'A black hole': How the state medical board bungled sex abuse cases for years

Note: This story contains graphic descriptions of reported sexual abuse that may be offensive to some readers or painful to survivors.

Operating in secret for decades, the State Medical Board of Ohio failed to properly investigate sexual misconduct cases, leaving serious abuse and even criminal behavior unaddressed, only sporadically referring it to law enforcement.

Voices of an untold number of victims went unheard, while others waited years for the board to take action including:

Two women accused a doctor of sexual assault, but it took the medical board four years to revoke his license while he abused another three women.

A patient accused a doctor of fondling, but the physician was allowed to keep practicing. Eight years later, the doctor cut a deal with the medical board, only admitting to “inappropriate boundary crossings.”

A grand jury indicted another doctor on felony sexual imposition charges, yet he remained licensed for five more years.

In the case of Ohio State University Dr. Richard Strauss, state officials called it a black hole — an inexplicable void at the medical board that allowed a sexually abusive doctor to slip through the cracks.

While state officials used that language to describe the Strauss case, medical board records show that similar inaction occurred with far more than one unscrupulous doctor. The records paint a picture of how the state’s system for investigating and disciplining doctors for sexual misconduct was riddled with inconsistencies that often-kept predatory doctors practicing and patients in vulnerable predicaments.

Despite credible evidence of wrongdoing in the Strauss case, the board’s investigation into the physician sat inactive for five years until the board closed the case. The board never disciplined him — never suspended or revoked his medical license. The board’s disregard of the allegations followed years of inaction by university officials to stop Strauss. Years later, the public would learn that Strauss sexually abused at least 177 former students between 1978 and 1998, with lawsuits indicating the number of victims was likely hundreds more.

>>Read More:What to know about Ohio State University athletic doctor Richard Strauss’ career, abuse and death

Today's medical board leaders said they've taken strides to improve their handling of sexual misconduct complaints, and have put new systems, people and processes in place to deal with such allegations and support the patients and victims who are affected.

But a Dispatch investigation into physician sexual misconduct claims in Ohio showed that the Strauss matter was but one example of the board’s failures over time to properly handle such cases and safeguard the public it is charged with protecting. Interviews with former medical board officials and a review of four decades' worth of the board's disciplinary citations paint a picture of irregularities, delays and secretive practices in its handling of physician sexual abuse.

Medical board pressure, policies hampered sexual misconduct investigations, former employees say

As part of its investigation, The Dispatch interviewed three former medical board employees who described systemic problems that kept many of the most-serious sexual abuse allegations from being examined.

The three former employees were involved in medical board investigations for close to a combined 20 years, and asked not to be identified for fear of retribution by board officials.

They described an agency with a lackadaisical and hesitant approach to sexual misconduct investigations and said officials made it difficult for investigators to do their jobs. They recounted policies that discouraged victims from coming forward and put pressure on investigators to clear cases quickly as well as a general lack of formal guidance regarding reporting potential criminal activity to law enforcement.

Each investigator typically juggled 10 to 15 cases at a time, they said. (Many of those cases related to other allegations outside of sexual misconduct, such as wrongfully prescribing or abusing prescription drugs.) And there was constant pressure on investigators from superiors to clear cases off their dockets as quickly as possible, the three former medical board employees said. They were specifically discouraged from diving deeper into sexual misconduct or abuse allegations because those cases would often take weeks or months to examine and cause a backup.

“I was good at doing in-depth investigations but I was told, 'Your reports are too long, you are spending too much time on these cases,'” one former investigator said. “I finally reached the point of, what are we really doing here? Are we really protecting the public or the doctors? It became clear to me it was the doctors.”

The former employees also described a lack of expertise among most investigators about how to handle sexual misconduct investigations. Most didn’t have law enforcement background or experience interviewing doctors accused of sexual misconduct, they said. Some were intimidated by the process and didn’t want to confront a medical professional about potential abuse. There was also a lack of specific training for investigators, they added, on how to handle the most-serious cases.

Board leaders acknowledged to The Dispatch that in the past, investigators might not have had the proper training and background needed for sexual misconduct investigations.

“Some of our folks didn’t want the confrontations they knew would come from accusing a physician of sexual abuse,” said one former investigator. “And many investigators didn’t have confidence that the board would back them up in those kinds of cases.”

There also was no clear guidance for when to contact or involve law enforcement in sexual misconduct cases, they said. Investigators would sometimes contact police or a sheriff’s office on their own. Other times, a supervisor might advise them to contact law enforcement but there were many allegations of sexual abuse or misconduct that could have been considered criminal acts that were never referred to law enforcement, the former investigators said.

Share your story with The Columbus Dispatch

Dispatch reporters will continue investigating doctor sexual misconduct and the State Medical Board of Ohio's handling of it over the years. Share your story if you're interested in having reporters look into it.

“The attitude by too many at the medical board was by contacting authorities you were just making our jobs harder," an investigator said.

In March 2020, the board added specific instructions in its investigator manual to notify law enforcement of allegations of any crime. Board leaders acknowledged that guidelines shouldn’t have been necessary — that criminal activity should have been reported to law enforcement all along — but this step took out any doubt about what to do.

During the past decade, board officials introduced other procedures or policies that made it difficult for investigators to do their job, the former employees said. For example, one rule that required investigators to meet with victims in neutral or public places discouraged many from wanting to come forward and share their story of doctor abuse because of the lack of privacy, the former employees said.

>>Read More:Strauss accusers call on NCAA, Big Ten to investigate Ohio State

"Those policies severely restricted our ability to do real investigations, period" said one of the investigators. "And in the opinion of a lot of us it was intentional by the med board leadership."

Medical board leaders did not dispute the allegations raised by the former medical board employees and acknowledged the shortcomings of its earlier approaches to sexual misconduct complaints.

The medical board also was more reluctant to elevate or prioritize allegations of sexual misconduct made against doctors working in large health care systems, employees said. The former investigators believed the board was more aggressive with independent doctors or those working in rural settings than those doctors working in health care systems who would be protected by legal teams with far more resources.

“We were the underdog because we were outmanned and didn’t have the time or resources or support from the board we needed,” said one investigator. “And believe me, the doctors knew this, especially the ones working in the larger health systems.”

The Dispatch reached out to three former executive directors of the state medical board, but none responded.

Current medical board Executive Director Stephanie Loucka said that if former employees know of physicians the board should have taken action on but didn’t, they should come forward to the agency with that information.

“That troubles me coming from former employees,” said Loucka, who took over the leadership role in 2019.

'It makes you lose hope'

In August 2006, a female patient reported that her physician, Dr. John E. Beathler, Jr. had inappropriately touched her genital area and attempted to stimulate her throughout a pelvic exam. She contacted the police, another doctor and the medical board about the incident shortly after it occurred, according to medical board records.

Available records give no indication that the board took any action until three months later in November, when a board investigator met with Beathler regarding the complaint.

By that point though, the Dublin doctor had allegedly assaulted another patient in a similar manner. Then, in January 2007, Beathler was accused of sexually abusing a third patient. A month later, the same medical board investigator met with Beather again.

In the months that followed, the allegations against Beathler came to a head at Central Ohio Primary Care, where he practiced. The medical director for the center began looking into sexual misconduct complaints against Beathler involving four of his patients. In June 2007, the medical director suspended Beathler from the practice, pending further investigation and contacted the medical board, records show.

But even as Beathler’s own practice took steps to keep him from seeing patients, the medical board didn't take action, records indicate. Beyond the two meetings between Beathler and the board investigator, available records shed no light on whether the board made any other attempts to stop Beathler from practicing between Nov. 2006 and when it finally began disciplinary action against him in 2010. By that time, he’d been accused of sexually abusing another two patients. The records provide no explanation as to why it took the board nearly four years to take formal disciplinary action against Beathler as complaints against him stacked up.

The board voted to permanently revoke his license in September 2011 for sexual assault allegations involving eight patients he saw between 2002 and 2010.

During his disciplinary hearing, Beathler acknowledged that he must have been doing some things wrong but suggested the incidents were due to his meticulousness in practicing medicine.

“I must be thorough to the point of fault,” he said, according to board records.

But Beathler’s actions — some of which might have been prevented had the board acted sooner — left harmful, lasting effects on his patients.

“It makes you look at all doctors differently, male or female,” one patient said during the medical board’s hearings on Beathler. The patient said she was abused by Beathler in July 2007, after the medical board was aware of other allegations against him.

“It makes you lose hope that someone in that profession, someone so highly esteemed, someone who you tell problems and issues to, that they can violate you in that way and in that manner and think nothing of it,” she said.

Complaints against doctors kept secret

In a number of sexual misconduct cases, details about doctors’ wrongdoing aren’t available to the public because of consent agreements between the board and physicians.

Rather than go through the board’s hearing process when confronted with an actionable complaint, a doctor can agree to certain disciplinary measures, such as surrendering his or her medical license, in lieu of a lengthy, formal investigation.

A doctor can negotiate the language and terms of a consent agreement, and unlike other cases where the public can access pages of supporting materials, these often contain much less detail.

There are a number of factors that often lead boards to settle with doctors, said Lisa McGiffert, board president of the Patient Safety Action Network. The coalition's work includes advocating to improve physician oversight and medical board responsiveness to patients and the public.

“They are overwhelmed. (Investigations) do take a long time. The cases are complicated, and the doctors always have better lawyers than the boards do,” she said.

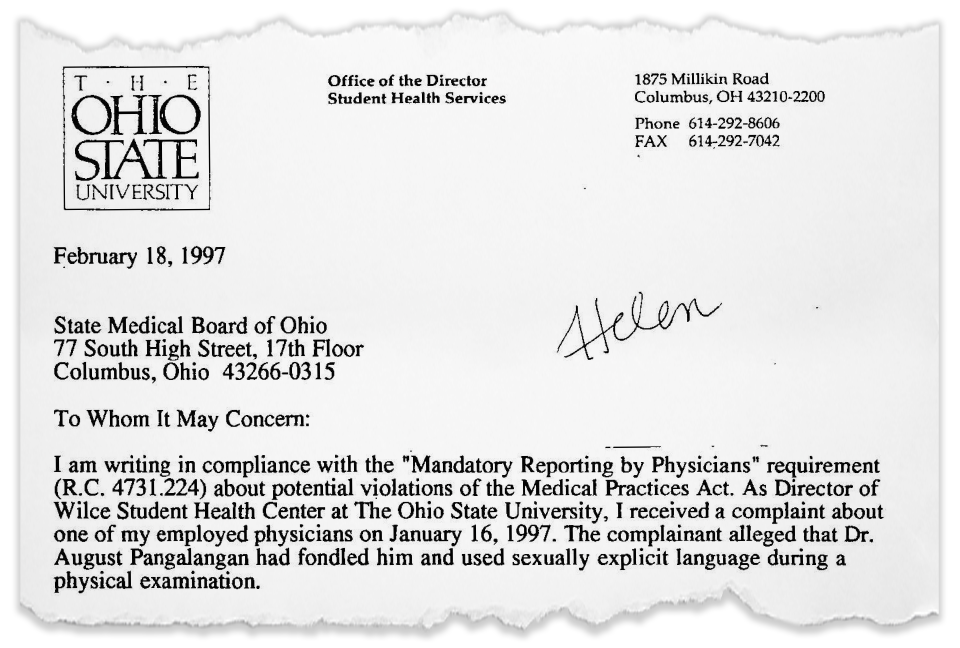

In The Dispatch's review of sexual misconduct cases involving 256 Ohio doctors, at least 73 cases involved consent agreements including one against Dr. Augusto Pangalangan.

In February 1997, the student health services director at Ohio State University notified the medical board of a complaint against Pangalangan, a physician at the university. The complainant alleged the doctor had fondled him and used sexually explicit language during a physical examination. The university added a warning letter to Pangalangan’s personnel file, but took no further action, as there were no witnesses and it was the first such complaint against the doctor.

>>Read More:Doctor who failed to report Richard Strauss abuse at Ohio State surrenders medical license

It's unclear whether the medical board took any steps to conduct their own investigation into the allegations against Pangalangan after they received the university’s letter in 1997. There was no record of board discipline against the doctor at that time.

Eight years later though, Pangalangan entered into a consent agreement with the state medical board, in which the board permanently limited his medical license so that he could not see patients.

Pangalangan admitted to engaging in “inappropriate boundary crossings” on at least three occasions involving patients while employed at the Ohio State student health center, according to the 2005 agreement. Details and dates of those incidents were not included.

Though his license was restricted, it was never revoked. He was still able to review files, charts and medical records of patients, though he couldn't treat patients or prescribe, order or administer drugs.

Pangalangan died in 2018.

It’s unclear how many total complaints might have been brought against Pangalangan over his career because the medical board only publicly discloses complaints when they lead to disciplinary measures,

Publicly disclosing the number of complaints against a doctor, especially when it comes to sexual misconduct, is incredibly important, McGiffert said.

So much of that misconduct often starts with gradual escalation and the grooming of victims, “So it starts slow,” McGiffert said. “Some of these complaints are low level complaints that are signals of escalation that might happen later.”

She added that if "we can’t see those kinds of complaints ... then you really can’t do a thorough analysis of what’s going on in the oversight and regulation of these professions.”

Medical board leaders said current state law does not allow the board to disclose how many complaints it has received about a doctor.

The board has also taken steps more recently to solicit additional complaints or information from members of the public if they believe they might have been a victim of a particular doctor, Loucka said.

“I think there’s an opportunity there for us to continue to look at how do we reach additional people,” she said.

When systems clash

Dr. Somnath Roy was arrested and indicted in November 2007 on more than a dozen counts, most of which involved sexual imposition charges related to his work in the medical profession.

Roy’s medical license remained unaffected until five years later.

During those years, as the doctor waived his right to a speedy trial and his criminal case dragged through the court system, Roy continued to hold full privileges at Elyria Memorial Hospital in northeast Ohio.

The medical board eventually suspended Roy’s license in December 2012, after he was convicted of six sex crime charges — four felony counts of gross sexual imposition and two misdemeanor counts of sexual imposition.

Present-day medical board leaders said they couldn’t explain why Roy’s case was handled the way it was. Historically, though, they said the board often found itself having to hold off on cases where law enforcement was already involved and let the criminal case play out.

That’s something they’re changing, former medical board president Betty Montgomery said.

“You will see, I think, a fairly dramatic change recently in (the board) saying we're going to respect law enforcement. We'd never want to get in the way of the criminal case, but at some point, we don't want the criminal case to get in the way with our job," Montgomery said.

Roy was sentenced to three years of community control and was required to register as a Tier 1 sex offender in Ohio for 15 years. He filed multiple challenges, and the Ninth District Court of Appeals reversed one count of felony gross sexual imposition. Roy has continued to challenge his sex offender registration, filing a motion as recently as December 2022.

Roy denied any wrongdoing when reached by The Dispatch. "I never did it. There was no proof, it was he-said, she-said …" Roy said. "It is complete nonsense."

His license remains permanently revoked in Ohio.

Montgomery and Loucka were hopeful that legislation introduced in the Ohio Senate last year would help make it easier for the board to take quicker action when a doctor has been indicted with a crime, rather than waiting for a conviction to trigger a license suspension or revocation. The legislation, Senate Bill 322, never came for a vote before the 134th Ohio General Assembly adjourned, but state leaders said they intend to try again.

Loucka and Montgomery said they expect that component of the proposed legislation will be a “tough climb,” noting that there will be examples of people who have been indicted but do not go on to be convicted.

“But we certainly think that, specifically with respect to some of these sexual misconduct cases that can be very complicated, that if we have this credible indictment, that the board has the discretion to be able to take an automatic suspension of that license,” Loucka said.

A 'new day' at the medical board?

Medical board officials have described a “new day” at the agency in recent years and new approaches for best handling sexual misconduct allegations.

“Sexual misconduct allegations and those that become cases are different (than other allegations),” said Loucka.

Changes the board has made in recent years include:

Developing a more-detailed triage process for when a sexual misconduct case comes in;

Adding two new investigators who work exclusively on sexual misconduct cases;

Creating a position for a victim advocate to support victims and guide through medical board processes;

Adding an attorney with a prosecutorial background in sexual abuse cases, who case investigators work with from the outset;

Creating a clear policy for when and how the board will notify law enforcement when it receives allegations about a licensee that are criminal in nature.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine also said the state has made some progress changing the medical board's historically passive culture in the last couple of years. That started with a working group that examined the state’s handling of the investigation of Dr. Richard Strauss and sexual misconduct allegations made against doctors dating back 25 years. At the recommendation of the working group, the medical board reviewed 1,254 closed sexual impropriety cases and re-opened 91 of them.

![Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, addresses Brian Garrett, not pictured, a sexual abuse survivor of Dr. Richard Strauss, during a press conference regarding a recent Ohio State University report about Dr. Richard Strauss on Monday, May 20, 2019 at the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, Ohio. Strauss, a former athletic department and health-services physician, is accused of abusing 177 male students from 1979 to 1997, the details of which were recently revealed in an Ohio State report regarding Dr. Strauss. Strauss killed himself in 2005 about a decade after retiring from the university with honors. During the press conference, Gov. DeWine signed an executive order creating a committee to examine an unredacted version of the Ohio State report which contained confidential information from a 1996 State of Ohio Medical Board investigation into Strauss. DeWine also called on lawmakers to review the statue of limitations for misdemeanor and felony sex crimes. Also pictured is Tom Stickrath, director of the Ohio Department of Public Safety. [Joshua A. Bickel/Dispatch]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/T_f_OA1aax0dq81rBkL4gg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY0MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/usa_today_news_641/1d84593b2388b35e0698b08c6ac2e284)

DeWine said his office helped the medical board add the former prosecutor and two investigators to specifically examine sexual misconduct cases. The governor said he has made it clear to the medical board that they need to ask his office for more legal personnel or investigators if they can’t keep up with sexual misconduct investigations.

While DeWine said he won't tell the medical board how to structure its staff, he said they should consider forming a standalone unit that would be dedicated to investigating the most serious sexual assault allegations.

>>Read More:Ohio medical board won't take action in most sexual misconduct complaints it reopened

"We have to make sure the medical board has the horsepower it needs," DeWine said. "We have to make sure the culture is right. … We have to make sure that they have investigators on staff who have experience … and they have enough of them so that they can make decisions based on what is right, not just on what is convenient."

Ultimately, transparency is a medical board's most powerful but underused tool in educating the public and sending a message to doctors, said McGiffert of the Patient Safety Action Network.

Being transparent shows doctors that "‘We’re not going to let you hide here anymore.'"

How to get help and report sexual abuse by a medical professional

▪ To file a report, call your local police or sheriff’s department.

▪ To file a complaint, visit the State Medical Board of Ohio online , or call the board's confidential complaint hotline at 1-833-333-7626.

▪ Call the Ohio Sexual Violence Helpline at 844-6446-4357.

▪ For a directory of rape crisis centers in each of Ohio's 88 counties, visit the Ohio Alliance to End Sexual Violence online.

▪ To speak with someone confidentially, call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 1-800-656-4673 or chat online.

▪ For more information on child sexual abuse, visit the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network online.

69842677007

- Embed

- Not set

- GM 2 OH

- Not set

- 01/25/23 9:44:46 PM

- Not embargoed

embed:

Return to Asset Tab

SEO Warning

Layout Priority

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Dispatch investigation shows medical board failed on sexual misconduct

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies