Black female artists couldn’t get into Crossroads galleries. They found an alternative

If you were looking to enjoy the work of Black artists in the Crossroads Arts District, you wouldn’t find yourself in your traditional fancy gallery.

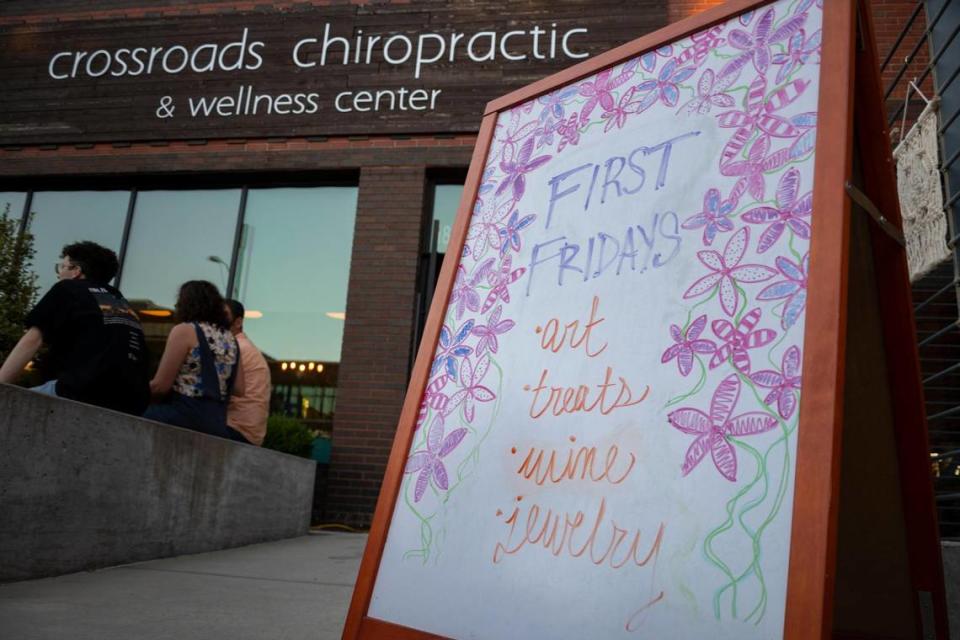

Try a chiropractic office.

Any given First Friday is an experience filled with music, street vendors and, of course, art. However, in a location long praised for its progressive and welcoming aesthetic, Black artists have been historically absent in Crossroads galleries.

As a result, for the second year now, a family of Black female artists, along with an assortment of vendors, unite to create a space for Black representation in the KC art scene.

“It has been very challenging for me, per se, in the Crossroads District, and I didn’t understand until I applied for probably three or four art galleries and got told no,” says artist and curator Christa Rice (known as Crissi Curly to followers on social media), who echoes several other local Black artists.

“For Black artists trying to break into the scene, things are harder. It is hard trying to find a place to show your art when gallery owners don’t think there is a market for your work.”

In addition to having a full-time career as a social worker for an adoption agency plus being a wife and mother, the 34-year-old Kansas City native has been working to shed light on emerging Black artists who lack exposure on First Fridays.

“I wanted to curate my own space since I wasn’t let into any other spaces,” she says. “To me it is so empowering. You don’t see our faces here at all. So, for the chiropractic place to give me an opportunity to show my art and then have my family come along and then bring in other people also means so much to me.”

Rice has put on over 50 exhibitions since 2016 to promote Black artists like herself. Last year, the owners of Crossroads Chiropractic, 1808 McGee St., offered her their location for a series of First Fridays shows. She jumped at the chance and is doing it again for a second summer and fall.

“Our relationship with Christa was pretty organic,” says Dr. Jessica Taylor of the chiropractic group. Rice was a patient, and Taylor found out she was also an amazing artist. She felt it would be a great opportunity to let an up-and-coming Black artist bring something new to the district.

“We thought it would be perfect to have her do a pop-up art show at First Fridays,” says Taylor. “From there, it just grew, mostly due to Christa and all her connections with other artists. She helped connect us with vendors and artists in the area and invited some of her artist friends and colleagues.”

For galleries, it’s ‘complicated’

Phillip Eirich of Cerbera Gallery, 2011 Baltimore Ave., describes the situation as something more nuanced. The gallery’s last show featuring Black artists was Kansas City Art Institute students last year.

“It is tricky,” he says. The show received positive press. But: “In the end we sold one piece. It was a really good show, but it is sad.”

Eirich, who sits on the executive board for the Kansas City Artist Coalition as well as the Crossroads Community Alliance, sees the issue less about race and more about finances. Galleries seek artists with a market to unload at least 60% to 70% of pieces shown on the gallery floor.

“For a gallery, the most important question is if they will actually be able to sell the artwork or not. More seasoned collectors are looking for resumes with more pedigree,” he says.

For many artists looking to make a name for themselves in the district, a lot of the success is also about the relationships a young artist can cultivate. According to Eirich, art shows are major commitments for galleries, not just in terms of money but also time.

“Let’s say we take 100 applications from artists. Only 5% or so would be considered a viable option to go forward and consider for an exhibition. These are relationships that are built over years before there is an actual belief a show will be a financial success for galleries and owners,” says Eirich.

One of the few local Black artists who exhibited work in the Crossroads is veteran painter Harold Smith. In 2018 he participated in a group show at the Leedy-Voulkos Gallery and a solo show there the following year. Smith remembers the struggle getting his work represented in the Crossroads. It is an issue that he doesn’t see changing soon.

“I would love if these galleries in Crossroads would take a look at Black artists and give them a shot. But I also understand that it is about money. Black art is often laced with social issues and commentary, and certain people can be turned off by that,” says Smith, who was recently part of an exhibit at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. His pieces appear in the Peacock television show “Bel-Air,” and he has a residency at The Studios Inc. Gallery, 1708 Campbell St..

Smith, a retired teacher who has painted professionally for over 20 years, believes until galleries in the district see Black art as more than a financial risk, there will always be a lack of representation.

“It has always been different for us, we just don’t have the same avenues. We have some incredibly talented Black artists like Crissi (Rice). The vast majority may be self-taught, but the veracity of the work is undeniable. It takes someone willing to take a chance.”

A family affair

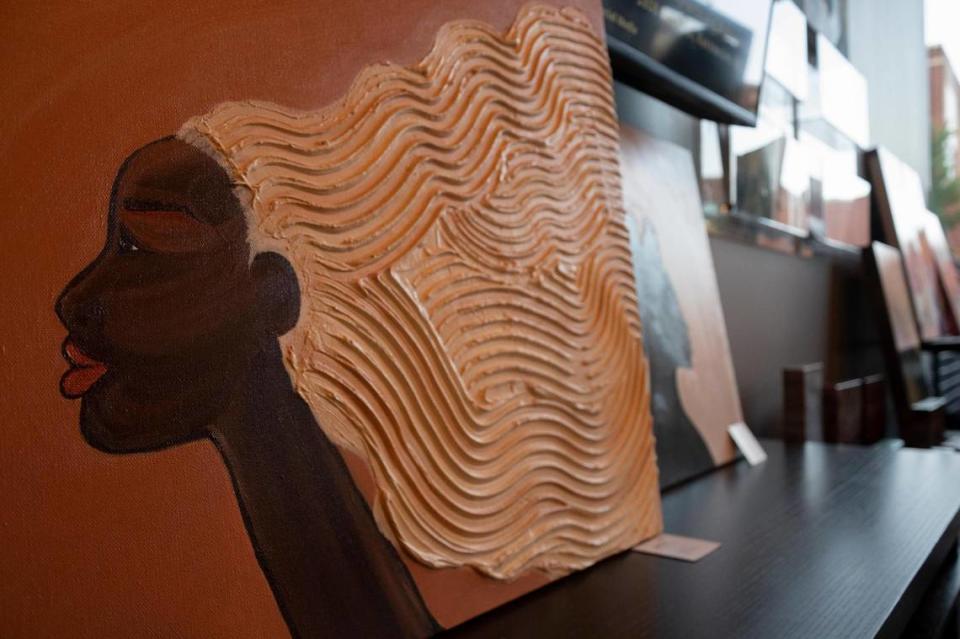

Rice specializes in a textured form of art, using different materials such as yarns to convey the three-dimensional range of Black hair.

“Society paints this picture that Black women do not have beautiful hair. You don’t see us in a museum as symbols of beauty or as muses,” says Rice.

Rice says she attempts to create pieces of joy instead of typical images of the Black body painted in struggle and hardship.

“I wanted to tell a story of how Black women are beautiful, and how our hair is gorgeous. We are made to feel our hair is not visually pleasing. When you do see Black women in art, they look rough,” she says.

Coming from a long line of Black female artists, Rice did not have to look far for talented painters with works waiting to fill the walls of Crossroads Chiropractic. Along with Rice’s own work, her shows feature art from her mother, sisters and her late grandmother.

In a way, these shows are a culmination of three generations of artistic women passing down a creative passion. For Rice’s younger sister, Kathrine Looney, this atmosphere of creativity led her into the arts at a young age. As a child, while most kids her age were watching “Sesame Street,” Looney found herself watching landscape artist Bob Ross.

“Some of my earliest memories was Saturday mornings when Mom would sit us down to watch Bob Ross. I was like, he does what Mom does, so let me listen to what he has to say,” laughed Looney. “He was like a magician to me. I would watch him make places I’ve never seen out of nothing on a canvas.”

Unlike Ross, however, Looney had a passion for capturing the beauty of the human form in her paintings through photo realism. She creates lifelike portraits, ranging from iconic album covers to her favorite actors like Jeff Goldblum.

“People are beautiful. I’ve always seen people as art. Everyone has nuances, personalities and features. My favorite thing about art is being able to do whatever you want. It’s up to you,” says Looney.

Their mother, Lolita Looney, remembers instilling a love and respect for the arts in all of her children at an early age. She has been painting since the early ’70s but confesses she never considered herself a real artist. It wasn’t until her children began to leave home did she begin to seriously explore who she really was as a painter. She is the daughter of two artists, yet found it hard to display her works.

“I didn’t enjoy art when I was younger because I was so critical and wasn’t creating because I loved it. I had anxiety, but you didn’t know what that was back then,” she says.

However, it was in her role working at the Nelson-Atkins Art Museum in the youth art program that she felt herself falling back in love with painting.

“It was not that long ago my kids left the nest and I asked myself, who are you? I began to really experiment and embrace my identity as an artist. I saw how the children in the program were so free. I wanted to show that creativity in my work,” says Looney.

A point of pride for the family’s art shows has been the opportunity to exhibit art from her late mother, Jolea Sears, who died in 2012. Until recently, her work went unseen.

“I am excited to display my mother’s art,” she says. “I am even more excited to show her art than I am my own. My daughters said we should honor her by showing her work. The satisfaction I get seeing my daughters present their art and seeing my mother’s alongside theirs is just amazing.”

Showcasing Black artists

While Rice’s First Friday shows may have started as a family affair, the Looneys have invited various fellow Black artists such as Taylar Sanders to join the lineup. For Sanders, who has been active in the KC art scene for several years, these shows are a welcome opportunity to get her work in front of new audiences. Sanders, like many Black artists using her craft to supplement her income, has gotten creative with how she uses her talents to bring in money.

“The art scene has been growing. I have seen so many opportunities for artists doing a lot of different things like paint-and-sip parties, portrait commissions, mural projects and children’s book illustrations,” says Sanders.

Sanders uses a variety of styles, such as portraits and landscapes, to, in her words, “transmute emotion by use of color.” As artists like Sanders and the Looney women venture out into the Crossroads art scene, they hope to expand into annual city art events, which also have a scarcity of Black artists, such as the Plaza Art Fair.

“It’s going to take us showing up and being present, even if we don’t feel welcome. I do, however, feel like it’s been more welcoming recently,” she says.

With no Black-owned galleries in the Arts District, Black artists may find it hard to get a foot in the door unless they were classically trained with a degree from an art school or their art has been exhibited around the country.

For many Black artists in Kansas City the Crossroads Arts District is the premier location for getting your art in front of major collectors. Unfortunately, for the majority of Black artists these opportunities for highly coveted spots in big name galleries are rare. While several galleries in the district have displayed work from a few Black artists over the past several years (many of which are visiting artists), the majority of Black artists surveyed by The Star do not feel there is adequate representation in the Arts District.

Rice has also reached out to local Black-owned vendors to set up in and outside the venue, including jewelry maker Shabazz Creations, gourmet cupcake baker Sprinkle of Sugar, and Radiate Body Essentials, to name a few.

Rice hopes that these displays in the district will help show white gallery owners that there is a market for Black art, and not just in the Black community. But creating a location where Black faces are normalized in the predominantly white arts mecca is a huge step forward in terms of opening up other elusive locations still not accessible to Black artists.

“I look at it from the standpoint that we are not accepted in certain places artistically in KC,” she says. “To be able to be in the Crossroads and having white people walk in and see the art is different from what they are seeing in other galleries down the street. We are hoping to bring something completely new to the scene.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies