Panthers RB Chuba Hubbard knows when to make noise — on or off the field

Lean in. A little closer.

OK, you’re ready.

Chuba Hubbard has something he’d like to say.

When he speaks, his tone is even. Every word is deliberate. A quiet person who likes to keep to himself, attention is not something Hubbard seeks or particularly enjoys.

When he sees something that he thinks is wrong, however, he has no problem being forthright. He got that from his mother, Candace.

“I’m somebody that believes in doing the right thing,” Hubbard said. “The thing is, I can be a vocal person, I can speak up when need be, and that’s just what I do.”

Last year that was put in the international spotlight when he spoke out against Oklahoma State head Mike Gundy for wearing an OAN T-shirt, symbolizing support for a far right-wing cable news network.

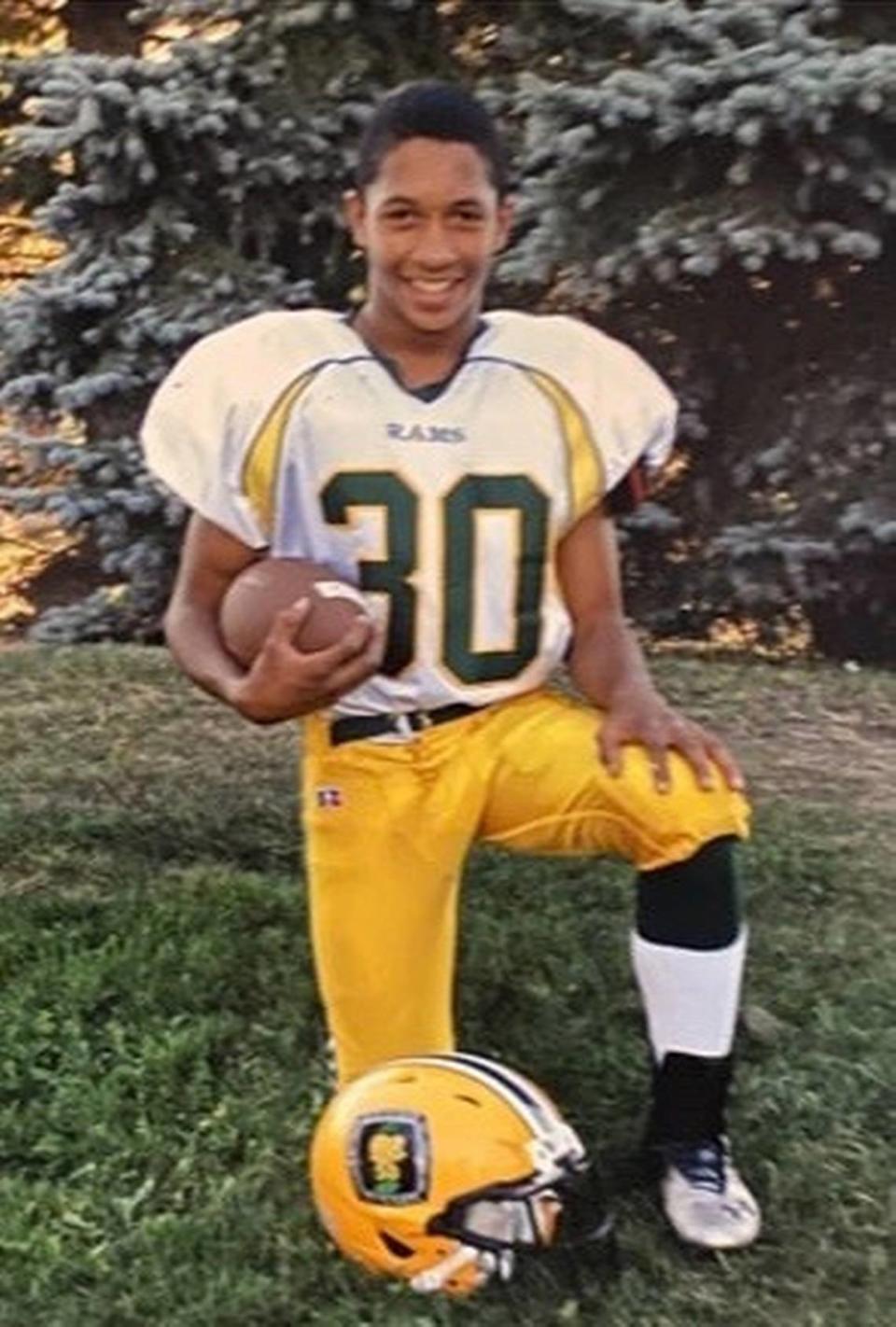

Throughout Hubbard’s life, his speed and athletic abilities have brought him attention.

On the football field, Hubbard couldn’t be louder. Ask any coach who has game-planned against him, even Matt Rhule.

That talent has brought the running back from Edmonton, Canada, to the Carolina Panthers in the most unlikely of fashions, and his choices off the field have made him a hero to many back home.

What’s a Chuba?

What motivates Chuba?

There’s a long pause before Candace Hubbard answers.

“He always says me,” she responds emotionally.

Chuba Robert-Shamar Hubbard’s name is Nigerian. The youngest of four, he was raised by Candace, a licensed nurse, and later his stepfather, Lester Yearwood.

Candace, who originally hails from Manitoba, a Canadian province east of Alberta, describes Chuba’s entire life as a hurdle. Chuba was born in Edmonton and the family moved around the area when he was young. Money could be tight.

“His mom has been unbelievable,” Tanner Stephens, one of Hubbard’s high school coaches, said. “ … She’s there to help him get through anything he needs. They have a really awesome bond.”

From a young age, Chuba often chose to stay in his room when he wasn’t playing a sport, despite having his older siblings in the house. Once he becomes comfortable around someone, however, Hubbard’s humor shines. He is quick to make fun of himself. Hubbard often points out his surprise that people even know “what a Chuba is.”

Candace is a self-described strict mom, but Chuba often confides in her. As he has grown, she continues to see more of herself in him, including that need to use his voice.

“I’m a very outspoken person. If I see something that isn’t right, I’ve always said it just the way it is,” Candace said. “He’s always been like that. If something’s not right, he’ll speak up about it. Though he’s very quiet, if it’s not right ... he wouldn’t hold back.”

A head start

That bond extends to having a partly shared athletic background. Candace was a sprinter, although she’s still trying to track down the records to prove it to her son. Chuba’s records, on the other hand, aren’t so hard to find.

When Hubbard was in first grade, he befriended Simon Timmer and was quickly welcomed in by his family, which included eight children and his mom, Corrine, who is a track coach.

“Anyone who befriends my kids ends up being part of the track team,” Corrine Timmer said.

Hubbard is competitive — you don’t rush for more than 2,000 yards in a college season without that drive. It’s another of those shared family traits.

If Chuba didn’t win, he felt like he was letting his coaches down. In 2009, he competed at the Hershey’s Track and Field Games in Hershey, Pa., and took bronze in the 100-meter race.

He returned to Hershey two years later at 12-years old and won a gold medal for long jumping, a skill that Timmer points to as helping his football career, and two years after that, he went back and won the 100-meter dash in 11.62 seconds.

With dreams of one day competing in the Olympics for Canada, Hubbard finished fifth at the 2015 Cali IAAF Youth World Championships, making him one of the best in the world at his age.

At the same time, his football career was skyrocketing.

Uncatchable

Byron Benson, a youth football coach, can recall his kids mentioning how fast Hubbard was out in the neighborhood, playing hide and seek. Hubbard was 9 years old and his family had recently settled in Sherwood Park, located just outside of Edmonton, with a population around 75,000.

OK, well it’s normal for some kids to run track, Benson first thought. No big deal.

“No, no,” his kids said. This is someone who recently competed in Hershey, bringing back chocolate to share as evidence.

Then Benson saw it with his own eyes when Hubbard invited the family out to one of his track meets.

“This race, he was so far out in front of it that he’s coming around the bend and looked up in the stands and waves at us. Not in an arrogant way. He’s just so happy to see us,” Benson said.

Hubbard had interest in adding football to his resume from being around other kids who play, like Benson’s son, Nolan, and watching CFL and NFL games on TV. And though Candace was worried about her son playing tackle football, “you gotta be fast enough to be able to contact him,” Benson said.

He helped get Hubbard connected with his atom team (ages 8-10). The season had already started, so there wasn’t as much time to teach him the intricacies of football, so they started him out with something simple: kick returns.

On the first play, the ball was kicked over his head. He ran back to the goal line to pick up the ball — the exact location of the ball may have been embellished with the story being retold over the years — and just took off. It was the first of many touchdowns to come.

“When he was 9 years old— I can see him saying to me — ‘Mom, I’m going to go to the NFL,’ ” Candace said. “And he was serious.”

Hundreds of potatoes

There was no shortage of ways to quantify Hubbard’s success on the football field.

His coach for two years at the bantam level, Jim Skitsko, grew potatoes on his farm. As he began his second season coaching Hubbard, Skitsko offered his budding running back a bag of potatoes for every touchdown he scored. After about five games, Hubbard had brought home 20 bags.

“He comes over to me after practice one day and says, ‘Coach, if it’s OK with you, my mom says she has enough potatoes,’ ” Skitsko said.

While Sherwood Park has a successful football program, players like him don’t come around every year in Edmonton.

There’s the game where he had seven carries and six touchdowns. The 300-yard games. The 15-yards-per-carry average.

And as his skills developed on the field, so did his voice. He stood up for teammates to his coaches when he felt like he needed to, although Candace said, as a teenager, he may not have always 100% of the time been on the right side — a learning experience of its own.

A friend and fellow football player passed away from an overdose while he was in high school, a tragic event that strongly impacted Hubbard. He spoke out for his friend and in support of helping others.

Despite his growing reputation, he was still a Canadian trying to get noticed by NCAA football programs, no easy feat. Without someone helping him like he was helping others, who knows where he would be.

Jed Roberts, a 13-year veteran in the CFL for the Edmonton Eskimos, had heard about Hubbard’s talents and saw him working out at a local combine training facility. He asked Hubbard if he would mind if he passed along his information to a former teammate, Marty English, who was then coaching at Colorado State.

A phone call from then-Colorado State head Mike Bobo shortly followed while Hubbard was sitting in physics class.

His eventual path to Oklahoma State was also made possible with some help. Amen Ogbongbemiga shares a Nigerian background with Hubbard and competed against him through high school in Alberta.

The linebacker got to Oklahoma State a year prior and brought Hubbard to the staff’s attention. Former Oklahoma state running backs coach and current UNLV head coach Marcus Arroyo soon after made the Cowboys the first Power-5 school to offer Hubbard.

Once in Oklahoma, his football career didn’t get off to the best start. It was “the most humbling experience of my life,” Hubbard said.

Last on the depth chart, Hubbard redshirted his freshman year.

The adjustment to the rules of American football, trying to catch up in weightlifting, something that Canadian high school players don’t do as much, plus the significant distance from his family and mom for the first time took a toll.

“He had a lot to learn and just from Canadian football to American football was a whole different world for him,” Oklahoma State running backs coach John Wozniak said. “Having to learn how to pass protect and some of the nuances of the game. He was really raw when he got here.”

Ogbongbemiga, now with the Los Angeles Chargers, became a part of his close group of friends. The toll of transitioning to a new country and re-learning a game Hubbard had played for about a decade was evident to those close to him.

“It seemed like he really didn’t know how to play football again, that’s what he would say,” Ogbongbemiga said. “He kind of was getting frustrated with himself, because he came off some phenomenal high school seasons, but he stuck to the process and just trusted everything.”

What followed was 740 net rushing yards as a sophomore and then 2,094 his junior season, setting marks that only sit behind fellow Cowboy Barry Sanders’ 2,628-yard Heisman-winning season in 1988.

Even with his stats, Hubbard wouldn’t become a national name until the next summer, 2020. Amidst a difficult year that involved him testing positive for COVID-19, and social justice movements sweeping the country after the police murder of George Floyd, Hubbard called out his head coach on social media for the OAN shirt.

“I will not stand for this,” Hubbard tweeted. “This is completely insensitive to everything going on in society, and it’s unacceptable. I will not be doing anything with Oklahoma State until things CHANGE.”

I will not stand for this.. This is completely insensitive to everything going on in society, and it’s unacceptable. I will not be doing anything with Oklahoma State until things CHANGE. https://t.co/psxPn4Khoq

— Chuba Hubbard (@Hubbard_RMN) June 15, 2020

A public apology of sorts from Gundy followed, and a call for change.

“[I was] made aware of some things that players feel like can make our organization, our culture even better than it is here at Oklahoma State,” Gundy said in a video after the incident. “I’m looking forward to making some changes, and it starts at the top with me.”

Hubbard’s goal was to help make the experience better for Black students at the school. He later said that some things had improved since he spoke up.

Peace be with you all pic.twitter.com/u5leqHVfao

— Chuba Hubbard (@Hubbard_RMN) July 21, 2020

“Chuba would never say something that isn’t to what he was feeling,” Candace said. “We talked about it and we could have approached it differently, but he still stood for what he believes is right. … I’m so proud of him for standing up for all his teammates.”

A big impression

In the 2019 season, Hubbard ran for a cool 171 yards and two touchdowns against Rhule’s Baylor Bears. Baylor won the game, 45-27, but Rhule made sure to note the effort of the opposing team’s back.

“I just have to say this: I thought Hubbard was amazing,” Rhule said. after the game. “You don’t ever know how good someone is until you play them, and we just couldn’t tackle him a lot of times.”

A high ankle sprain and groin injury hampered his senior year and likely hurt his draft stock. He could have come out a season earlier and may have been picked earlier than the fourth round, but getting his diploma was a goal. Hubbard never missed a day of school growing up. For anything.

The sound of fellow graduates cheering him on as he walked across the stage in Stillwater, Okla., to get his diploma a month ago meant so much to the Hubbard family, watching virtually, a country away, especially after some of the backlash he received for speaking out against his coach.

“A big thing about me going to the States was obviously going to play football at a high level, but also going to mature as a young man and to get my education,” Hubbard said. “I wanted to make sure that I did that when I left.

“ … I also wanted to show the kids that are gonna come after me, after everybody else, that school’s important. Football and all this stuff can take you a far way but education, and having that knowledge, is a different type of strength.”

As he enters his professional life, playing for the coach Hubbard caught the attention of just a couple years prior, he again is not at the top of the depth chart, playing behind Christian McCaffrey. A potentially humbling experience not so different from what he experienced in college.

Starter or backup, Hubbard just being in Charlotte helps to continue to pave a path for athletic kids like him back home. He made history as the first running back drafted from Canada since Tim Biakabutuka was selected by the Panthers in 1996.

“We felt Chuba’s one of those guys that can develop into a quality number one running back in the NFL,” current Panthers running back coach and former Baylor coordinator Jeff Nixon said.

Listen

Today in Sherwood Park, young football players swap tales of what Hubbard accomplished.

So many want to grow up to be just like him.

It’s a place that’s birthed 10 NHL players, seen 17 drafted and sent countless prospects through the junior hockey ranks. But football players in the NFL? Just one.

Hubbard can be referred to by just “Chuba” in Edmonton. Everyone will know who you are referring to. In pockets of the United States, that same truth exists.

Before leaving college, Hubbard started a charity, Your Life, Your Choice. It’s his goal not to make an impact in one specific area, but to help people around the world in a variety of ways, such as getting an education, finding a job and rehabilitation.

Regardless of whether he likes it, even more people will soon learn his name. Hopefully, when he speaks, they’ll be listening.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies