Anti-Asian hate won’t die with the pandemic. It’s as American as apple pie, unfortunately | Opinion

Asian Americans are being spat at, harassed, assaulted — and even gunned down. I’m saddened by the severity of these attacks, but I’m not surprised.

As a Chinese American living in the United States since 1949, I have seen a full spectrum of attitudes toward Chinese Americans. I have also felt the effects of attitudes toward other Asian groups, as we are often treated as indistinguishable by the Americans who target us.

This past year has seen some of the worst anti-Asian hate in my memory. As the specter of a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic grew, many reacted with fear and divisiveness. Officials, political parties and neighbors drew battle lines over shutdowns, school closures and wearing masks. But one thing united both sides — the certainty that China was to blame for the coronavirus.

Anger was aimed not just at China, but at the Asian-American community. According to a recent Pew Survey, 39 percent of Asian Americans reported people were uncomfortable around them, 31 percent experienced racist jokes or slurs and 26 percent felt threatened. In a study of 16 U.S. cities, the total number of hate crimes went down in 2020, but those specifically against Asians went up 149 percent.

After the Atlanta shootings last month, President Biden, Vice President Harris and other officials spoke out against the current wave of anti-Asian hate. The racism we face has gained attention. But, I worry it is not enough. I worry this racism will be blamed on the unusual circumstances or Trump’s “Chinese Virus” and “Kung Flu” rhetoric. I worry that when pandemic anxiety dies down, concern about racism against Asian Americans will die, too.

The blatant violence against Asian Americans might recede as the country recovers, but it will not be gone. And Asian-Americans will be waiting in fear for the next wave of extreme hate to strike.

While anti-Chinese hate has been exacerbated by the pandemic, this sentiment already was growing. In 2018, long before COVID-19, I no longer felt welcome in President Trump’s America. U.S.-China tension was growing. Trump’s racially tinged China bashing quickly translated to growing mistrust of Chinese Americans. However, he was not the first president to use anti-China rhetoric as a rallying cry to gain support, nor will he be the last.

There is still a strong bipartisan push in Congress to remain “tough on China.” The greater focus, one that will last long after the pandemic, is economics. During Japan’s auto boom in the 1980s, anti-Japanese sentiment surged, leading to the murder of a Chinese American. Today, China is seen as the main economic challenger. This bolsters a common theme seen in xenophobia and racism — the image of foreigners (whether U.S. citizens or not) stealing jobs from “true” — white — Americans.

Today, official rhetoric is not limited to specific trade practices or policy goals. There has been an increasingly broad focus on the Chinese Communist Party, ideology and worldview. China is being painted as diametrically opposed to the American model and leadership. Although aimed at the Chinese government, in practice such language hammers home an idea that the Chinese people are fundamentally at odds with American values.

This rhetoric heightens the view of Chinese as un-American, regardless of citizenship. Asian Americans already face racism and prejudices born from ignorance and founded in negative misconceptions about Asian culture, language and identity. Now, we are also subject to mistrust, questions about our values and scrutiny over our loyalties.

Racism that the Asian-American community is experiencing today is symptomatic of a long cycle of alienation, distrust and persecution. It often feels like our acceptance here is temporary and conditional. Asians have been targeted throughout U.S. history: the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882; the massacres of 1871 and 1885; the Yellow Peril; Japanese internment; the KKK’s targeting of Vietnamese after the Vietnam War — the list goes on.

The common thread is how quickly the Asian community in America is turned upon or used as a scapegoat. We are tolerated in Chinatowns, Chinese restaurants and other “acceptable” careers, and pushed into whatever mold suits the majority (in recent years the model minority trope has been a popular one). Then, if we try to step outside that box or if it fits the current political situation or social environment, we are attacked and no longer considered welcome.

Our voices are not often shared in American society. Our struggles are frequently sidelined as less important than other forms of injustice. We are left with a feeling of invisibility, forgotten and overlooked — until we aren’t. And when that happens, we are instead met with hate.

I don’t want my granddaughter to grow up in a world where she is considered less American than her neighbors. People are talking about anti-Asian hate now. The Asian-American community needs to seize this moment and keep the momentum going.

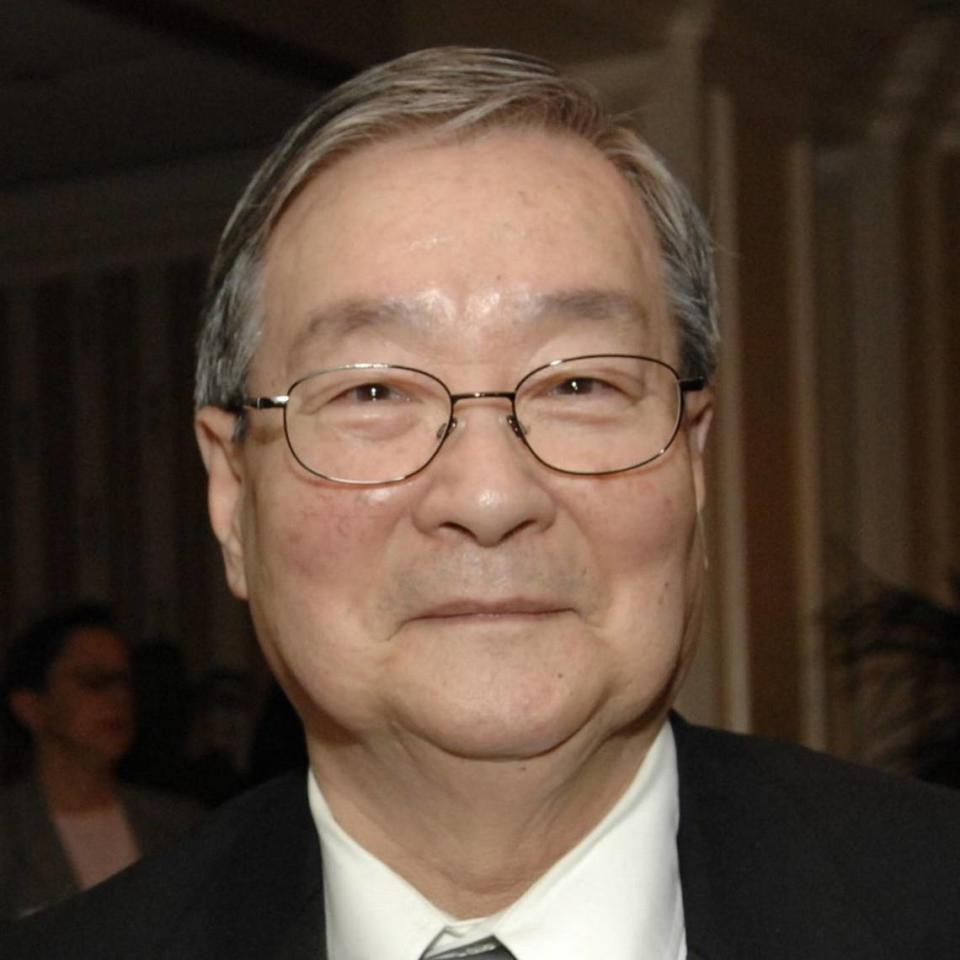

Dr. Chi Wang is the former head of the Chinese & Korean Section at the U.S. Library of Congress and is the co-founder and president of the U.S.-China Policy Foundation, an educational nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies