What Canadians need to know about how climate change is affecting their health

Our planet is changing. So is our journalism. This story is part of a CBC News initiative entitled "Our Changing Planet" to show and explain the effects of climate change and what is being done about it.

Climate change is hurting us, and a global report released today warns the impact on people's health — especially the elderly, the young, and the vulnerable — will get far worse if leaders fail to commit to more ambitious targets at COP26, the upcoming United Nations conference on climate.

The world is already 1.2 C warmer than it was between 1850 and 1900, the pre-industrial period, and the latest report by the Lancet medical journal measures how that change is affecting people's health around the world.

The authors found the health impacts of climate change are getting worse across every factor measured, including the physical and mental toll of extreme heat, the spread of infectious diseases, and decreasing crop yields and food insecurity. A total of 93 authors, including climate scientists, economists, public health experts and political scientists, contributed to the analysis.

"When people are ... thinking about climate change off there in a far away, distant land, in a far distant future, these reports shatter that myth," said Ian Mauro, the executive director of the Prairie Climate Centre at the University of Winnipeg. Mauro was not involved in the Lancet report.

"They show that it is happening now, that it is real, and that the consequences at this relatively early stage in the climate game are tragic now. Just imagine decades into the future."

It's a reality more Canadians have experienced this year — from drought to wildfire to deadly heat waves. But the Lancet authors also call out Canada as a country that has a gap between its carbon-cutting ambitions and its strategy to make it happen.

Canada's emissions growing

While the Lancet report's authors credit Canada's government with taking positive steps through carbon pricing and mandating new vehicles to be zero-emission by 2035, they warn more is needed.

"At the average pace of decarbonization observed between 2015 and 2019, it would take Canada over 188 more years to fully decarbonize its energy system," stated a policy brief provided by the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change

"Canada and the U.S. are the only G7 countries that have increased emissions since signing the Paris Agreement — and Canada's have grown the fastest, primarily due to oil and gas production."

The report, entitled a "Code Red for a Healthy Future," highlights this time as a fork in the road, a point at which leaders can either choose to lock the world into increased emissions and catastrophic global warming, or to focus on meeting the goals set out in the Paris Agreement.

"Despite the gory headlines of doom and disaster, the best available science is still saying there's a pathway for us to achieve some level of human resilience that will create a healthy future for our kids and grandkids," Mauro said.

WATCH | Developed countries still short on pledge to help poorer nations act on climate:

Deadly heat wave

One prime example of the consequences of human-caused climate change is the deadly June 2021 heatwave, which is mentioned high up in the report.

When record-breaking temperatures soared above 40 C in B.C. and the Pacific Northwest of the U.S., hundreds of people died prematurely from the heat.

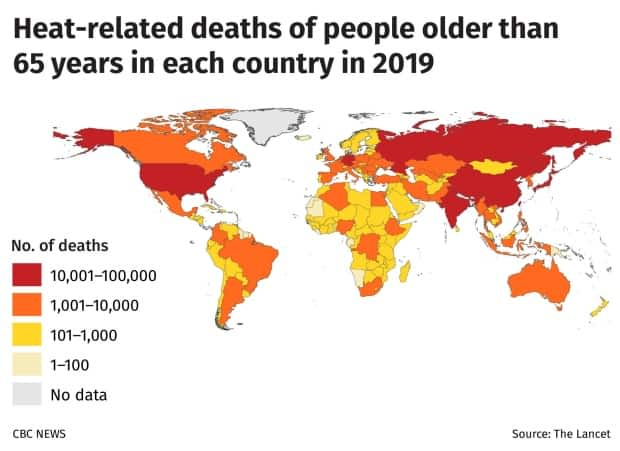

Exposure to extreme heat increases the risk of death from cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory conditions. According to the Lancet report, those most at risk are society's most vulnerable — people facing social disadvantages, children less than 1 year old and seniors older than 65 years.

A global team of climate experts reported this summer the heat dome would have been "virtually impossible" without human-caused climate change, and extreme heat events will become more likely and severe as the plant warms.

"What we can safely say is that the heat wave was made much worse by the amount of climate change that we have experienced in the last century and a half," said University of Victoria climatologist Faron Anslow, who is an author of the study which was cited by the Lancet report.

Rising temperatures are also having an impact on people's mental health and their ability to work, according to the Lancet. In 2020, heat cost Canadians a loss of almost 22 million hours of labour, which is up 151 per cent compared to the 1990-1994 average.

Wildfires disproportionately impact Indigenous people

The report also points to how wildfires are increasingly a threat to Canadians.

According to the authors, Canada experienced an 18 per cent increase in annual daily population exposure to wildfires from 2001-04 to 2017-20.

That was before the village of Lytton, B.C., which had recorded the hottest temperatures ever in Canada, burned to the ground last summer — devastating many homes and buildings of the Lytton First Nation.

In northwestern Ontario too, summer wildfires raised concerns about air quality and forced First Nations communities to evacuate.

"Overall, Indigenous Peoples, including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit, are disproportionately impacted by fire, with a 33 times higher chance of evacuation due to wildfires for First Nations persons living on reserve compared to those living off-reserve," states a Canada-specific policy brief stemming from the Lancet report.

Smaller crop yields are hurting farmers

Canadian farmers are also feeling the impact of climate change, especially in the Canadian prairies, where drought made for an especially bad 2021.

"Some of them were half of a crop, a third of a crop, and in some of the places, the crop wasn't even harvested because it was so poor and thin," said Darrin Qualman, the director of climate crisis policy and action at the National Farmer's Union.

Qualman, who lives near Dundurn, Sask., said in recent years they've had dry winters in the province, but were saved by rains in June and July.

This year that rain never came.

According to the Lancet report, in every month of 2020, up to 19 per cent of the global land surface was affected by extreme drought. From 1950 to 1999, that number never rose above 13 per cent.

The authors warn drought and warm temperatures are reducing the yields of staple crops around the world, which could contribute to food insecurity.

Some crops in Canada also saw lower than average yields in 2020, according to the report. Nationally, the total duration of crop growth was down 9.7 per cent nationally for soybeans, and down 3.4 per cent for spring-wheat, compared to 1981 to 2010.

While losses in the Canadian prairies aren't at the point where grocery stores will have empty shelves, Qualman said they are seeing real impacts on farmers and their communities.

"I think the hardest hit are the cattle farmers who maybe didn't get the hay crop they need for the winter, and didn't have much grass to graze on in the summer," he said.

But whatever this year's losses mean for farmers, Qualman said farmers will suffer greatly down the road if nothing changes.

"Maybe more than any group in Canada, rural people in the Canadian prairies really need to be concerned about climate change because it's our farmland area that's going to be the hardest hit, and the first hit, and the most directly hit if we don't get off the course we're on now," he said.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies