A bust of the lone Black adventurer in the Lewis and Clark expedition mysteriously appeared in an Oregon park. Who was York?

When the early-1800s expedition to the Pacific Ocean led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark returned after two years and 8,000 miles, members who traveled with the now-famous pair of explorers received titles, accolades, land and fame.

Except for the Black man who had no say in whether he was coming along.

York, an enslaved man owned by Clark and the first Black man to reach the Pacific, wanted his freedom. Or, at the very least, York wanted to be allowed to live with his wife in Louisville, Kentucky.

Clark refused both requests. When York became despondent, Clark saw fit to punish York with a “trouncing,” historians said. While he did eventually gain his freedom, accounts of York's life after the expedition vary, and his story has been mostly ignored or misconstrued.

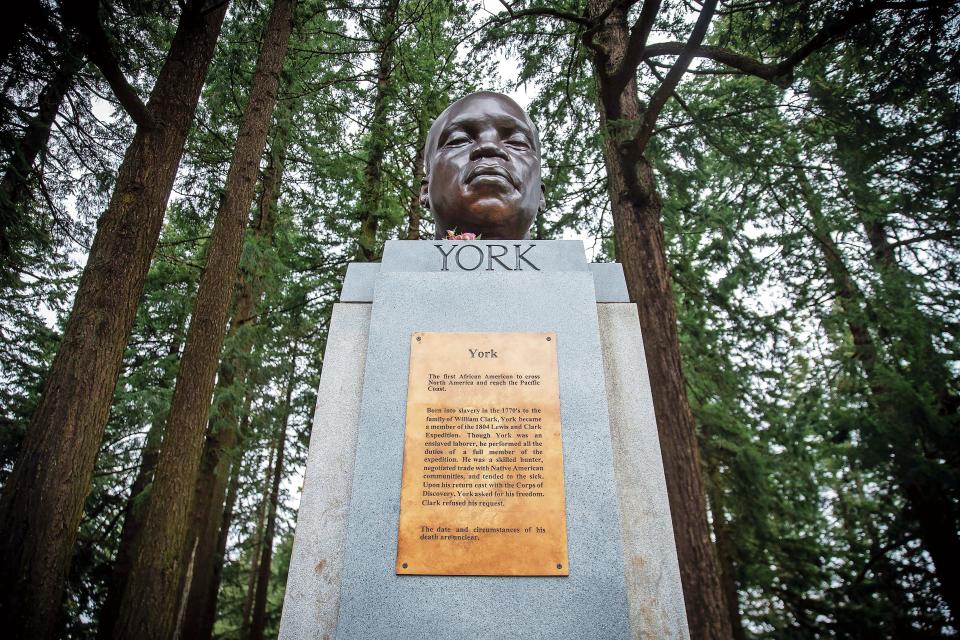

In Oregon, an unknown artist gave York the recognition that experts say his contributions to the Corps of Discovery deserved. A bust of York, mysteriously placed in Portland’s Mount Tabor Park in late February, depicts a bald man gazing solemnly downward and includes a plaque describing the significant role of the expedition's lone Black adventurer.

It’s a gesture experts who spoke with USA TODAY hope will spark new interest in York.

Darrell Millner, a professor emeritus of Black studies at Portland State University, said York made “serious and important contributions to the success of the expedition.” He added York was the only enslaved man who took part in the full expedition.

Nearly 100 Confederate statues were removed in 2020: Hundreds remain, new SPLC data shows

“It was not a situation in which (Clark) was bringing some kind of luxury along,” Millner said. “York was selected because he met all the criteria for the kind of individual they were looking for to be a part of their party to make it a successful expedition.”

The “impressive” bust was a “complete surprise,” Portland Parks & Recreation Director Adena Long said in a statement to USA TODAY. She offered thanks to the artist or artists for bringing "this important story to light for many Portlanders and people across the country.”

“The bureau has a memorial policy that says if a tribute is placed in a park and isn’t a danger to the public, PP&R will let it temporarily remain in place. Parks staff have inspected the installment, and it is safe, so this memorial to York will remain in Mt Tabor Park for the time being,” she said.

Who was York?

Little is known about York, aside from what can be gleaned from Clark’s journal entries and correspondence to family.

Experts told USA TODAY that York was born around the same time as Clark. His father, known as “Old York,” and mother were owned by Clark’s father. He grew up alongside Clark and had many of the skills needed for a journey into what was then unknown territory.

“(Clark) just automatically included York and knew that York could do everything that would be needed and expected on the expedition,” James Holmberg, curator of the Filson Historical Society in Louisville. “He could hunt, handle horses, handle boats, he could swim – according to a journal entry – he was able to do all these things. He made camp life easier.”

Clark called York “fat” in one journal entry. Holmberg disputed that take.

Do Lincoln, Washington deserve statues? Chicago flags 41 controversial monuments for scrutiny

“You can’t do what they did day-in and day-out and truly be fat,” he said. “He was probably just a big guy.”

Other journal entries include the surprise Native Americans, who at the time had never before seen a Black person, felt after Clark ordered York to dance for them (“that So large a man Should be active,” according to Clark). Another tale from Clark includes York telling Native Americans he was “wild & lived upon people” before Clark found out.

Native Americans were fascinated with, and in some cases awed by, York, experts said. Some tribes believed he was powerful and could transfer that power through sex with women, Holmberg said.

York was given a vote when explorers were discussing what route they should take, according to a journal entry. At one point, he searched for Clark and other explorers during heavy storm, "greatly agitated, for our wellfar," as Clark wrote. When Clark was sick, York swam to a "Sand bar" to gather greens for dinner.

Millner said there are a few statues of York around the county, though the reality is we don’t know what York actually looked like, aside from a few “sketchy descriptions of him that come from the journals of Lewis and Clark.”

“A slave in the early 1800s was not going to be the focus of a lot of attention in terms of how his story would be preserved in American culture,” he said. “They didn’t go around painting pictures of the slave population. They didn’t go around describing their lives in glorious detail.”

What happened to York?

After the expedition, with Clark preparing to move to St. Louis in 1808, York asked to be allowed to stay in Louisville to be near his wife, Holmberg said. The Filson curator added York offered to be hired out in Louisville, but then asked for his freedom. Clark said no.

“Clark admits in one of his letters that he whips him,” Holmberg said. “He says he gives York a ‘severe trouncing’ and he’s behaved himself since then.”

Clark eventually sent a still-enslaved York back to Louisville, telling his family to hire him out to a “severe master,” Holmberg said. That was meant to break York's spirit, Millner added.

By 1814, Clark doesn’t know what’s become of York. The “last definitive documentary reporting we have of York” comes in 1815, when Clark’s nephew reports York is a driver for a freight-hauling business, Holmberg said.

Speculation suggests York was freed sometime after this – Millner said York remained a slave “probably for as much as 10 years” after the 30-odd members of the expedition returned.

Katrina Jagodinsky, Susan J. Rosowski associate professor of history at University of Nebraska in Lincoln, which hosts the journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition online, said Clark spoke of York “in disparaging ways.”

Clark suggested York was not equipped for freedom is an “indication of Clark’s sort of lingering racism – something he held for the remainder of his life,” Jagodinsky said.

Harriet Tubman: What to know about the abolitionist hero and the effort to get her on the $20 bill

York’s fate isn’t clear. Holmberg said York was freed and set up by Clark with some horses and a cart for a freight-hauling business, but eventually was cheated and tried to make his way back to Clark.

Holmberg and Millner said York died of cholera before he could reach Clark. Another theory is York eventually made his way to a group of Native Americans, becoming a chief and warrior.

Millner and Holmberg disagreed.

“I think Clark knew exactly what had happened to York,” Holmberg said. “He was informed about his sad fate. His fate was to lie in an unmarked pauper’s grave.”

What's the true story of York?

The story of York has changed over the years, with different generations defining his role in different ways.

Millner described three versions of York’s tale.

The first is the enslaved man who was ignored and cut out of the conversation entirely. The second is a caricature, a “happy” slave stereotype made to discredit York’s contributions. The third is the tale of York as a “superhero,” introduced around the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, when Black people needed role models to look up to.

None of the three are accurate, he said. The “superhero” version, where York apparently knew French and “guided” Lewis and Clark is just as inaccurate as the caricature.

York’s story is “remarkable enough in its own right,” Millner said.

Dig deeper on race and identity: Subscribe to This Is America, USA TODAY's newsletter

“York has essentially been… a figure who has reflected the racial needs of every generation in American society, from the actual expedition to whatever generation you might currently be in,” Millner said.

York was initially left out of the conversation due to the inherent contradictions of American society at the time. It’s a fundamental contradiction for a representative democracy to have slavery, Millner said, so slave owners and to describe slaves in ways that made it seem like slavery was the “natural condition” for Black people, one to the advantage of both the slave and the master.

Black people were described as lazy and incapable of operating independent of masters, Millner said.

“He had to disappear from the story, or those contradictions between the way Black people actually were and the way they were described would become available and apparent and would have to be explained,” he said.

Coming to terms with York means grappling with a complex period of American history, Jagodinsky said.

“The more you know about York, the more difficult it is to hold William Clark as an uncomplicated hero,” she said. “It may be that some readers like to think of William Clark as a champion of democracy and liberty because of his participation in the expansion of American territory and, therefore, values.”

She added, “When you follow his treatment of York, it’s difficult to uphold that.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Who was York? Bust of Black explorer mysteriously appears in Oregon.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies