Not Just Coffee that was part of an ArtPop Inpiration project.

“I work with acrylic and oil — the background is usually acrylic, and the portrait part is oil. But I’ve ventured out, especially during COVID,” Devone said. During the pandemic, she has experimented with combining abstract and natural elements in her murals.

Given the scope of her work, space presented a problem.

“I didn’t have a separate studio, so I was just painting at home in the living room,” she said. “I actually had a lot more sales than I normally would, so I expanded and moved into a bigger place.”

These days, Devone works out of a studio as part of an artist residency at The Village at Commonwealth near Plaza Midwood.

During the pandemic, she said her social media exposure increased and her sales doubled. On Instagram, Devone now has over 20,000 followers. “People wanted to shop, and they had money to invest.”

This summer, Devone participated in a program with the Charlotte Museum of History.

“We were given a historical figure from the Charlotte area. There’s no actual image of the people we were given, so we had to interpret what they would look like,” she said. Some of her work was on display in the front of the museum’s lobby.

Devone’s work also has been displayed at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture, in small shops around Charlotte, and at art shows and exhibitions. That includes BlkMrktClt’s Nu Growth Exhibition Series, which featured the work of six local Black women artists.

“I paint so large that people don’t realize the size and the scale. So when they see it in person, it’s a completely different conversation,” Devone said. “I’m ready to interact with people again, one on one. I’m tired of emails and texts.”

Micah Cash

Cash spent spent much of 2018 inside Waffle Houses throughout the Southeast. Following a string of racially charged incidents that occurred at the diners, the artist wanted to more deeply examine the quick-eat chain through his photography lenses.

In late 2019, Cash’s book, “Waffle House Vistas,” a look at social, economic and political divisions through views from Waffle House windows, was published by The Bitter Southerner. Then the pandemic hit.

“By spring, we couldn’t do any promotion outside of virtual promotion, so these photographs from that body of work had only been exhibited locally,” Cash said. He was unable to travel to promote the project or give lectures about it outside of Zoom.

Still, the book is in its third printing and has sold over 4,000 copies.

“The motivation and the momentum behind that project normally would push me to the next thing,” Cash said. “But now, I’m at that place where I’m ready to get back on the road because I can make more photographs for the second edition of that book.”

The former senior manager of individual giving for the Charlotte Symphony Orchestra was able to work from home, but felt devoid of creative energy.

“I shut down during the pandemic,” he said. “After it started, I had no desire to be creative for about a year. There was just too much — too much pain, trauma, fear and uncertainty.”

As a place- and spaced-based photographer, Cash is used to week-long road trips to sites of interest and research for his work. “I missed that,” he said. “I’m really excited to get back to that practice and do some field work.”

About a year later, he got the itch to draw, which led him to apply for one of the McColl Center’s new studio spaces. “I thought, If there’s ever an opportunity for me to kick-start this creative energy, this is it, because it forces me to utilize the space and make it count.”

While his recent studio practice has been largely photography-based, Cash is also a painter and printmaker.

“Part of me being at McColl is to rekindle that side of my practice and make some new paintings and new prints, and have the McColl Center be the headquarters for my travel and photo editing, as I work on my next two book projects.”

For Cash, much of the great art out of the pandemic hasn’t yet surfaced. “There’s just been so much loss, and so many things taken from us. We have to grieve it in many ways.”

Cash is examining the tension between return-to-work policies and how people now value themselves.

“I don’t know how to make art about it yet,” he said. “But there’s something really interesting about somebody who used to work three service jobs now saying, ‘I refuse to work any of those jobs unless you pay me this amount.’ That’s really powerful.”

Cash also spent a week photographing Waffle Houses in Tennessee and Kentucky for the next edition of his book. And he’s deep into research for a future book project about the storytelling and design of theme parks.

“There is also a project centered on the economic and cultural significance of Southern beaches,” he said. “It is time to make some new photographs and find ways to visually engage with these topics. That’s the fun part.”

Jason Woodberry

Woodberry has a lot to say.

The full-time software engineer for Disney spends hours at his art studio at the Hart Witzen gallery, working on ways to use art as a tool to initiate important conversations.

Once recent ongoing collection features Afro-futuristic art that highlights social and political issues. “Intergalactic Soul” was featured at the Gantt in collaboration with Marcus Kiser.

“It’s a sequential narrative about two young Black astronauts, Pluto and Astro, traveling the universe, experiencing metaphors of social and political issues,” Woodberry said of the series. The characters encounter Jim Crow robots and a cereal brand called Kosmic Kulture Krunch (or KKK), he added.

“Marcus and I both grew up heavy into comic books and science fiction,” he said. “Any artwork is just a tool in order to talk about a message and to get conversation built around that message,” he said. “We’re trying to get the conversation started with as many people as possible.”

A recent product of the partnership, Project LHAXX, ran from August 2019 to July 2020 at the Ackland Art Museum at UNC Chapel Hill. LHAXX is the name of a text Woodberry created, inspired by Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose cells were unknowingly used for medical research.

The mixed-media experience blended murals and augmented reality.

“The resulting immersive experience invites us to consider both the forces in society that allow for the absence and erasure of Black cultural histories and also ways in which those losses may be mitigated,” Ackland Art Museum said of the exhibit.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, Woodberry had a lot of time to think.

“Everything slowed down, and you had this moment of historical events from George Floyd and Black Lives Matter to Breonna Taylor,” he said. “For much of that time, I wasn’t really creating, I was reading… especially about being able to talk about your work.”

And because he has lupus, Woodberry stayed put.

“I didn’t really go out much at all,” he said. “I couldn’t work on the things that I wanted to work on because the ideas I had required me to have space, so I journaled my ideas,” he said.

Plants that he started growing during lockdown also provided some comfort. “You need to step outside of yourself and give attention to something else,” he said. “For a while, it almost seemed every day was the same day.”

He missed attending art exhibitions the most. “I want to travel more to see art because that’s a very important thing as an artist,” Woodberry said. “You can’t just lock yourself in a studio.”

Today, he is exploring acrylic paintings, something that’s new to the predominantly digital artist.

“The work is rooted in the idea of anger and frustration, and how to address these emotions,” Woodberry said. “What do you call the thing that possesses you? We name things that we would like to own, have a relationship with, or control, so I’ve been thinking about that.”

More arts coverage

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for the free “Inside Charlotte Arts” newsletter at charlotteobserver.com/newsletters

You can also join our Facebook group, “Inside Charlotte Arts,” at https://www.facebook.com/groups/insidecharlottearts/

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies