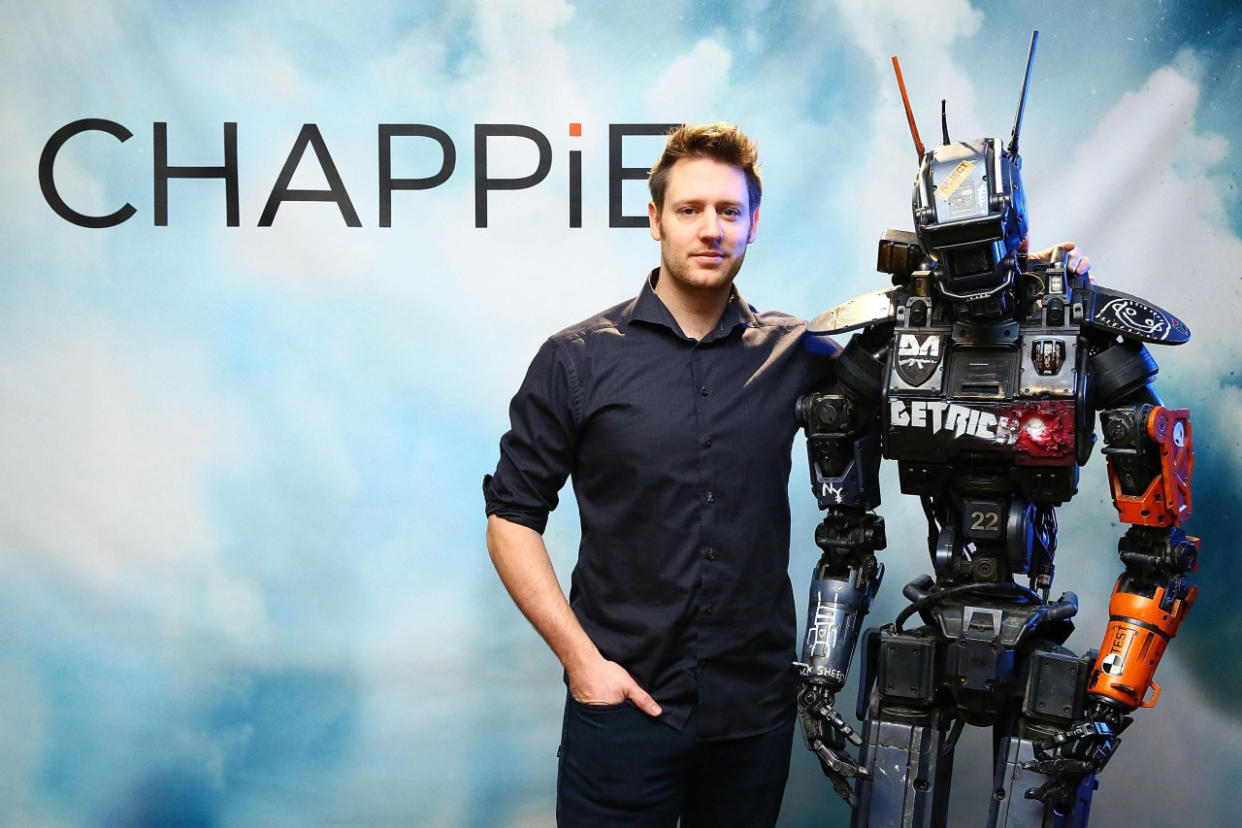

'Chappie' Director Neill Blomkamp is Optimistic About Two Things: Robots and Hugh Jackman's Mullet

Neill Blomkamp, the South African, Oscar-nominated director of District 9 and Elysium, says he views the world in a “very violent and hostile manner.” That point-of-view shows in his films, which generally depict grim futures where the poor live like vermin in bombed-out cities. But Blomkamp shows a glimmer of hope in his new film Chappie (out Friday), which stars Slumdog Millionaire’s Dev Patel as Deon, a genius inventor who creates artificially intelligent robots to serve as police officers in a near-future Johannesburg, South Africa.

Deon’s robot cops — which operate on advanced logic-based artificial intelligence software that Blomkamp refers to as “soft A.I.” — help clean up the city with brute force. The invention makes a fortune for the weapons company where Deon works, much to the chagrin of a former soldier named Vincent (Hugh Jackman), who fears that robot soldiers will eventually replace human beings and is determine to short-circuit Deon’s ambitions.

Then Deon comes up with an even more incredible invention: “hard A.I.,” as Blomkamp calls it, which means an artificially intelligent being that can truly think for itself. The robot, who Deon nicknames Chappie (played in motion capture by Sharlto Copley), is soon stolen by three black-market outlaws (two of whom are played by the hip-hop group Die Antwoord). Emotional development and gun battles ensue, raising plenty of moral and technological questions along the way. Blomkamp recently spoke with Yahoo Movies about the film, his views on artificial intelligence, economic stratification, and Hugh Jackman’s tremendous mullet.

We don’t have robot cops yet, but things are getting more and more automated, whether it’s algorithms that write basic journalism stories to self-driving cars.

Now, you can install a bunch of automated responses to things and then the system will figure out an answer based on pre-meditated lists. In our lifetime, soft A.I. will get to the point where it’s indiscernible from a human — it passes the Turing Test, and you’re not sure what it is. But it’ll never actually be intelligence; it’ll never actually think, ‘This is a new way to harness energy; this is a new kind of airplane; this is how to solve cancer.’ And if it does that, it’s a long way away.

It’s interesting to have a bad guy like Vincent who isn’t necessarily wrong.

He may not be right, though. The Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk “we’re so fearful of A.I.” thing: That could be wrong. Vincent is right or wrong depending on how you feel about A.I. To me personally, I’m not sure A.I. is actually possible. But if it is possible, I’m more optimistic. I don’t think that we’re going to have some kind of Terminator situation, with Skynet hunting us. I think real artificial intelligence is a shift that is unmappable. I think if it happens, there’s life before and then there’s life after; it would literally change the planet.

Despite your optimism, soft A.I. has lots of worrisome implications, like putting people out of work in a lot of different fields.

I think that you’re probably going to see a lot more menial day labor tasks get reduced to zero. I don’t know what effect that will have on the economy though, because you are also freeing up a lot of people to do more interesting things. It’s like the age-old thing: If there’s engineer in Pasadena landing the Mars Rover, there’s probably an engineer able to do that living in the slums of Uganda somewhere — if he ever gets the chance.

Your film Elysium was about the rich living in a utopian biosphere, while the poor had to scavenge on a wrecked Earth. During the press tour, did you find that part of the problem with the response to the film was that Americans don’t like talking about class and money?

America’s just kind of f—-ed up in general. I think that America used to be the most beneficial, important country on the planet that was doing things that no other country could do and was a beacon of everything, like art and engineering and science. And I think what has happened is that greed and mostly corporate power has corrupted the elite in a way that is so extreme that the country no longer serves the interests of the people that live the country and no longer serves the world. I wish America would right itself, because it is capable of being such an unbelievable country, and it’s almost there, but it’s just f—-ed right now.

Hollywood is mostly focused on franchise films these days. Was it difficult to get Chappie made, especially by a major studio like Sony?

Yeah, I had to shed a lot of blood. It’s not easy to make a film like Chappie. Everything has become more corporate — Wall Street has infected all of these different elements of life. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, music to some degree was the anti-establishment. It was the revolution. Music was where you would turn if you wanted to look away from the government and look away from corporate control. Now, you look at music today in the 21st century, it’s the same machine. It doesn’t talk about anything. Even gangster rap sounds so right on the edge, but it’s talking about what it’s allowed to talk about.

And that anti-establishment, that needed thing, is gone in music, gone in film, it’s gone pretty much everywhere. Because everything is [like] a sausage factory making widgets right now that need to return a profit. It’s not really made for the same reasons. That’s depressing. On one hand, I feel very thankful to Sony and MRC [financier Media Rights Capital] because the movie exists. But I also feel like it’s a tough day-to-day process to make a film. So it’s a difficult one to answer. I’m happy that things turned out the way that they turned out.

I’m sure there’s some more extreme version of this movie somewhere in the back of your head.

In terms of it getting messed with, no. That’s why I think I like the movie so much: It feels quite honest. It’s hardly tampered with. It’s very very honest to what I wanted to make.

Most importantly, what inspired Hugh Jackman’s fantastic mullet (shown below)?

I wanted him to be rough around the edges, from an Australian farming family. There was a photo of an Australian kid that I found that I sent to Hugh, and I was like, “Could you do this haircut?” And he was like, “I love that hair!”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies