Biden’s Supreme Court commission already facing resistance as it considers wide range of ‘reforms’

WASHINGTON – President Joe Biden's recently announced commission to study the Supreme Court is facing political headwinds before it convenes its first meeting, underscoring the challenge advocates for change have faced for years.

Dismissed by some on the right as an effort to "pack the court" with additional justices, the 36-member group also drew fire from some quarters on the left for its composition of academics, limited mandate and six-month timeline to finish its work.

“I am a little disappointed that the commission wasn’t given a mandate that says ‘come up with recommendations,’” said Gabe Roth, executive director of Fix the Court, a nonpartisan group seeking term limits for justices and greater transparency at the court. "I don't believe it’s that hard to come up with a consensus on core issues."

One of the central questions to be studied by the commission – whether to grow the size of the court – was dealt a political blow Thursday when liberal lawmakers proposed legislation that would increase the court from nine to 13 justices. Republicans and conservative groups erupted, and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., quickly undercut the effort by announcing she had no intention of bringing the bill to the floor for a vote – at least for now.

During his presidential campaign, Biden promised to name the commission as President Donald Trump and Senate Republicans rushed to confirm Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett before the election, giving conservatives a 6-3 edge at the court for the first time since the 1930s. At the time, Biden said he was "not a fan" of adding to the nine-member bench.

Biden signed an executive order April 9 that tasks the commission with studying the "merits and legality of particular reform proposals." The president didn't speak about the group and the White House declined to say when the commission will hold its first meeting, which would start the clock on its six-month deadline.

After that understated rollout, conservatives pilloried the plan. Carrie Severino with the Judicial Crisis Network said the commission was intended to "reward the liberal dark money groups" and predicted anything it proposed would "fit that political agenda."

"Nothing produced by such a far-left commission has any chance of passing," she said.

Though expanding the court is controversial, there has been bipartisan support for other changes to the federal judiciary, including the Supreme Court. Some of those ideas have been deeply intertwined with constitutional debates since the nation's founding.

Here are a few ideas the commission is likely to consider this year, starting with the most contentious:

Adding to ‘the nine’

Biden's order never mentions the fraught issue that was the genesis of the commission, a push to add justices to the Supreme Court. A White House statement made passing reference to the idea that the group will study the "membership and size of the court."

Advocates note that the court's size is set by federal statute, not the Constitution, and that the number of justices has changed. Opponents, including some of the justices themselves, counter that the court's size has been set for more than 150 years and adding seats would further politicize its work.

The court "is out of balance, and it needs to be fixed," Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass., said outside the Supreme Court Thursday. "Too many Americans have lost faith in the court as a neutral arbiter of the most important constitutional and legal questions that arise in our judicial system."

Adding to the court would offset the influence of its conservatives, including the three justices that Trump appointed. Expanding the court hasn't been attempted since President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and polls show it's extremely divisive. Biden has signaled he's not prepared to spend political capital on the idea.

"It would erode or denigrate the independence of the judiciary," said Paul Summers, a former Tennessee attorney general and co-chair of the "Keep Nine" Coalition, a group pushing for a constitutional amendment that would set the number of justices. "It would erode the checks and balances of the use of power on the other two branches."

A White House spokesman did not immediately respond to a request for comment, and White House press secretary Jen Psaki was noncommittal Thursday about whether Biden supports the idea of expanding the court. Biden, she said, would make up his mind after seeing the result of the commission's work.

"He's going to wait for that to play out and wait to read that report," she said.

Limiting lifetime terms

Federal judges, including Supreme Court justices, hold their office "during good behavior," a provision in the Constitution that has long been interpreted to mean lifetime tenure.

There is debate about whether that interpretation is sound – after all, the framers didn't explicitly use the words "life term" – and whether federal jurists could serve "for good behavior" for some period of time set by Congress. Some advocates have called for an 18-year term for any new justices confirmed to the Supreme Court.

"There's actually considerable historical support that what this means is they get to serve for the term of their appointment, and that term of their appointment could be decided by Congress," Leah Litman, a professor at University of Michigan Law School and a close observer of the court, said last week during a webinar hosted by the left-leaning American Constitution Society.

Nearly two-thirds of Americans support setting age or term limits on Supreme Court justices, according to an Ipsos poll published by Reuters on Sunday. Twenty-two percent of respondents oppose limits, and the rest don't have an opinion.

Proponents of the idea argue in part that a faster churn of justices would remove some of the political sting from confirmation battles since presidents of both parties would get more opportunities to nominate candidates. The average time on the bench for a Supreme Court justice has nearly doubled, from 15 years before 1970 to 28 years since then, according to Roth's research. The idea is not a strictly partisan one.

Chief Justice John Roberts, when he was an attorney in President Ronald Reagan's White House, opined in 1983 that setting a term limit of 15 years "would ensure that federal judges would not lose all touch with reality through decades of ivory tower existence."

Anthony Marcum, a resident fellow at the libertarian R Street Institute, argued term limits would raise the temperature of Supreme Court confirmation fights by more frequently lining them up in presidential election years. Under staggered, 18-year terms, he noted, a two-term president would pick 44% of the court's justices.

"Term limits don’t solve any problems surrounding the Supreme Court," Marcum said. He said advocates should focus on "increasing transparency" and ensuring that Americans – and lawmakers – understand the court's role as the nation's top judicial decisionmaker.

Ethics and recusals

Ideas such as a code of conduct or requiring justices to be more forthcoming about the reasons they recuse themselves from cases have generated bipartisan interest and would bring the court more in line with the other branches.

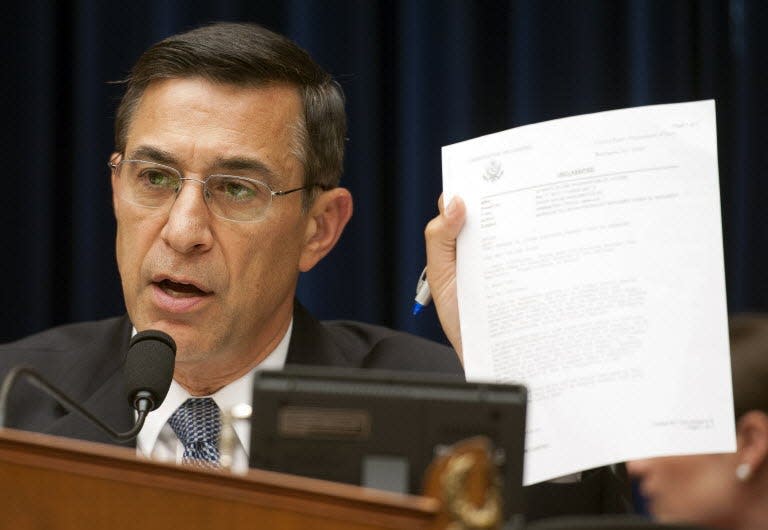

Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., sponsored legislation in 2018 that would mandate a code of conduct at the Supreme Court and require the justices to explain recusals. That bill drew bipartisan support, and some provisions have come back year after year. The sweeping voting rights legislation House Democrats passed last month included a code of conduct for the Supreme Court, but it's not likely to gain traction in the Senate.

"It's hard to believe that the highest court in the land doesn't have a code of conduct that the justices are supposed to abide by," Roth said.

Roth's group has raised concerns about several current and former members of the court, from Associate Justice Clarence Thomas' speaking at partisan events to Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's criticism of Trump, for which she apologized. Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Neil Gorsuch and Roberts haven't recused in cases involving interests they had a financial tie to, according to Roth's group.

Roberts asserted in a report in 2011 that Congress has no constitutional authority to impose a code of ethics on the Supreme Court, only on lower federal courts. Associate Justice Elena Kagan told lawmakers during a hearing in 2019 that Roberts was weighing a code of conduct for the high court, but it's not clear what, if any, progress has been made in the two years since.

Timothy Johnson, a professor of political science and law at the University of Minnesota, threw cold water on the idea of the commission's work leading to major changes, or even less controversial ideas such as a code of conduct. Such an effort, he said, could easily draw pushback from the federal judiciary.

"I don't mean to be a downer, but it has been accepted wisdom that the Supreme Court, because they are part of a co-equal branch, that they get to set their internal rules – period, end of story," Johnson said. "I could see Congress trying to pass laws (about recusals), but I could also see the court trying to strike that down as unconstitutional."

Cameras, lower courts

Biden's commission could delve into other familiar arguments, such as whether to further open access to the court's oral arguments. The justices have long resisted cameras and, until recently, balked at livestreaming the audio of their proceedings. That changed when the COVID-19 pandemic closed public access to the Supreme Court building. Arguments are conducted remotely with audio streamed on C-SPAN.

It's not clear whether that will continue once the coronavirus pandemic is brought under control.

Kagan told House lawmakers in 2019 that the justices hadn't discussed cameras as a group since she joined the court nine years earlier.

Another area the commission could explore: expanding lower courts. Trump and Senate Republicans had a considerable impact on the federal judiciary, appointing more than 200 judges to the federal bench. The Judicial Conference, the panel of judges that sets administrative policy for the courts, suggested this year adding 77 district judgeships and two appeals court judges to handle increased caseloads.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

Johnson speculated that Biden's best shot to propose major changes at the court came in the first weeks of his tenure, a time that was dominated by the pandemic and the crush of migrants seeking to gain entry into the USA. Now, he predicted, liberals seeking those changes will probably have to set the bar lower.

"I think they're going to build small and try to change the judiciary at the lower levels," he said, "and then hope Biden gets a couple of nominations over the next several years."

Related

Three Supreme Court justices tackle U.S. partisan divisions in public remarks

Biden unveils commission to study changes at Supreme Court after pressure from liberals

Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer pushes back on 'court-packing'

Biden to elevate potential Supreme Court nominee to high-profile appeals court

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: President Biden's Supreme Court commission is already facing headwinds

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies