After 50 years of fixing shoes, ‘the Mayor of Short Street’ hangs up his tools.

No one has ever used “Apple Pay” at Tony’s Shoe Repair, nor has anyone pulled out a credit card. At least not successfully. No, for 54 years, Tony Likirdopulos has taken only cash or checks, dutifully entered into a 1927 cash register, where the numbers still pop up like a slot machine.

The University of Kentucky men’s basketball posters don’t come down; each one stays on the wall until next year’s team is tacked over top, a thick stack by now. The only UK poster that stands on its own is one of former Coach Tubby Smith, who used to bring his shoes to Short Street. The Atlas Finance Co. Personal Loans clock still keeps time behind dusty glass; just below it is a 1971 calendar.

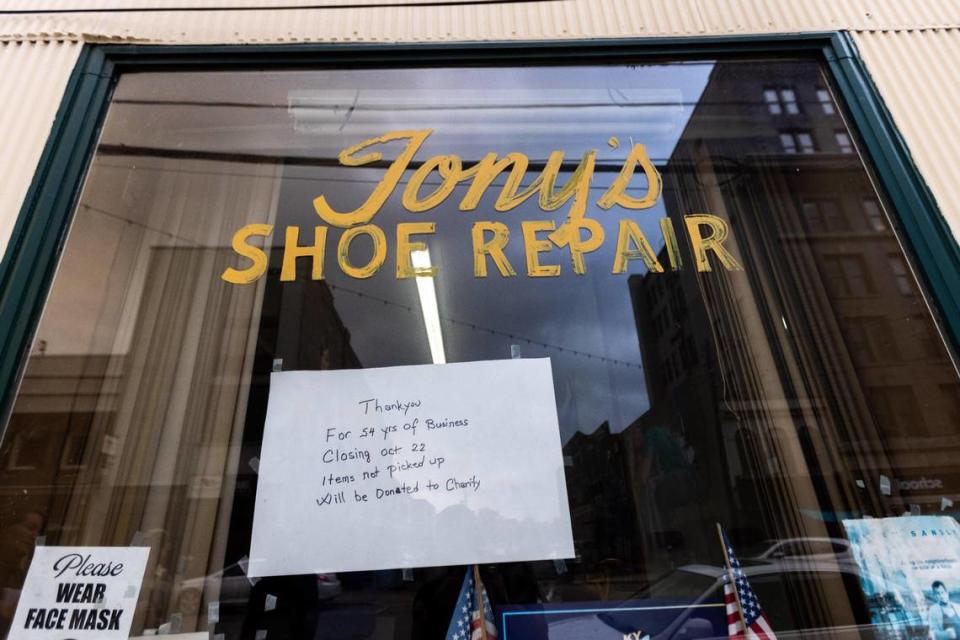

Do you sense a theme here at Tony’s Shoe Repair, those yellow letters first etched on the glass in 1968 and only slightly chipped today? Nothing has changed in a very long time, not the dingy once-mint green walls, not the pungent smell of leather, polish and the faintest whiff of feet, odors layered in the dust and the paint over decades. Nothing changes here until everything does, on Friday Oct. 22, when the 1968 Landis stitching machine is unplugged and Tony, now 80 is officially retired. The last shoes left behind will be donated to charity, and the next round of shoes that customers were still bringing on Thursday will go unrepaired.

“I don’t know what Jerry Tipton will do now,” Tony jokes about the Herald-Leader basketball writer and Tony’s Shoe Repair customer. “But I thank everyone. Good health.”

Tony is happy, he will go take care of his wife and see his granddaughters in Columbus more often. His customers are bereft at the thought of Short Street without him.

“It’s a tragic loss to the community,” said William “Sarge” Farris, who stopped by the store to say goodbye. “I don’t know what we’re going to do. He can never be replaced.”

John Harris brought a pair of leather shoes down to get resoled. He’s been coming to Tony’s since the 1990s, when he first moved here to work for UK. “He’s just a wonderful human being,” he said. “You can tell just from conversing with him.”

Left behind

Tony has conversed with thousands of people whose names he can’t remember and fixed thousands and thousands of shoes, although he never kept track of exactly how many. In an age when many flit from job to job, he has stayed in the same job in the same office for half a century beset by every disruption except the need to put new soles on shoes.

Tony shrugs and says, “I was trained to do this,” because his grandfather and father were also cobblers who made and repaired shoes on their native island of Tenedos, in what is now Turkey. All the stability represented at Tony’s Shoe Repair seems borne out of a central trauma in Tony’s life: an immigration story forced by geopolitical politics settled away from the vineyards and beaches of a small island close to the ancient site of Troy.

Tenedos started Greek, then became part of the Ottoman Empire in the 1400s. Amid a great deal of turmoil after World War I, the Treaty of Lausanne ceded control to Turkey. Although Greeks were allowed to stay, systemic discrimination meant most of them left for either Greece or America. Tony was forced to serve in the Turkish military on the Russian border between 1961 and 1963, but then his family had had enough. Part of Tony’s family went to Athens, another part to Chicago, where they had family. They left their homes, their businesses, their vineyards and land. Twelve days on a ship to land speaking Greek and Turkish but not a word of English.

“He’s very grateful, very appreciative of the community and the stabliity of it,” said his daughter, Christina Likirdopulos, a scientist who lives in Columbus and is the mother of Eleni and Alexa. “He was able to plant roots in Lexington because he had to leave everything behind.

“I’m pretty proud of him, ... I’m going to cry ... he came to this country as an immigrant with a dream of a better life, he only had a sixth grade education, because that was the circumstance of being Greek in Turkey for him. I knew my whole life that he always pushed me to invest a lot of time in my education because it would be a way for me to achieve the American Dream for us both together because he didn’t have the path for education. He worked hard my entire life.”

‘A charming experience’

Christina remembered stories about how public defenders would ask Tony for shoes because their clients didn’t have any for court, and he would give them some from the pile of unclaimed shoes.

Sometimes Tony would tell customers there was no point in fixing their shoes because they were simply falling apart.

“The quality is not there any more, shoes are cardboard that looks like leather,” Tony said. “If the foundation is good, you can do a lot with them.”

Tony’s store is a fixture of downtown, and of another era, a time before we went to superstores. We fixed our clothes, rather than throwing them away and buying new ones. We walked around our towns and got to know the butcher, the baker and the cobbler. For customer Erica House, “he’s like a dying breed of craftsmen.

“It’s an exchange, when you go in, he talks to you. He reminds us to slow down. Everybody who’s had an exchange with him knows what I’m talking about— it’s a charming experience and it will be missed.”

No one in Tony’s orbit seems to know if anyone else in Lexington actually fixes holes in shoe leather anymore. (In fact there is a Bluegrass Shoe Repair on Lane Allen Road.) There’s an opening in a storefront next to the Clock Shop in a very old building on Short. But how will they learn the basics?

“Ray Larson named me the Mayor of Short Street,” Tony said with a smile. “After I retire no one will want to be mayor anymore.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies