Ambivalence about the Queen seems modern – but it’s actually a Victorian feeling

When the machine begins to break down, nobody is spared: even in the most majestic corporeality, bones ache, muscles weaken, tendons hurt, joints creak. Walking, previously a thoughtless activity, now needs deliberation and strategy. Longer lives and longer reigns merely postpone the process. Aged 96, and with “episodic mobility issues”, the Queen this week used a motor buggy to get around the Chelsea flower show; her arthritic great-great-grandmother, Queen Victoria, aged 78 at the time of the diamond jubilee in 1897, toured her own garden party in a horse-drawn carriage, literally talking down to everyone she met. “Drove about my guests, to many of whom I spoke,” she wrote in her diary, “but I could not see many whom I wished to.”

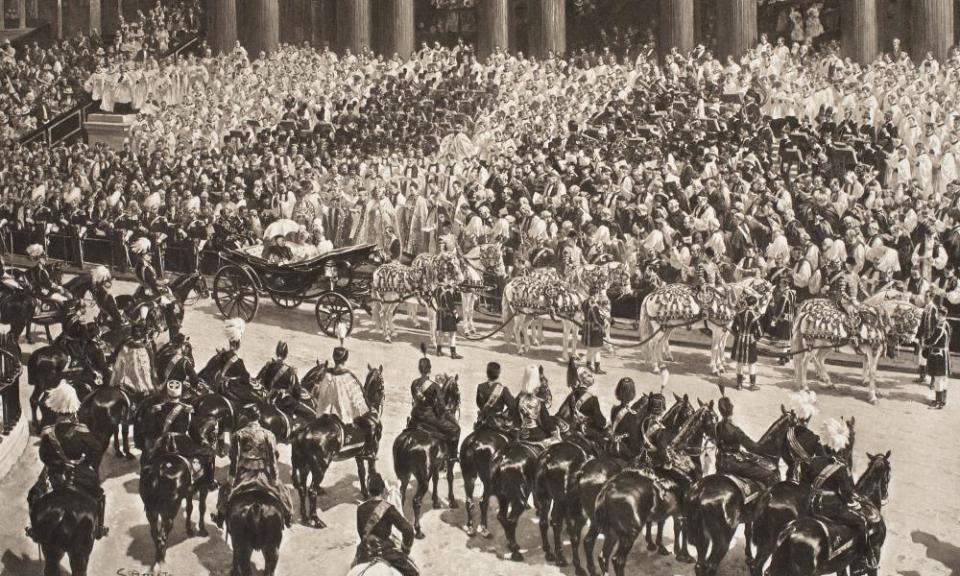

An even bolder innovation had been planned for her. The diamond jubilee had at its heart a magnificent procession of 50,000 imperial troops, who marched or rode from Buckingham Palace by two separate routes converging at St Paul’s for a thanksgiving ceremony that praised the Lord and blessed the Queen. The procession was spectacular. Britain had seen nothing as dazzling in its grandeur and variety before, and never saw it to quite the same extent again. This was peak empire. Hussars from Canada, Hong Kong policemen in conical hats, Indian lancers, Dyaks, Maoris, cavalrymen from New South Wales: it was said to be the largest military force ever assembled in London, and behind it in her carriage rode a little old woman, bowing and smiling and dressed modestly in grey and black. Mark Twain, there to write about it, thought that “she was the procession herself” and all the rest, spurs, men, rifles, gleaming helmets and trotting horses, “mere embroidery”.

There had been a problem, nonetheless. The Queen was too arthritic, too lame to climb the cathedral’s steps. The solution first proposed was to build a wooden ramp that would allow the carriage and its contents to be dragged up the slope and into the cathedral, and there parked centrally beneath the dome. But the Queen had vetoed the idea. Instead the service moved al fresco. The carriage remained at the foot of the steps and the Queen remained inside it, surrounded by the country’s political and clerical establishment, to hear prayers and the music provided by 500 choristers and two military bands.

“A never-to-be-forgotten day,” Victoria entered in her diary. “No one ever, I believe, has met with such an ovation as was given to me passing through those six miles of streets … The crowds were quite indescribable, and their enthusiasm truly marvellous and deeply touching.” The Daily Mail thought the same. The sun had stood in heaven for many millions of years, the paper wrote, but never before had it “looked down … upon the embodiment of so much energy and power” as that wonderful procession. Every line of the Mail’s jubilee issue was printed in gold ink and many of them celebrated what the Mail called the GREATNESS OF THE BRITISH RACE.

Some good work was done that today might usefully be repeated. The Princess of Wales (later Queen Alexandra) inaugurated a charity intended to provide a series of diamond jubilee feasts for London’s poor. Sir Thomas Lipton, the Glasgow grocery magnate, started the fund with a £25,000 donation, and by the end of the scheme about 400,000 people served by 10,000 waiters had consumed 700 tonnes of food, including lots of roast beef and lamb, veal and ham pie, pickles, dates, and oranges, all washed down with English ale or ginger beer.

Beneath the general mood, however, lay pockets of dissatisfaction and unease. (Like the Daily Mail and arthritis, the metropolitan elite is always with us.) The painter Edward Burne-Jones thought the dreadful boasting in the newspapers – “all this enthusiasm spent over one little unimportant old lady” – might prompt a chastising thunderbolt to fall on London. Hubris was easy to detect. Kipling’s poem Recessional, published a few weeks after the celebrations ended, gave the jubilee a doleful postscript: “Lo, all our pomp of yesterday / Is one with Nineveh and Tyre”. “Imperialism in the air,” Beatrice Webb noted, “all classes drunk with sightseeing and hysterical loyalty.” Her fellow socialist Keir Hardie saw the celebrations as no more than superficial theatrics. The cheering millions would cheer just as lustily for the president of a British republic; the soldiers were there because they were paid to be there, and probably found their duties irksome. “Royalty to be a success should be kept off the streets,” Hardie decided. “So long as the fraud can be kept a mystery, carefully shrouded from popular gaze, it may go on.”

Hardie’s view was a blunter version of Walter Bagehot’s dictum about the dangers of letting daylight fall on the “magic” of monarchy – a worry that grew the more powerful newspapers became and the more the monarchy depended on them for favourable publicity. A subtler witness to public attitudes – and, perhaps, a better guide to the monarchy’s future – was the London schoolteacher Molly Hughes, whose two ostentatiously radical friends (what was Victoria to them but a mere mortal?) went to the trouble and expense of hiring rooms in Cheapside from which to watch the parade. Hughes was astonished by their inconsistency, and to discover that “at heart they were as conservative as anyone and almost fanatically loyal to the queen, whose joys and griefs they had always seemed to share”.

That kind of ambiguity has sustained the monarchy during my lifetime, and I’m as prone to it as most people I know. This week I went to Fortnum and Mason in Piccadilly to look at their souvenirs for the platinum jubilee, which are very prettily got up and astonishingly expensive: £100 for a pudding plate, £12.95 for a tea towel, £200 for a 1.2kg box of chocolates. They bore no relation to the trinkets that came home to Scotland from the coronation in 1953, brought by an older cousin who had travelled south to see it: a little gold coach pulled by horses, and two or three toy soldiers wearing busbies or breastplates, sadly out of scale to the coach. That summer, variations of this combination must have fought battles across innumerable living room floors.

At the village school we were given tiny volumes of the New Testament and snake-clasp belts in red, white and blue. On the day itself, 2 June, games were organised on the football field of the local army barracks. I was no good at games, and a photograph of the event catches me looking away from my schoolmates towards something out of the frame. My buck teeth are prominent, and I have never looked at this picture without a stab of retrospective pity. “Buck teeth, buck teeth” was the taunt that followed me for several years, until they were fixed.

Last week one of those teeth snapped off: a minor symptom of the machine breaking down. In the dentist’s chair, having my root canal prepared for a replacement, I thought: “I had that tooth longer than the Queen has been on the throne.” A bizarre calculation. The fact I made it is evidence of her mysterious, inconstruable, possibly regrettable but certainly indisputable role in the way British people imagine themselves. It shouldn’t be underestimated. Victoria lay dying four years after her diamond jubilee, and in Lytton Strachey’s words “it appeared as if some monstrous reversal of the course of nature was about to take place. The vast majority of her subjects had never known a time when Queen Victoria had not been reigning over them.”

When the present Queen’s turn comes, be prepared.

Ian Jack is a Guardian columnist

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies