An ancient tale of kings and dragons gets new life in Kansas City with song and harp

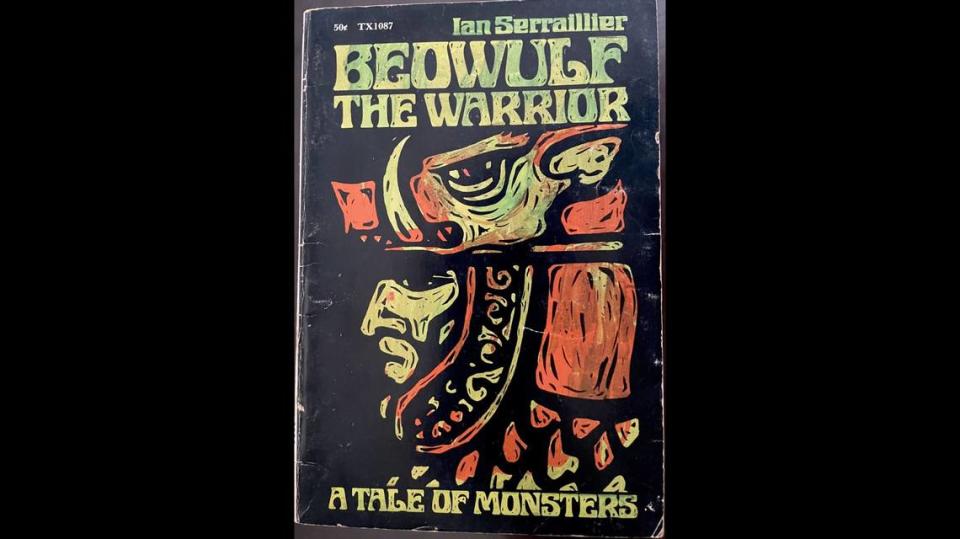

When I was a lad in grade school, I always looked forward to spending my hard-earned allowance on books from Scholastic Books. One time, a particular title caught my eye: “Beowulf the Warrior: A Tale of Monsters.”

As a monster connoisseur who had seen countless horror films and had an enviable collection of monster models and a subscription to “Famous Monsters of Filmland,” I snatched that book right up. I’ve been a “Beowulf” fan ever since.

The Friends of Chamber Music will present “Beowulf” as it might originally have been heard in an Anglo-Saxon mead hall from around the year 700 to 1000. Early music scholar Benjamin Bagby, accompanying himself on a five-string harp, will sing the ancient lay in Old English Oct. 29 at Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral.

Bagby was also introduced to “Beowulf” when he was just a kid.

“I think I was in seventh grade or something when a teacher handed me a modern English translation of ‘Beowulf,’ and she said ‘I have a feeling you’re going to like this,’” Bagby said. “And I did. I knew nothing about Old English or anything. I just read a great story, and that’s all I really knew. It had a monster, it had a dragon, it had a hero, it had a long-suffering king. All those things we love.”

Bagby was deeply involved in music from a young age. He was always focused on classical music, although it would take him a while to be introduced to early music, the field in which he is now one of the the world’s great experts. He spent his early years in Chicago, but when he was 14, his family moved to Prairie Village.

“By the time we moved to Kansas City I was really into opera in a big way,” Bagby said. “I’ll never forget a performance of ‘Ariadne auf Naxos’ at the Kansas City Lyric Opera. It must have been in 1965 or something. I really wanted to be close to it somehow, and I managed to get a role as a walk-on spear carrier. It allowed me to hang out with all the opera singers, which I thought was unbelievably cool.”

After his family moved back to Chicago, Bagby took part in a summer chorus in Michigan that was being conducted by Robert Shaw. Bagby was expecting to sing Haydn and Mozart, but he discovered the music that was to change his life. He took part in a workshop given by New York Pro Musica, America’s premier early music ensemble in the 1960s, and, as Bagby says, “my mind was blown.”

“They were performing 13th century French music and I was totally captivated,” he said. “I ran for the nearest library and found everything I could about these composers and this music. And, of course, as kids do, I started an ensemble. It was basically a high school garage band, only we played medieval music.”

Bagby eventually made his way to Europe to study medieval song on a fellowship, and he’s made his home there ever since. After founding the renowned early music ensemble Sequentia, Bagby made a series of highly acclaimed recordings, including the complete works of the medieval mystic and composer Hildegard von Bingen. But perhaps his most daring project is his one-man show of “Beowulf.”

“As I began working on medieval music and becoming more interested in where the roots of this might lie, in the early 1980s, I somehow put two and two together that the ‘Beowulf’ text, which we think of as English literature, is not English literature,” Bagby said. “It’s a performance document.”

By closely studying the text and consulting storytelling traditions from other parts of the world, Bagby realized “Beowulf” was meant to be performed, sung while accompanied by a harp, not read as a poem.

“It has formulae, which come up over and over again,” he said. “That’s the improvising poet’s way of winning some time to think of the next thing he’s going to say. It’s kind of like in rap, you have formulae that you use and you have new stuff that you intersperse with it.”

Bagby set about creating his one-man performance of ‘Beowulf.” For his harp, he turned to an instrument maker who was working with an archaeological museum in Germany to reconstruct a harp from the Merovingian period, around the year 500 to 750. The instrument was found in an early 19th century excavation near Stuttgart. The museum gave the harp-maker all of their research and X-rays, their analysis of the wood and everything he would need to make an accurate reconstruction.

“He made one for me and he made another one and he made another one and made another one” Bagby said. “So I have four of his instruments. There’s one that I’m particularly fond of because it’s quite stable, and that’s the one I’m playing in Kansas City.”

Beowulf the character has qualities that today would be considered, shall we say, off-putting. One of his “virtues” which is lauded throughout the poem is “lofgeornost,” being most eager for praise.

“Everybody feels it but they don’t talk about it anymore,” Bagby said. “In a preliterate society with no writing and no documents, the only thing that survives you is your reputation. You don’t leave behind any photos, you don’t leave behind any money, you don’t leave behind any mementos. What survives is your reputation. Beowulf was driven by his need for praise but also for his need to be remembered. And I think we all want to be remembered.”

Even with supertitles in English, one would think that in a world inundated with tweets and TikTok videos, a guy singing in Anglo-Saxon for more than an hour, accompanied only by a five-string harp, would be a hard sell. Bagby says that when people give “Beowulf” a chance, after 15 minutes they’re hooked.

“It’s a bit strange at first,” he said. “Then they settle in, and people shift into a slower gear. It calls up childhood associations of listening to adults tell stories. ‘This is going to be great. He’s going to scare me to death.’ Entertainment today is always clobbering us over the head with way overdone everything. Let’s just go back to a guy telling a story while plucking some strings made of sheep intestines.

“People have told me that they could have listened to it go on forever. I take that as the biggest compliment.”

7:30 p.m. Oct. 29. Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral, 415 W. 13th St. $25-$40. 816-561-9999 or chambermusic.org.

KC VITAs Octoberfest

St. Mary’s Episcopal Church downtown was built in 1887 in the neo-Gothic style. The church definitely has a goth vibe. It’s a place where Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde might have stopped by for Evensong. St. Mary’s, in fact, has a reputation for being haunted. Yes, I love this church.

KC VITAs conducted by Jackson Thomas will be hosting its Octoberfest choral concert in St. Mary’s on Oct. 29. In addition to atmospheric music, Charles Everson, the St. Mary’s gracious pastor, will be sharing stories of the church’s haunted past.

It will be a Night of the Living Composers, as the candlelit concert will feature newly written works appropriate for All Hallows Eve. After the concert, Bavarian pretzels, beer and other spirits will be served.

7 p.m. Oct. 29. St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, 1307 Holmes St. $15-$20. kcvitas.org.

You can reach Patrick Neas at patrickneas@kcartsbeat.com and follow his Facebook page, KC Arts Beat, at www.facebook.com/kcartsbeat.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies