Australia’s indefinite detention of people with mental impairment breaches human rights, advocates say

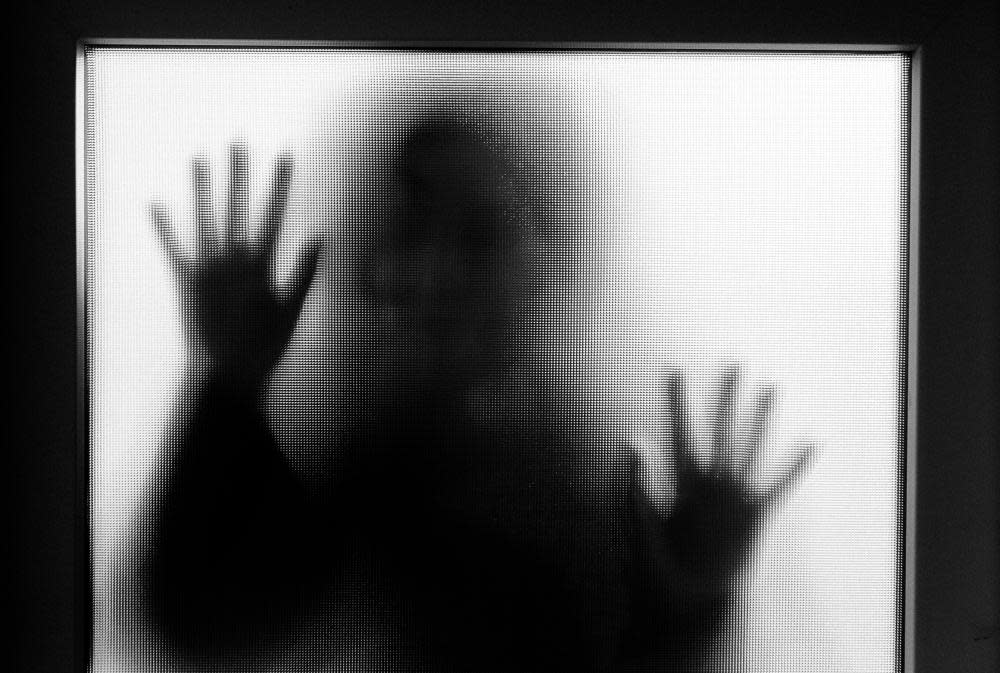

Australia’s use of indefinite detention for people with cognitive impairments is a breach of human rights and the “outrageous” failure to implement a proper monitoring regime is rendering people with a disability invisible from public view, experts say.

More than 1,200 people with a mental impairment are being indefinitely detained in Australia despite not having been convicted of a criminal offence. Each state and territory uses a variety of orders to enforce indefinite detention, including in prisons and hospitals.

In Queensland and the Northern Territory, such orders had been used to detain individuals for up to 42 years and 30 years respectively.

Experts and advocates say the system effectively “disappears” people with cognitive and mental impairment, particularly those without family, advocates, or lawyers.

Related: ‘Harrowing’ incidents of self-harm revealed among boys held at Perth adult prison

Data about the numbers of detainees, and why they are being held, is difficult to obtain. It is made worse by Australia’s failure, almost five years after ratifying the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture (Opcat), to establish a system of unannounced visits to places of detention.

Dr Piers Gooding, a senior research fellow at Melbourne University’s Melbourne Social Equity Institute, helped author a 2017 report into the indefinite detention of people with cognitive disabilities. The institute’s Unfitness to Plead project developed a pilot support program to assist accused persons exercise their rights, and identified ways to end indefinite detention.

“My concern is that that issue was raised almost five years ago, our two-year project concluded in 2017, there was a Senate inquiry, there were multiple other inquiries at a state and federal level, there have been numerous research reports … all calling for action on this,” he said. “And yet there really hasn’t been much movement on the government level.”

Gooding pointed to the case of Marlon Noble, a Yamatji man in Western Australia with intellectual disability, who was indefinitely detained in prison on sexual offences, after a court ruled he was unfit to stand trial.

Seven years later, a new psychiatric assessment found that he was, in fact, capable of standing trial. Prosecutors declined to proceed owing to insufficient evidence and he was released in 2012, after spending 10 years and three months behind bars without conviction.

Gooding said Noble was only freed after fierce lobbying by family and advocates.

Others in indefinite detention may not have such support, he said, leaving them invisible to the outside world.

“That, to me, is a complete failing of advocacy systems, human rights monitoring, and all of those things that something like Opcat would ideally prevent,” he said. “How can it just fall to those individual advocates to raise awareness of this? There should be a means to identify these people, to look at their case, and to see that the response by government has been appropriate.”

The United Nations subcommittee on the prevention of torture is due to visit Australia in October, which will put the indefinite detention regime under international scrutiny.

Related: ‘A disturbing picture’: use of excessive force endemic in Victorian remand centres, says ombudsman

Australia was supposed to have implemented a monitoring system to oversee all people in detention through the Opcat process. That process requires jurisdictions to set up independent bodies known as National Preventive Mechanisms (NPM) to inspect places of detention.

Three states – Victoria, Queensland and New South Wales – are understood to have told the federal government they cannot meet the Opcat requirements without more resourcing.

The federal attorney general, Mark Dreyfus, said Australia had received an extension for compliance with Opcat until January. The commonwealth’s NPM was already conducting inspections, he said, but only one state had delivered a fully operational inspection body as of July.

The issue was discussed at Friday’s meeting of the attorneys general. The various jurisdictions said they “noted the implementation of [Opcat] and the upcoming visit to Australia by the United Nations Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture, and agreed to continue working together on implementation of OPCAT in advance of the 20 January 2023 deadline for implementation”.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies