Blake Morrison: Memoirists like me are accused of being mercenary and opportunistic

If you’re reading this, my sister is dead. I may be dead too, but that’s beside the point, for you if not for me. Many years ago I resolved not to write about her while she was alive, or rather not to publish anything that I had written. She – Gill – had walk-on parts, like a film extra, in two memoirs I published about our parents: And When Did You Last See Your Father? in 1993, and Things My Mother Never Told Me in 2002. That’s all it was: the odd look-in or passing mention. There was plenty to be said but not yet. Even if she had given me carte blanche, the page would have stayed blank. You can’t write an honest memoir when the subject is alive. At any rate I can’t. Death is the only permission.

After those books about Mum and Dad came out, I was sometimes asked if I had another memoir in me. No, I’d reply, I write fiction these days because I’ve run out of family. Once or twice I answered even more facetiously: I don’t know if I’ve another memoir in me but my sister’s quaking in her boots. There’s an assumption that to write honestly about someone is an act of aggression; that’s the gallery I was playing to. But I felt no aggression towards Gill – didn’t then and don’t now. She’s gone, that’s all, and though there’s no retrieving her I’d like to make sense of who she was and what she became. It wasn’t just that she changed over time. She could change from day to day. Drink made it worse but the origins went deeper. You never knew which you’d get, the kind and loving Gill or her doppelganger. Two sisters.

I had another sister as well. Josie’s a smaller part of the story I’m telling. A half-sister, whereas Gill was full (and often full-on). A baby sister whose relation to us was never acknowledged. A sister I didn’t know was my sister until eight months before she died.

Two sisters, both younger than I am and both dead. It’s painful to think about that and tempting to let them be. But I want to understand why their lives took the direction they did – and why they died, self-destructively, before their time. When you grow up with a lie, as my sisters did, it’s important to be truthful. Soft-pedalling would be cowardly. And the truth isn’t malicious. I’m here to commemorate them, not expose.

It may be that I’ve another more selfish purpose: self-exoneration. When you’re newly bereaved, and the death of the person you’re mourning strikes you as preventable, guilt is impossible to avoid. Why didn’t you meet more, speak more, tell them you loved them (assuming you did)? If you had, might you have saved them? My sisters’ deaths left me feeling neglectful. And when I turned to books for comfort or commonality, I found neglect there too. I hadn’t expected the choice to be so limited. Why did so few books explore brother–sister relationships?

Some of the brothers I came across were cruel to their sisters, others gentle and protective. Either way, I couldn’t help measuring myself against them. I’ve never pined for a brother; the books in which brothers feature, whether novels or biographies, reminded me why. Still, I was grateful for my immersion in sib-lit. Even at its gloomiest, it helped me get my bearings.

That said, the authors I read were helpful only up to a point. They hadn’t written about my sister – or sisters. Only I could do that. I had letters and diaries to draw on; relatives whose memories I could check against mine; photos to remind me of episodes I’d half forgotten. And where there were gaps or obstructions, I was forced to surmise. I didn’t write a biography but it’s closer to biography than it is to fiction. It’s life writing. And as with most life writing, the trigger for it was death.

There’s a name for children born close together: Irish twins. Gill and I weren’t quite that but Mum was Irish and two of her siblings had been born just 11 months apart. George Eliot has a sonnet sequence, Brother and Sister, which celebrates this kind of early childhood proximity where “the one so near the other is”. Any gaps are minor, “a Like unlike”, “the self-same world enlarged for each / By loving difference of girl and boy”. The closeness can’t last for ever but “the twin habit of that early time” outweighs the pain of later separation. A like unlike says it well: Gill and I were of a piece but different; in the self-same world but worlds apart.

Nabokov said of his brother Sergei: “We seldom played together, he was indifferent to most of the things I was fond of.” Did Gill and I play together? We must have. Yet I can’t recall it. While I raced my Dinky cars, Gill was giving tea parties to her dolls, each of us on our own planet, the separate universe of Girl and Boy. Did she mind? Did I? Not really. Decades before I became one, I sometimes thought of myself as an only child.

She was a bonny baby, everyone said, cherubic almost – pink cheeked and with lovely blond curls. She also cried a lot as a toddler. No big deal, Mum and Dad said, she’ll soon grow out of it – tantrums were just the flip side of laughter. As the Longfellow rhyme said: “There was a little girl, / Who had a little curl, / Right in the middle of her forehead. / When she was good, / She was very good indeed, / But when she was bad she was horrid.”

Gill wasn’t horrid, only distressed. When asked what the matter was, she couldn’t account for it. She had tears but no words. And that made her difficult to console.

Nabokov, in Speak, Memory, on the parenting he and his brother Sergei had, said: “I was the coddled one; he the witness of coddling.” Did Gill feel uncoddled? Or that she somehow mattered less, because she was a girl?

Like me, Gill must have seen that Mum, for a time during our childhood, was unhappy. But how could she help when she didn’t know the reason? Even if she had known that Dad was having an affair with a family friend we’d been encouraged to call Aunty Beaty, that he had fathered her child, she wouldn’t have understood. Had she been older, she and Mum might have comforted each other. Both were feeling a sense of abandonment: the man they loved most in the world had turned his attention to another woman and another girl. He still behaved as if he loved them. But not with the passion they were used to. Not with the exclusivity that helped them feel good about themselves.

“Never put it in writing,” Dad liked to say. Before he married, wooing Mum while a doctor in the RAF, he did put it in writing: what he felt about her; what he thought about life, sex, religion, politics, medicine; how he hoped they would marry when the war was over. But with Beaty he was circumspect. There were no love letters that their spouses could intercept. Or none that survived. It was the same with Josie. Nowhere did he acknowledge her as his child. No words betrayed the secret. Only – eventually – his DNA.

The early years in any life are formative, some would say all-defining: the child is mother to the woman. But was Gill’s childhood especially painful? Not in her view. Were she around, she’d tick me off for suggesting as much. “I’ve good memories of childhood. If it had been bad, I wouldn’t have had two children of my own.” There were things that might have damaged her: the teasing at school, the slow poison of patriarchy. And the combination of an enigmatic mother, overbearing father and self-absorbed brother might not have been ideal. But I mustn’t let the bad stuff overwhelm the good or project my present sadness on to the past. I’ve been looking for moments – and more than moments – when things went wrong for Gill. But she would deny they did go wrong. “If you’re searching for reasons why I turned to drink, you’re barking up the wrong tree.”

Despite her drinking, Gill became a good mum herself. She didn’t work after marrying her husband, Wynn, and spent hours helping her children Louise and Liam to read and do sums. Later, when they started at the village school (the one Gill and I had gone to), she spent the day cooking and baking for them, even when her failing vision, due to a combination of eye conditions, made it difficult.

But over time, she became very low. Along with a fear that Wynn no longer loved her, there were several factors behind her depression, among them an inferiority complex, her eyesight problems and the trauma of a car accident that left Louise, as a baby, in intensive care. But in the end, it came down to one thing: booze. No getting round it. Her drinking was out of control.

I don’t want to rob her of her dignity. But when she was pissed she had no dignity. And I’m on a mission here – not just to be honest about her addiction and its impact on the people close to her, but to demythologise the romance of heavy drinking.

Gill drank to excess from distress ... we pitied her and we blamed her, both at the same time

Literature – American literature especially – is rich in examples of alcoholic excess, mostly glamorised. Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Hart Crane, Tennessee Williams, Dorothy Parker (“I’d rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy”), Ring Lardner, Raymond Chandler, O Henry, Jack London, Delmore Schwartz, F Scott Fitzgerald (“Too much champagne is just right”), John Berryman, Jack Kerouac, Charles Bukowski, Anne Sexton, Patricia Highsmith. There are embarrassing episodes, but little mention of the fallout from constant heavy drinking: illness, injury, insomnia, squalor, violence, misery for oneself and others.

Gill drank to excess from distress. It wasn’t just losing Dad, who died of cancer in 1991, but in the years that followed, losing the mother she knew. Though free of dementia, Mum had spells of confusion. Occasionally she’d wander down the drive and into the road, as if looking for someone or something – just as Gill did too, when drunk, though never (as far as I know) at the same time.

Mum’s decline was hastened by the strain of seeing Gill drink too much. Equally, Gill’s drinking escalated from the strain of seeing Mum’s health decline. Gill herself said as much, though competing culprits were Wynn (a rotten husband), me (a neglectful and indulged brother) and Dad (a tyrant who went and died on her). And of course her eyesight was deteriorating. She was lonely, unhappy and had two kids to bring up. Who’d not get drunk given all that?

We pitied her and we blamed her, both at the same time.

People talk of drinkers “drowning their sorrows”. But Gill’s sorrows didn’t drown. They rose to the surface, blackly buoyant, while the good things went under.

I recently found in an old notebook that I was writing about Gill a year before she died in 2019, from heart failure during a binge. Was I already writing elegies for her a year ahead? I don’t credit myself with foresight. Death was a more likely outcome for her than for most people her age. And perhaps at some level I’ve always been writing about her. Still, it does feel a little eerie.

“What are you writing these days?” a friend asks. “No surprises there then,” he says when I tell him. “Ah yes, to complete the trilogy,” someone else says, more cynically still. Predictability isn’t the worst of it. In a creative writing workshop, we look at Kathryn Harrison’s memoir The Kiss, about her incestuous relationship with her father – a couple of the students find its confessionalism distasteful. That’s the accusation any memoir writer has to face: that to publicise difficult family stuff is mercenary, opportunistic and, worst of all, un-literary.

The accusation will be fiercer if you do it more than once. I am a serial offender.

I do sometimes ask myself: why are you writing this? It’s a sad story. Why bother? Then I think: if my parents’ stories were worth telling, why not Gill’s? Aren’t all lives, however damaged, of importance? Besides, what else would I write? For now it’s all I can think about. You don’t choose your subjects (or obsessions), they choose you.

Still, it’s a sad story, as Josie’s is too. She died self-destructively, eight months after discovering that my father shared her DNA, in 2005. I wonder why I’m so drawn to sad stories. Murder, death, grief: haven’t I had my fill? And what more is there to say? I like to think I’m a positive person. But darkness always seeps in. I’m like the poet James Thomson, setting out to write something cheerful but succumbing to the music of grief: “Striving to sing glad songs, but I attain / Wild discords sadder than Grief’s saddest tune … / My mirth can laugh and talk but cannot sing. / My grief finds harmonies in everything.”

After Dad died, I was consumed by grief.

After Mum died, less so – I loved her as much or more but I was prepared.

With Gill, I didn’t know what to feel – shock, obviously, but also a lack of surprise.

Is that why I couldn’t mourn her in the way I mourned them? Or because I’m older and more able to cope? To lose a sibling brings a different kind of grief, perhaps. You owe your existence to your parents. Your tie to a sibling isn’t foundational. However much you love them, they didn’t create you. They weren’t the ones who fed you, changed your nappies, bought your clothes, put you to bed, taught you to be good, punished you for being bad. And when they die, it’s the death of a peer, an equal, someone from your own generation. It’s terrible but less primal.

Did both my sisters kill themselves? It’s possible. Different circumstances, different methods and with different levels of conscious intent. You could say that the balance of their minds was disturbed or they’d not have acted as they did. But they resemble each other in their self-destructiveness, in leaving two children behind, and in having me as a brother. It doesn’t make me Ted Hughes. Still … Still.

No, I don’t feel like Ted Hughes must have done when his lover Assia Wevill killed herself six years after Sylvia Plath (lightning striking twice). But I do feel a little like Thomas Hardy after his wife Emma died, as if I should have made more effort towards Gill and Josie, rather than taking their presence for granted. In all the reading I did afterwards, it was a sentence in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park – “Fraternal love, sometimes almost everything, is at others worse than nothing” – that hit me hardest. To lose one sister may be regarded as a misfortune, to lose two looks like carelessness.

I think back to all those conversations I had with Gill about the past: whenever we spoke, we’d share some childhood memory. Was that because we found adult life difficult? Or because our childhood was so powerful and we so weak that we couldn’t let it go? Or because our childhoods, plural, diverged and we were searching for common ground? I’m stuck in the past, my wife Kathy sometimes tells me, as though affronted that the first 20 years of my life, before I met her, matter more than the decades we’ve spent together since. It’s not that they matter more, I say. And I don’t think I’m stuck. The point about revisiting the past is that you find new things each time you go there – things you missed or didn’t understand or failed to see the significance of, which as you get older you begin to grasp.

If I’m addicted to the past, I tell her, it’s because it hasn’t passed. I’m still there, still working things out.

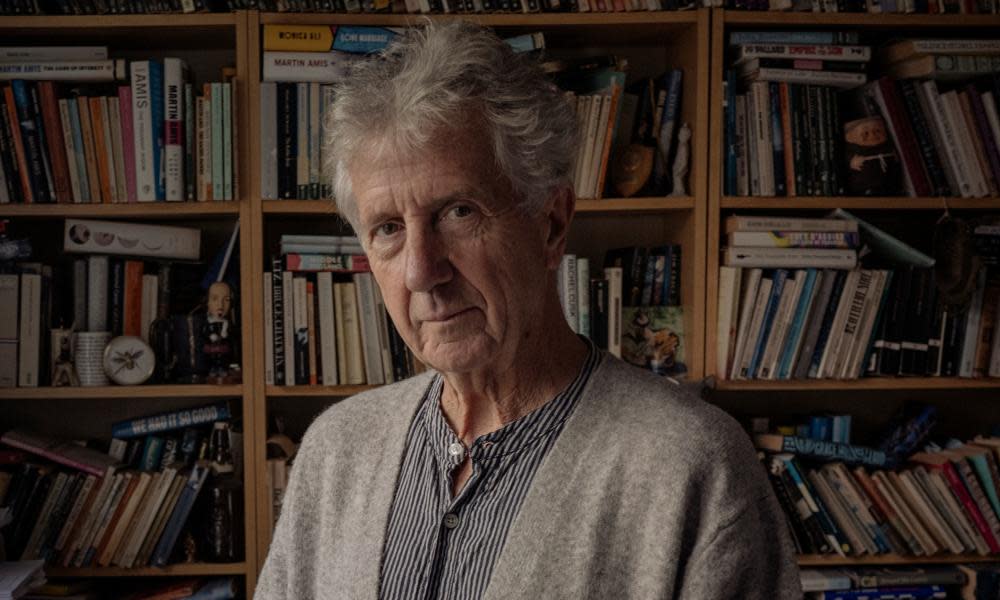

• This is an edited extract from Two Sisters by Blake Morrison, published by Borough on 16 February.

• In the UK, Action on Addiction is available on 0300 330 0659. In the US, SAMHSA’s National Helpline is at 800-662-4357. In Australia, the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline is at 1800 250 015; families and friends can seek help at Family Drug Support Australia at 1300 368 186.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies