Achievement gap in standardized testing was growing. COVID added fuel to the fire.

Students who score the highest on national tests have been making academic strides over the past decade, while those who score at the bottom are struggling, according to a new brief.

The trend is a particular concern for high-poverty schools, where achievement levels tend to be low and students are still struggling with the compounded traumas of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts said.

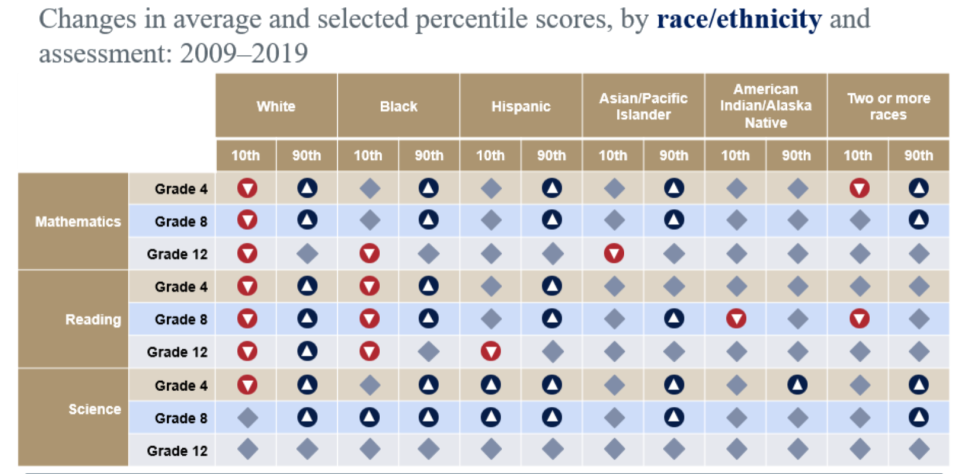

But it's far from the familiar achievement gap narrative: Scores for low-performing white students declined in more assessments compared with their Black and Hispanic peers, for example.

The brief, obtained exclusively by USA TODAY, shows scores for students performing in the bottom percentiles on the National Assessment of Educational Progress fell between 2009 and 2019, while those for students in the top percentiles increased or held steady. The test is administered periodically by the U.S. Department of Education.

More recent data from other standardized tests suggest low and high performers continued to pull apart during the COVID-19 pandemic – especially in reading. Results from the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress are set for release in a few weeks.

“This is an alarming, alarming trend and it can't go unnoticed,” said Beverly Perdue, former governor of North Carolina and a member of the National Assessment Governing Board, which published the brief. “It cuts across all spectrums.”

Struggling students need more help

The National Assessment of Educational Progress is the only nationally representative exam for grades four and eight that allows for comparisons across all 50 states and across groups of students over time. It also assesses 12th graders in some states. On average, the brief shows, overall scores didn't change much over the decade starting in 2009.

Yet math and reading scores for fourth, eighth and 12th graders in the bottom 10th percentile significantly decreased in that period. Compared to scores from 2009, more students in 2019 were unable to perform at the "proficient" level, essentially indicating a lack of competence in the subject matter.

What offset their downward spiral was the ever-growing achievement of students on the other end of the spectrum: Among students performing in the 90th percentile, scores increased for most participating grade levels and subjects.

“If you just look at the averages, you don’t detect change,” said Ebony Walton, a statistician for the National Assessment of Educational Progress. “But when you look underneath the hood, you actually do see change. It’s not the magnitude that’s the story here – it’s the direction. We’re seeing these student groups separate.”

The pandemic likely accelerated these differences in achievement.

NWEA, a research and educational services organization that develops and administers a suite of commonly used assessments, found a similar pattern in its reading test data. During the pandemic, high achievers made gains in reading at a rate expected for their group as determined by pre-pandemic trends. Reading test gains for low achievers, on the other hand, fell short of expectations for growth.

“We have consistently seen over the pandemic that the gaps that were already there back in 2019 have only widened … pushing those low achievers further down below national averages,” said Karyn Lewis, the director of the assessment group's Center for School and Student Progress.

Chronic absenteeism: Schools struggled to track who missed class during COVID

Achievement gaps have historically been defined on the basis of race. Rarely have the country's schools been held accountable for addressing other forces that contribute to inequities in educational opportunity and achievement, said Alberto Carvalho, superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District.

“We have growing disparities in America and not all of those disparities are necessarily race- and ethnicity-driven,” said Carvalho, who also sits on the National Assessment Governing Board.

Roughly a third of low performers on the 2019 eighth grade reading test are white, compared with about half of the country's public school students.

Black and Hispanic children are and have long been overrepresented in the bottom percentiles. But it's white students who most reflect low performers' downward trend. Scores for white students performing in the 10th percentile dropped in math and reading for all grade levels measured.

Scores for low-performing Hispanic students, on the other hand, improved or remained the same in every grade level and subject minus 12th grade reading. Scores for high-performing Hispanic students also improved or remained the same in every subject. Similar trends were seen for Asian American and Pacific Islander students.

Black low performers also held steady in their scores on the fourth and eighth grade math tests.

Some other noteworthy statistics among students who performed toward the bottom on the 2019 eighth grade reading test:

About 60% have parents who graduated from college.

Roughly 80% speak English as a primary language at home.

Why the gap is growing

Why are low and high performers pulling further apart?

It’s impossible to say for sure – the data only show what’s happening, not why. But researchers and educators pointed to growing concentrations of wealth and poverty as one possible driver.

Economic segregation in schools has worsened in recent years, and achievement has always tended to be lower in high-poverty schools.

Among that sample of eighth graders who performed poorly on the 2019 reading test, more than two in three were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. (A little more than half of the nation's public school students are considered low income.)

Susanna Loeb, an education researcher at Brown University in Rhode Island, suggested the trend could also be partly reflective of the backlash against No Child Left Behind, the national education law implemented under former President George W. Bush in the early 2000s.

One of No Child Left Behind’s stated missions was to elevate the achievement of low performers – and, in that sense, it likely worked. In the early 2000s, the gap between low and high performers closed. But No Child Left Behind also relied heavily on testing as a means of holding schools accountable for improving student achievement, leading to the backlash.

As No Child Left Behind was phased out, many schools started to distance themselves from such high-stakes testing, which, Loeb said, may have inadvertently contributed to low achievers’ further decline. Schools didn't have as much data to identify and better support students who were struggling to understand content and skills.

The communities are side by side: They have wildly different education outcomes – by design

At the same time, parents of many high achievers – who are more likely to be affluent and white – have spent more and more on academic enrichment such as tutoring.

These students may have been held to higher standards in the classroom while benefitting from greater investments in resources that support their learning.

Compared with teachers of high-performing students, those whose students received a low score on the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress were less likely to ask their classes to engage in “higher-order thinking” and offer them advanced coursework, according to one 2019 study.

Teachers whose eighth graders scored in the basic category in reading were more likely than teachers of higher performers to ask their students to summarize passages, for example, and less likely to have them identify main themes or scrutinize characters’ feelings and motives. Similar patterns were found among older students.

A body of research also shows that affluent – and, often, higher-performing – schools tend to receive more funding per student than lower-income, lower-performing schools.

Either way, Loeb cautioned against returning to the No Child Left Behind era and focusing exclusively on the lowest-achieving children.

Concentrating resources on any one group at the expense of others fails to address structural barriers such as generational poverty, Loeb said.

“Trying to push the bottom up is never going to help you on the top,” she said.

Stopping the 'one-size-fits-all' pipeline

For education leaders and researchers, ultimately the solution is deceivingly simple: individualize instruction as much as possible while holding all students to the same high standards.

Doing so is a daunting undertaking given how diverse low performers and their needs have become – especially when teachers feel stretched thinner than ever.

In Los Angeles, Carvalho said closing the gap is possible only "if we dare to dramatically shift the way we do things and stop putting kids through the one-size-fits-all, same-diameter-and-length pipeline." That means smaller class sizes and more support staff, from reading interventionists and tutors to counselors and social workers.

North Carolina's Perdue suggested a competency-based approach – in which students advance based on their ability to master a skill and not on their age or background.

Mississippi is somewhat of an outlier when it comes to its National Assessment of Educational Progress trends over the past decade, with its low achievers outperforming their counterparts nationwide on the 2019 fourth grade math and reading assessments. Carey Wright, the state’s schools chief, attributes that trend partly to its concerted focus on students in the bottom 25th percentile. The state also invested heavily in teacher coaching and professional development.

“There’s not one intervention for all students with disabilities, no one intervention for all children of color,” said Wright, who’s overseen the state’s public school system since 2013. “We’ve been relentless in our focus drilling down to the individual child.”

Contact Alia Wong at (202) 507-2256 or awong@usatoday.com. Follow her on Twitter at @aliaemily.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Standardized testing achievement gap was growing. COVID made it worse.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies