Beekeeper turned spymaster searches for Iraq's missing Yazidis

He hasn't kept bees or sold honey in years and he's no longer living in Sinjar.

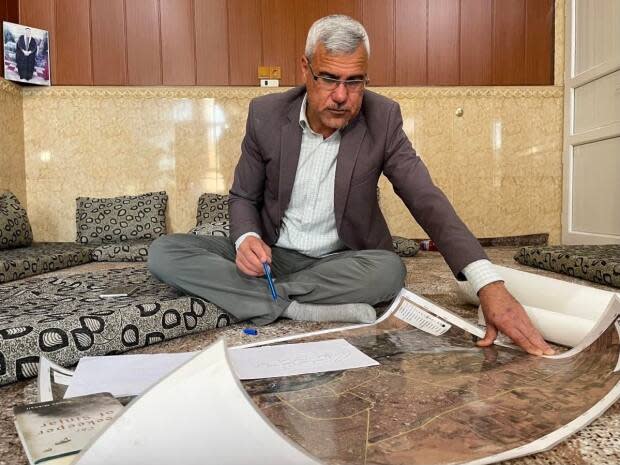

But Abdullah Shrem is still known to many as the beekeeper of Sinjar, his ancestral lands in the district of Sinjar in northwest Iraq. There's even a book titled after him.

In 2014, he parlayed his honey-buying contacts in neighbouring Syria into a network of potential saviours for Yazidi women and children enslaved by ISIS when it swept across the Yazidi heartland in northwest Iraq in August of that year.

Condemned as infidels by ISIS, thousands of men, boys and older women belonging to the religious and ethnic minority were slaughtered. The United Nations declared it a genocide.

More than 6,000 women and children were taken captive, according to the Kurdish regional government. Many of them were sold into sexual slavery or given to ISIS militants as rewards.

"When ISIS came, 56 members of my family were captured," Shrem said in an interview with CBC News from the village of Khanke, not far from the city of Dohuk in Iraqi Kurdistan, where he now lives.

"I never had a plan to rescue people, but it was the human thing to do and God helped me."

The 46-year-old says the first person he managed to retrieve successfully was at the end of 2014. It was one of his nieces. Word quickly spread and people started coming to him for help.

Shrem's business contacts in Aleppo advised him to get in touch with cigarette smugglers already risking their lives by moving goods forbidden by ISIS in and out of the so-called caliphate.

In other words, if they were caught, their punishment was always likely going to be death, he said.

WATCH | Yazidis struggle to rebuild Sinjar, Iraq:

Rescuers at work

Soon he had a network of informants.

"We were like an organized intelligence agency so that we planned and implemented our activities by ourselves," Shrem said.

Many of the captured women wound up in the Syrian city of Raqqa, a former ISIS stronghold.

Shrem rented a bakery there and turned the employees delivering bread to different neighbourhoods into his eyes and ears.

He also recruited a woman who went door to door selling children's clothing. Her access to the women of a household along with her presence of mind made it possible for her to ascertain who was a servant or a slave and who wasn't.

"People say that only men can do this job, but she had the most important role because she could easily go into houses," Shrem said.

He still has his original notebook with sketches and drawings of various extraction plans. One shows a series of headstones and instructions for a woman to visit a cemetery where a contact would be waiting.

He says they used the militants' own extremism against them.

"It was a positive for us that ISIS forces all women to cover their faces," he said. "If we wanted to rescue a girl aged 16, we created an ID for her and changed the age to 70 because ISIS wasn't going to remove the face cover."

His most challenging rescues, he says, were those involving four deaf and mute women. He videotaped relatives signing messages and instructions and then got them to the used clothes seller, who played them for the women. They all made it back to Iraq.

Some operations took months, he said, because the seller couldn't return to the same houses too often.

All in all, Shrem says he helped liberate 399 individuals. And the job's not over. An estimated 3,000 women and children taken by ISIS remain unaccounted for.

Many may well have been killed in the battles to defeat ISIS and the airstrikes that came with them, but Shrem believes some are still alive in Syria and in need of help.

"Yes, our activities are still ongoing," he said. "But the reality is that after the liberation [of ISIS-held territory], our tasks became much harder."

WATCH | Yazidi women face difficult choices: stay with their children, or return home?

Raqqa fell to the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) backed up by U.S. air power in the fall of 2017, but it was more than a year later that ISIS was finally defeated in Syria in the battle of Baghouz in the spring of 2019.

It's thought that many captive Yazidis might still be with ISIS fighters or families who escaped the final days of fighting in Syria, possibly to the city Idlib, where various Islamist groups are still fighting the Syrian regime, or to Turkey, where many ISIS fighters were recruited.

After seven long years, some of those taken as children may no longer remember who they are. Others were sent to indoctrination schools to be trained as fighters or suicide bombers.

Shrem admits that some women may have decided to hide their identities for fear of having children fathered by their ISIS captors taken from them.

The Yazidi spiritual council has issued a decree stating that women wanting to keep those children should be shunned by the community.

'The international community is not aware of us'

According to Shrem, one of the biggest problems in trying to trace missing Yazidi women is a lack of funds to pay ransoms and smugglers.

In the early days, much of it was raised through private donations. For a time, the Kurdish regional government's Office for Kidnapped Yazidis offered compensation for families who had to pay to get their loved ones back.

But that money has dried up.

"The problem is the international community is not aware of us, and up to now, the Iraqi government has not helped us or the missing Yazidi women," said Shrem.

He is both modest and matter-of-fact in demeanour. He enjoys explaining the complexity of the operations he spearheaded and is clearly proud of all the people he's managed to save.

But he also carries the weight of all those he couldn't.

Of the 56 members of his own family he sought to find and bring home, 16 are still missing.

Some of those helping in the search for the missing behind enemy lines also paid with their lives, including the woman who sold baby clothes. She was caught by ISIS and executed.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies