Cash buys, private flights, changing rules: How Idaho hides from execution oversight

Editor’s note: This story was produced in collaboration with the Idaho Capital Sun and benefited from public records grant funding through The Gumshoe Group investigative journalism initiative.

Last June, two days after a condemned man outlived his scheduled execution date, he made a macabre appeal to the agents tasked with guiding him to his end. Then he made it again. And again.

“The use of pentobarbital at my execution is too risky under the Eighth Amendment,” Idaho death row inmate Gerald Pizzuto wrote to his prison warden on June 4, citing the prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. “My medication history … will make it very painful. The firing squad can be used and would be more humane.”

When his petition was rejected on the grounds that lethal injection is Idaho’s only approved method of execution, Pizzuto submitted his same request in July, and once more in August, according to documents obtained by the Idaho Statesman under the Idaho Public Records Act.

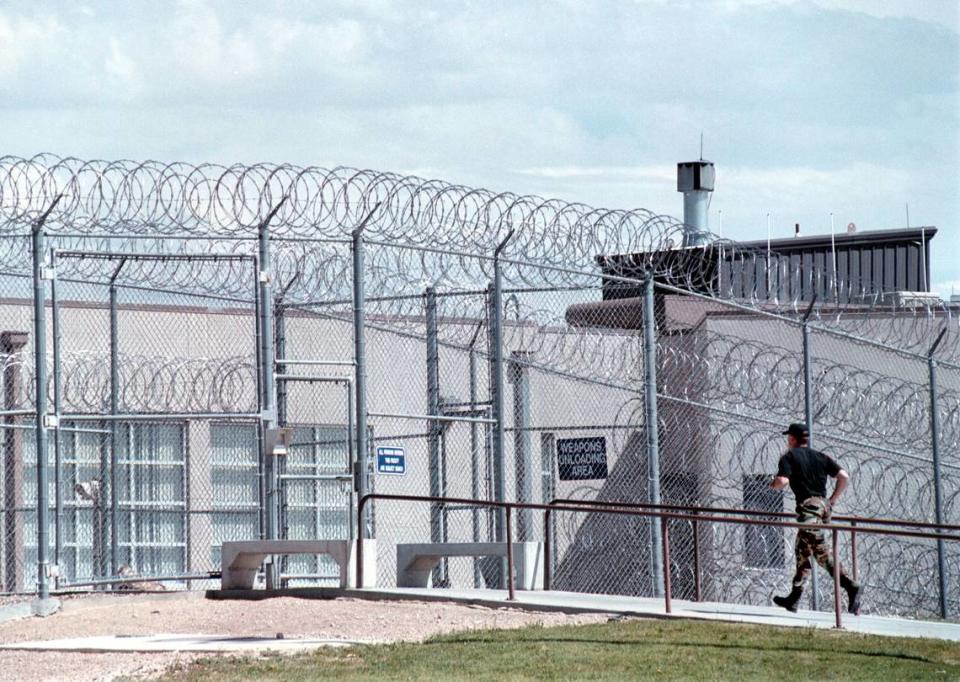

The renewed push to execute Pizzuto, who is terminally ill with cancer, has prompted further scrutiny of Idaho’s history of secrecy around putting inmates to death by way of lethal injection. An investigation into the state’s most recent executions reveals the lengths to which prison officials have gone to withhold documents from the public that disclose their past practices for acquiring the deadly drugs, the associated taxpayer costs and the identity of their suppliers.

Idaho Department of Correction officials continue to decline to say whether they have the lethal injection drugs needed to execute Pizzuto, or name their source for the chemicals. The department’s spokesperson has said only that when the time comes — once a death warrant is issued — the state agency is confident it will have the drugs necessary to carry out the mandated execution.

IDOC’s latest refusal last week follows nearly a decade of department efforts to prevent public release of information about its execution procedures. A series of legal defeats in recent years finally forced the department to disclose records that showed the covert ways that prison leadership operated to conceal any information that could reveal their execution drug sources.

Court proceedings and documents judges ordered released in a public records lawsuit show that in Idaho’s last two executions — Paul Rhoades in 2011 and Richard Leavitt in 2012 — IDOC paid more than $20,000 in cash to acquire the drugs from out-of-state pharmacies in the days leading up to scheduled lethal injections. Experts on the death penalty, civil rights and pharmaceutical law have called such practices — directly involving IDOC Director Josh Tewalt — ethically suspect and potentially risky to the inmate.

Pizzuto’s attorneys with the nonprofit Federal Defender Services of Idaho have gone a step further. They say that the past actions of IDOC officials to acquire lethal injection drugs, including bringing a suitcase full of cash to an alleged after-hours parking lot exchange, border on illegal.

“IDOC’s history of resorting to shady drug sources for its most recent executions makes it more likely that it will happen again,” Jonah Horwitz, one of Pizzuto’s attorneys, said in a written statement to the Statesman. “Using drugs of questionable quality or reliability would be dangerous under any circumstances, and would pose even more of a threat to Mr. Pizzuto because of his grave heart condition and complicated medication history.”

IDOC officials have repeatedly declined to answer questions from the Statesman about lethal injection drugs and suppliers, or the department’s past acquisition practices. They cite IDOC’s recently revised public records exemption rules, as well as active or anticipated legal challenges — including those filed by Pizzuto’s attorneys in state and federal courts.

The experts in their respective fields, meanwhile, say the state’s track record with lethal injection gives them concern over whether IDOC will change course and operate differently with Pizzuto, as well as the other seven inmates on Idaho death row.

“The Department of Correction seems to have very little respect for the law, and certainly almost no respect for democracy and public transparency,” Ritchie Eppink, the American Civil Liberties Union of Idaho’s legal director, said in an interview. “So I have very little faith in the Department of Correction in carrying out this execution properly, and certainly carrying it out transparently in a way that actually brings justice and dignity to our state.”

Pizzuto lethal injection plan garners scrutiny

Questions persist about Idaho’s efforts to block release of drug acquisition information as the U.S. continues to wrestle with the politically charged debate over capital punishment, now as a majority of states no longer permit executions. Last year, Virginia became the 23rd state to abolish the practice, in addition to the standing governor-imposed bans in California, Oregon and Pennsylvania. Washington, D.C., also has in place a permanent prohibition on executions.

Lethal injections in particular have garnered heightened focus in recent years after drug manufacturers halted sales to prisons, making the chemicals used to end inmates’ lives much harder to obtain. The situation has left states like Idaho that still seek to execute prisoners choosing to employ unconventional means and sources to comply with the terms of these decades-old convictions, including Pizzuto’s.

Reports of botched executions in several states have also generated repeat national headlines, drawing the ire of anti-death penalty activists. For example, in a 2015 case in Oklahoma, an autopsy later confirmed that prison officials administered the wrong drug during an inmate’s execution, with the man expressing as his final words: “My body is on fire.”

Oklahoma and Utah are the only states in the U.S. where use of a firing squad is an approved backup method of execution. The option remained on the books in Idaho until 2009, and IDOC considered asking lawmakers to reinstate the firing squad as recently as 2014, but the concept didn’t move forward.

Increasingly under the microscope, capital punishment decision-makers are paying greater attention, too.

Last year, Oklahoma’s parole board recommended several death row inmates’ sentences be reduced to life in prison until the state resolves its lethal injection process. The year prior, Ohio’s governor placed executions on “unofficial moratorium” after a federal district court judge in Ohio ruled applying the state’s lethal injection protocols to a death row inmate would “almost certainly subject him to severe pain and needless suffering.”

Pizzuto’s attorneys have made similar arguments in advocating against his execution.

Pizzuto, 65, has been on death row for more than 35 years. He was convicted and sentenced to death in 1986 for the murder of two people the summer before at a remote cabin in Idaho County, north of McCall. Pizzuto previously served nine years in prison for a rape conviction in Michigan and was also found guilty of two murders in Washington state after his Idaho conviction.

This past May, Pizzuto’s attorneys successfully petitioned the Idaho Commission of Pardons and Parole to grant their client a clemency hearing — just the second for an Idaho death row inmate since the state reinstituted capital punishment in 1977. The unexpected move led to a stay of execution — Pizzuto’s third time sidestepping being put to death since his conviction. That shelved his scheduled June 2 lethal injection.

His attorneys argued that their client’s appalling childhood and fading health, which includes late-stage bladder cancer, heart disease, diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, deserved the board’s consideration of reducing his sentence to life in prison. He has been in hospice care for about two years.

Given Pizzuto’s unique set of serious health issues, his attorneys have stated that the use of pentobarbital — a potent sedative that can stop a person’s breathing in higher doses — violates Pizzuto’s rights against cruel and unusual punishment guaranteed under the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Dr. Jim Ruble is an attorney and longtime doctor of pharmacy who teaches law and ethics courses at the University of Utah’s College of Pharmacy. He has frequently been an expert witness in death penalty cases, and he agrees that the use of compounded pentobarbital in the execution of inmates with complex medical histories invites uncertainty.

“An individual with a lot of compromised organ systems is not as predictable as what we might think,” Ruble said by phone. “How they react to it introduces a lot more variability. It could potentially be much less effective. Because of the complications of their overall health condition, it could also hasten their death, too.”

‘So little transparency’ on executions nationwide

The recent obstacles to obtaining the drugs needed to fulfill death sentences have driven states further into secrecy, said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. The Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit takes no formal stance on capital punishment, but it has been criticized by some death penalty proponents as supportive of anti-death penalty positions.

“This is part of a larger issue when it comes to executions in the United States: There is so little transparency,” Dunham said by phone. “But there should be transparency at each stage. If a policy can’t be carried out in the light of day, then you have to question the policy.”

However, defenders of the policies in question argue that confidentiality is necessary to ensure the state can obtain the drugs needed to follow through on Idaho statute. Lethal injection is Idaho’s only permissible means of capital punishment.

“This is a debate not limited to Idaho,” Jeff Ray, IDOC’s spokesperson, said last year by email. “Across the country and in Idaho, capital punishment opponents have used protests and other means to discourage chemical suppliers from assisting states with carrying out executions. Capital punishment remains the law in Idaho.”

In the process, IDOC has established itself among the group of state prison systems that have tried to prevent release of their past and future execution practices, according to documents obtained through public records requests and court orders, as well as the department’s evolving disclosure policies.

The recently released trove of records shows that IDOC pursued covert tactics to obtain lethal injection drugs from a compounding pharmacy in Salt Lake City in 2011, and another in Tacoma, Washington, in 2012. The chemicals — at that time from sources not known to the public — were then used over a seven-month span in the arms of death row inmates in Idaho’s last two executions: Rhoades, 54, a convicted triple-murderer, in November 2011; and Leavitt, 53, also convicted of murder, in June 2012.

Compounding pharmacies are less regulated, because they are not closely monitored by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The federal agency charged with approving drugs instead defers to individual states to oversee these pharmacies and the drugs they produce.

“This means that FDA does not review these drugs to evaluate their safety, effectiveness or quality before they reach patients,” the federal agency states on its website.

As a result, the pentobarbital prepared in a compounding pharmacy for executions is prone to less reliability, Ruble said. Factor in how the drug is handled, stored and administered after it leaves the pharmacy, and questions remain about the stability and sterility — in other words, the overall safety — of what’s ultimately injected into an inmate.

“There are profound differences between something manufactured commercially and something that a compounding pharmacy makes,” Ruble said. “Just because there’s a compounding pharmacy out there, it doesn’t mean they necessarily have all the understanding of these particular formulations. Some do, but it’s more than just prep.

“What I’m getting at is we don’t know,” he added.

University of Idaho professor’s lawsuit prompts IDOC fines

The bulk of IDOC’s lethal injection documents now available originate from a public records request filed in September 2017 by Aliza Cover, a University of Idaho law professor whose work focuses on criminal law, including the death penalty. She sought documents related to the use of lethal injection drugs in the state’s most recent executions, which IDOC officials largely denied.

The following February, Cover sued, with the ACLU of Idaho’s legal team representing her. The lawsuit, which dragged on for more than three years and involved the Idaho Supreme Court on appeal, eventually compelled IDOC in early 2021 to hand over all the records without redactions that would shield past execution drug suppliers.

During the legal proceedings, judges ruled that IDOC officials had not adhered to the department’s own public record disclosure rules. They also admonished IDOC officials, including then-Deputy Director Jeff Zmuda and Ray, the department spokesperson, for withholding records in bad faith and conduct deemed “frivolous.” Ray was slapped with a personal civil fine of $1,000, and the court awarded Cover more than $170,000 in state funds toward costs and attorneys fees.

In the midst of the lawsuit, however, IDOC moved to tighten its records exemption rules for information related to executions — specifically identifying information of drug sources.

In May 2019, Tewalt led a presentation before the department’s three-seat, policy-setting board appointed by the governor to shore up which documents the agency may keep from public consumption. He suggested changes to execution exemption guidelines “to provide clarity on information that will be disclosed,” according to IDOC Board meeting minutes.

While IDOC continued to defend itself in the Cover lawsuit, Tewalt told the IDOC Board, down to just two members at that time, that the department is committed to transparency concerning executions. During the meeting, he spoke of refining records disclosure rules to limit possible exemptions and what would be withheld from the public, the meeting minutes report. But, in fact, several of Tewalt’s recommended changes would further restrict what the department released going forward, including any information the director exclusively determines could identify the source of execution drugs.

“When a government responds to a problem by hiding the evidence, that should not give anybody confidence that they’ve addressed the problem,” said Dunham, of the Death Penalty Information Center. “That should make the public rightfully indignant and should cause the public to trust the government less. I’m not saying that no state should ever carry out an execution. I’m saying if you’re untrustworthy, you should not carry out an execution.”

The IDOC Board voted to adopt the execution disclosure revisions recommended by Tewalt before the suggested changes went to a joint hearing of the Idaho Senate and House judiciary rules committees in January 2020. Unlike changes to law, these rules require only committee approvals to be implemented — not full votes by the Idaho Legislature.

Through Ray, Tewalt has declined four interview requests from a Statesman reporter over several months, including about the changes to IDOC’s records disclosure rules. But in a November 2021 email exchange between Tewalt and Ray about an interview request later obtained in a batch of public records for this investigation, Tewalt offered greater detail.

“I won’t comment on chemicals and I’m not inclined to revisit the rule issues that were discussed and adopted in an OPEN board meeting AND vetted before the House and Senate Judiciary Committees,” Tewalt wrote to Ray. “I don’t have anything to add beyond what’s been publicly discussed.”

Earlier, Tewalt went before the joint-committee hearing in January 2020 to request support for final approval of his recommended disclosure changes.

“The intent behind the (IDOC) Board’s action here is to try to mitigate things that would jeopardize the department’s ability to carry out an execution,” Tewalt told members of the two committees. “So I would certainly urge your favorable consideration of this particular docket.”

At the hearing, a representative for the Idaho Press Club also appeared and advocated against the two committees sanctioning the proposed exemption changes, citing the ongoing Cover lawsuit with IDOC and “possible erosion of the Idaho Public Records Act” if approved.

“The Press Club has concerns about the dangerous precedent this would set as it relates to other department rules and their handling of public information,” Ken Burgess, an Idaho Press Club lobbyist, told judiciary committee members. “As long as the state engages in public executions as punishment, it is critical that the information related to that execution should also be made public and transparently available.”

The Idaho Senate and House committees each voted to approve IDOC’s recommended changes with limited opposition.

“Our government should not have anything to hide when it comes to the most serious thing that the government does, which is kill a human being,” said Eppink of the ACLU, who was part of Cover’s legal team. “If the way that Idaho is killing people was honorable, the Department of Correction in the state of Idaho would be putting that information on its website. But they don’t want you to know this, because they don’t want the public to understand how outrageous their entire execution process is, including the taxpayer money.”

The total cost of maintaining capital punishment is difficult to determine, based largely on the lengthy legal process afforded to death row inmates who appeal their sentences or convictions. The price of execution drugs also has risen in recent years as supplies dwindled. Several studies have shown that in cases where the death penalty is pursued, states on average spend hundreds of thousands of dollars more in taxpayer funds.

After a district court ruled in favor of Cover, IDOC appealed to the state Supreme Court. The court ignored the department’s disclosure changes in issuing its November 2020 decision and ordered IDOC to hand over all nonexempt records to Cover. The formal order took effect in March 2021.

“Part of Idaho’s response to my lawsuit was to change the law to allow IDOC to keep more secrets about executions and the sources of lethal injection drugs, and that is a real cause for concern,” Cover said by email. “The lawsuit made clear that there are substantial costs to willful noncompliance with the Public Records Act. The people of Idaho have a strong interest in knowing how the government is carrying out the death penalty in their name.”

Obtaining execution drugs a challenge for Idaho

The records released in the Cover lawsuit pulled back the curtain on how Idaho in 2011 went about relaunching its execution program after 17 years, having last ended a prisoner’s life in 1994.

IDOC soon discovered that lethal injection drugs had over that time become extremely difficult to obtain. Prison officials then contemplated sourcing them from Harris Pharma, an infamous supplier in India, according to the email records from Randy Blades, then-warden of the Idaho Maximum Security Institution, where death row inmates reside. The FDA later seized execution drugs bought by other states and illegally imported into the U.S. from Harris Pharma.

“It was almost impossible to find the necessary drugs that were considered acceptable by the U.S. Supreme Court,” Brent Reinke, IDOC director at the time, previously told the Utah Investigative Journalism Project. “We used every bit of creativity we could because of the importance of what we were charged to carry out.”

The records also show how IDOC actively worked to keep its execution activities off the books. Top-level prison officials spent from confidential cash accounts, directed staff in an internal memo not to make any execution purchases through typical channels, and wound up sourcing the lethal injection drugs from pharmacies with dubious regulatory histories.

“This document is for staff use only. Do not release it to offenders or the general public,” reads the memo, which includes pointers to prison staff on how to avoid the financial detection that could help identify a source of the execution drugs.

Faced with a ticking clock on Rhoades’ Nov. 18, 2011, execution date, IDOC leveraged another state agency to place an order for pentobarbital sodium, a Schedule II controlled substance in the U.S. The supplier that agreed to sell it was the University Compounding Pharmacy in Salt Lake City, records show. State prison officials requested a pharmacist with State Hospital South, a psychiatric treatment center in Blackfoot within the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare network, submit the required U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration order form.

The state’s Department of Health and Welfare lists its mission as being “dedicated to strengthening the health, safety and independence of Idahoans.” An IDHW spokesperson declined to respond to questions from the Statesman about who made the decision to help IDOC obtain execution drugs, nor explained how or why the department got involved.

“The Idaho Department of Health and Welfare requested a clinical pharmacist employee travel to Salt Lake City in November 2011 to pick up pentobarbital from a pharmacy for the state of Idaho,” IDHW spokesperson Niki Forbing-Orr said in an emailed statement. “No one currently working for the department was involved in that decision 10 years ago.”

IDOC paid upward of $10,000 in cash for the lethal injection drugs used in the Rhoades execution, Ross Castleton, a former IDOC deputy chief of prisons, said in a sworn deposition. The drug supplier was later revealed to be the Salt Lake City pharmacy.

Idaho’s decision to buy lethal injection drugs across state lines would be repeated by top brass at IDOC less than a year later.

Idaho next goes to Washington for lethal chemicals

In 2012, IDOC again sought pentobarbital to execute a prisoner — this time Richard Leavitt. He was charged with killing and mutilating a 31-year-old Blackfoot woman, and convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death in 1985.

The day before Leavitt’s death warrant was expected to be issued on May 17, an internal prison report about the execution noted to staff that IDOC had already found another drug supplier.

“IDOC has a good source for the required chemicals this time, and it is anticipated we will not have the same troubles as the last execution,” the May 16 document states. The document does not address what those purported issues were, or if they involved the compounding pharmacy in Salt Lake City. IDOC officials refuse to discuss lethal injection drugs.

Flight records obtained from the Idaho Division of Aeronautics for this investigation show that on May 30, Tewalt and his then-boss, former IDOC prisons chief Kevin Kempf, took a state-chartered flight bound for Tacoma, Washington. They were the only two passengers on the 1-hour, 51-minute trip from Boise to Tacoma Narrows Airport, arriving at 5:16 p.m., and the 1-hour, 31-minute trip back that same night, arriving in Boise at 10:19 p.m. The Division of Aeronautics estimates the round-trip flight cost taxpayers $2,448.

Tewalt, then an IDOC deputy chief of prisons, and Kempf brought with them as much as $15,000 in cash to buy the execution drugs from a Tacoma pharmacist, public records and court depositions from the Cover lawsuit show. Tewalt and Kempf carried the money aboard the flight in a suitcase and made the evening exchange in a Walmart parking lot, Pizzuto’s attorneys alleged in a March 2020 legal filing.

Kempf later submitted an expense reimbursement in fiscal year 2013 for $16,383, which was included in a record released in the Cover lawsuit. A handwritten note in blue next to the line item reads “execution” on the document, which appears to be an internal IDOC financial audit.

Kempf was later promoted to IDOC director in 2014. In a September 2016 sworn affidavit obtained in the Cover lawsuit, Kempf stated that IDOC last possessed pentobarbital in June 2012, for the Leavitt execution.

Kempf left IDOC two years later to become the executive director of the Correctional Leaders Association, a trade group and lobby for the nation’s member prisons. As he exited, then-Gov. Butch Otter, who was in office for the Rhoades and Leavitt executions, pronounced Dec. 16, 2016, Kevin Kempf Day in Idaho, “for his tireless work and dedication to public safety,” according to Kempf’s online professional bio.

Kempf could not be reached for comment through his trade group.

When Kempf left IDOC, Tewalt went with him, working for two years as the association’s director of operations. Tewalt returned to IDOC in December 2018 as its appointed director, while Otter was still governor.

A separate record released in the Cover lawsuit links the 2012 execution drug sale to the Union Avenue Compounding Pharmacy in Tacoma, as well as to a woman who says she knows nothing of lethal injections.

The document — what appears to be a fax dated Jan. 10, 2013 — is on Union Avenue pharmacy letterhead and titled “Receipt of Monies.” It is signed by Kim Burkes, a pharmacist licensed in Washington state who owns the Tacoma compounding pharmacy. A handwritten note paper-clipped to the document also lists contact information for Burkes’ mother, Linda Hathcock.

On the front porch of Hathcock’s home, also in Tacoma, she told a Statesman reporter she had never seen the document before, and didn’t know anything about the sale of execution drugs to Idaho. The only thing Hathcock said she’d done in the past for work at her daughter’s pharmacy was some light cleaning.

The lethal dose of pentobarbital acquired on that May 30 trip to Tacoma was used 13 days later to end Leavitt’s life, Cover lawsuit court depositions and documents reveal.

“The chemical has been purchased,” an internal IDOC report dated May 24 reads. “All necessary chemicals have been obtained,” a follow-up report on May 31 informs staff.

Castleton, the former IDOC deputy chief of prisons, testified in his deposition during the Cover lawsuit that Zmuda, the former IDOC chief of prisons, could also speak to the cost and source of the execution drugs in 2011 and 2012.

Zmuda, now head of the Kansas Department of Corrections, did not respond to Statesman requests for an interview through his office. Kansas also maintains capital punishment and has nine inmates on death row, but it has not executed a prisoner since before 1976.

In December, inside Burkes’ pharmacy — located across the street from Tacoma’s only Walmart — she declined a Statesman reporter’s in-person interview request, and later backed out of a scheduled phone interview. Instead, Burkes texted a brief statement and did not respond to follow-up requests for an interview or emailed questions.

In her written statement, Burkes, 58, confirmed she received an order from IDOC in May 2012, though did not specify which drug she sold to prison officials. She also did not say what she was paid, or how the contact was initiated, or if IDOC officials have been in touch with her since.

“They provided me with the appropriate paperwork and I fulfilled the order and provided documentation of third-party quality control testing,” Burkes wrote. “I released the product to authorized Idaho DOC members … when they came to our pharmacy to retrieve it.”

In February 2017, the Washington Department of Health placed Burkes’ pharmacist’s license on probation for one year for repeat inspection violations in 2015 and 2016, according to records obtained from the health department for this investigation. In addition, she was fined $1,432 and made to write an essay and attend trainings. The violations included stocking expired drugs on the pharmacy’s shelves and possessing insufficient patient information. Burkes’ license was reinstated in 2018 — the same year Washington state abolished the death penalty. It was at least the second time a licensed staffer at Burkes’ pharmacy had been placed on probation.

Washington Department of Health spokesperson Katie Pope said that in the state’s complaint-driven system, disciplinary action is rare. Over the past two years, just 35 of Washington’s 11,000 licensed pharmacists have faced such punishment.

Missing records from Idaho’s controversial 2011-2012 executions

The Idaho Department of Correction is current with its controlled substance license through the Drug Enforcement Administration. Documents released in the Cover lawsuit and also obtained from IDOC for this investigation show the department had such a license from August 2017 to November 2020, and then received a renewal in February 2021 with an expiration date of Nov. 30, 2023.

Ray, IDOC’s spokesperson, said by email that the department was also previously licensed from Nov. 9, 2011, to Nov. 30, 2014, which would have encompassed the Rhoades and Leavitt executions. However, the department has been unable to produce any form of record, including a mandated DEA order form for the purchase of pentobarbital in Tacoma in 2012, like the one State Hospital South submitted to the Salt Lake City pharmacy on IDOC’s behalf in 2011.

IDOC still possessed a copy of that 2011 DEA order form when it fulfilled the court order to turn over all records to Cover last year. A 2012 order form that the DEA would have also required of IDOC cannot be found, including in a follow-up public records request as part of this investigation, Ray said.

“IDOC was in full compliance with all DEA regulations for the 2011 and 2012 executions,” Ray said by email, directing a Statesman reporter to the DEA. “It would be inaccurate to suggest that IDOC was not in compliance with federal regulations because the department cannot produce records that expired long ago.”

A DEA regional spokesperson declined to confirm or answer questions about whether IDOC was properly licensed to handle Schedule II controlled substances in 2011 and 2012. The federal agency requires that registered agencies keep records involving all controlled substances for at least two years.

Burkes, the Tacoma pharmacist, did not specify in her written statement what documents IDOC provided to her when it bought the drugs used in Leavitt’s execution. She said her pharmacy generally keeps records longer than is required, but not more than five years.

Washington state also requires pharmacists to report all controlled substance dispensations to the state’s online prescription monitoring program. The obligation predates Burkes’ sale to IDOC in 2012, but the database is confidential, and review of the information is restricted to providers, prescribers, and state regulatory agencies, as well as law enforcement and prosecutors.

Ray acknowledged IDOC did not have a DEA license from December 2014 through when the department applied for a new controlled substance certificate in March 2017, which the DEA issued to IDOC in August 2017. The department allowed the certificate to lapse because there were no imminent executions during that time frame necessitating the license, he said.

Following Leavitt’s execution on June 12, 2012 — a Tuesday — IDOC in an after-action report, a document created to improve procedures for future lethal injections, recommended choosing a different day of the week for putting prisoners to death. “Wednesday is a better execution day, rather than Tuesday, because of the quick turnaround at the beginning of the week,” the report reads.

On May 6, 2021, an Idaho district court judge signed the death warrant of inmate Gerald Pizzuto. His execution was scheduled for June 2 — a Wednesday — before he was granted a clemency hearing in November, which postponed his scheduled lethal injection.

During the hearing, the Idaho Attorney General’s Office presented the state’s case for maintaining Pizzuto’s death sentence, and the parole board deliberated for another day behind closed doors before issuing its ruling a month later on Dec. 30. The seven-member board voted 4-3 to recommend that Pizzuto be pulled from death row and allowed to die in prison of natural causes.

Gov. Brad Little had 30 days to consider the recommendation and approve or deny it. However, he rejected it on the same day, which stands to restart Pizzuto’s execution window.

Pizzuto still has several active appeals in state and federal district courts. His attorneys also are challenging in court Little’s power to overturn the parole board’s ruling in clemency hearings, citing conflicting language between state law and the Idaho Constitution. A hearing is scheduled in state district court in Idaho County on Thursday.

The AG’s Office and IDOC declined to comment on the governor’s clemency decision, and prison officials have gone silent as prospects grow for reissuance of Pizzuto’s death warrant.

Eppink, the ACLU of Idaho’s legal director, said it remains telling that the state’s prison system staged such a costly, multiyear legal battle over the release of records that Idaho’s highest court recognized were owed to the public. When it comes to putting people to death, he said, transparency about the process is essential to democracy.

“What governments, including Idaho, have tried to do is to write the people out of that whole equation, by not telling them anything and shrouding this whole process in secrecy,” Eppink said. “And when it comes to lethal injection drugs, that is the mechanism of death.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies