After 4 decades of influence, the ‘Godfather’ of Miami politics wants 4 more years

In the hectic moments after Miami commissioners fired the city’s prominent police chief, ending the latest power struggle at Dinner Key, some of Miami’s highest-ranking officials gathered in a small City Hall conference room to swear in Art Acevedo’s replacement.

As Miami’s new top cop began to give a speech, Miami Commissioner Joe Carollo, perhaps the person most responsible for Acevedo’s ouster, pulled out a cellphone and began to play a song: the theme from the epic Sicilian gangster flick, “The Godfather.”

Carollo now claims he doesn’t remember putting on the song. Maybe it was a poke at Acevedo’s regretful quip that the “Cuban Mafia” runs things in Miami. “Maybe it came from heaven,” Carollo said Friday.

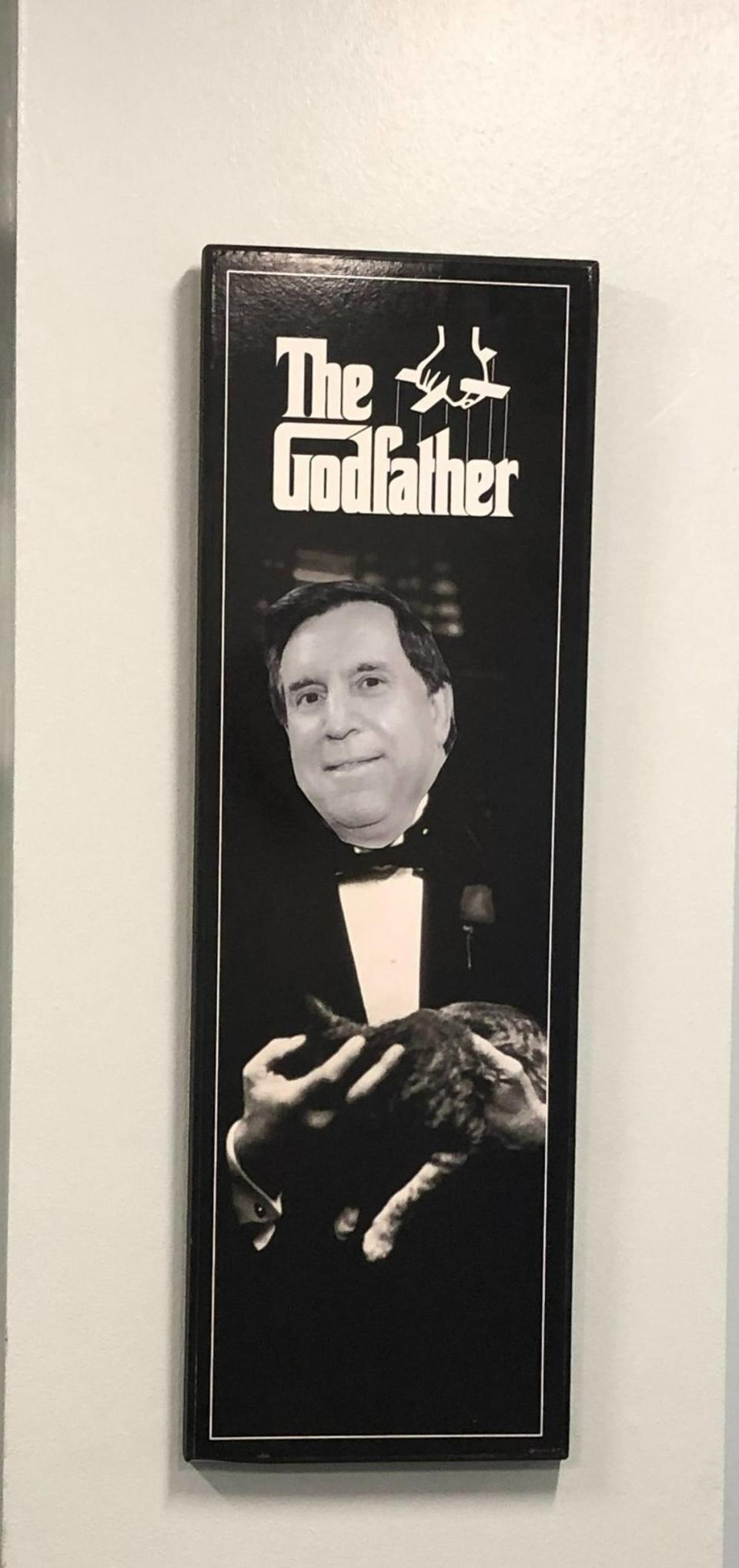

But the whole thing was captured by a city videographer. And if anyone was going to lean into a mobster joke, it was probably going to be the man who once hung a framed photo in his City Hall office of his head superimposed over “The Godfather” Vito Corleone’s body.

Off-and-on for more than 40 years, Carollo, 66, has imposed his will on Dinner Key, loudly warring with enemies real and perceived while beating back personal controversies and outlasting foes. And on the eve of a Nov. 2 election that could earn him another four years in office — and perhaps position him to regain his post as Miami’s mayor — Carollo’s ouster of Acevedo showed that some things in the Magic City still run through him.

“He has a street sense that’s very fine tuned,” said Roberto Rodríguez Tejera, a Spanish-language radio host on Actualidad 1040AM who has covered local Miami politics for over two decades. “He’s just like [Donald] Trump.”

With voting underway, and a staggering amount of money raised from special interests for a city commission race, Carollo is looking as politically strong as ever. Relying on a small but vocal base of voters in District 3, which includes Little Havana, The Roads, Shenandoah and a small part of Brickell, Carollo is running a familiar playbook that’s featured old-school attack mailers, Spanish radio ads and red-baiting television ads.

He faces three relatively unknown challengers, including a lawyer backed by the local Democratic Party who has represented members of Venezuela’s socialist government — a background that is easy fodder for a Cuban-born political strategist who seizes on any semblance of a tie between his opponents and leftist politics.

In the meantime, running against lesser-known, under-funded candidates hasn’t convinced Carollo to keep a low profile. Just in the past few weeks, he’s been the focal point of a $28 million lawsuit from Little Havana’s most popular club and gone to war with Acevedo, making a national spectacle of City Hall in the process.

“I am not going to shut up,” he said during a seven-hour Oct. 1 hearing, during which he suggested Acevedo might have him killed by police. “I don’t want to end up with a couple of rounds in me and a throw-down gun so somebody could say I aimed a gun at police officers and they had no other alternative but to shoot me.”

The lawsuit playbook

Carollo’s four decades of public life contain the kinds of ups and downs one would find on a streaming service, or in the political dossiers he so often compiles about his opponents.

In the ‘80s, as Miami’s youngest-ever commissioner, he made a name for himself as a combative aggressor who fought with other commissioners, the mayor, the city manager and police chief while warning of communist infiltration into Miami. After falling out of power, he successfully overturned the results of Miami’s 1997 mayoral election and became mayor by order of a judicial panel after proving absentee ballot fraud had tainted the results. As mayor, he was arrested on a misdemeanor domestic violence charge that was later dropped.

Carollo’s most notable attempt at civic life outside of Miami was equally dramatic, with his time as the city manager of Doral ending with his firing in 2014 after he claimed rampant corruption was tainting the city. (Carollo was later allowed to resign after he filed a whistleblower lawsuit and was reinstated by a judge.)

Carollo has been around so long that one of his most prominent political enemies, former Miami Mayor Xavier Suarez, is the father of the current city mayor, Francis Suarez.

And yet, much remains the same in Carollo’s platform, even after a 16-year hiatus from elected office following his loss in the 2001 mayoral election. The night he was first elected at the age of 24 in 1979, he told local NBC affiliate WTVJ he would give police “the moral backing they need to clean up our streets, to make our homes safe for our families.”

“Our people deserve to feel secure in the places where they live, and that they have a good quality of life,” Carollo told the Miami Herald in an interview last week. “This is why you cannot have a few that have taken advantage of our system and outright violated all of our code, building, zoning laws, doing whatever they please, destroying the quality of life for our people.”

Carollo, among the hundreds of thousands of Cubans who fled to Miami following Fidel Castro’s revolution, has always held himself up as a champion for the voiceless. After he won a seat on the city commission in 2017, he hung an old, framed photo of him as “The Godfather” — a tongue-in-cheek gift that nods to his Sicilian ancestry — in his first-floor office.

He has often found enemies to fight with, most recently going to war with the owners of Little Havana’s Ball & Chain.

After claiming during his 2017 campaign that the club’s owners participated in a covert plan to keep him from office, Carollo has focused the last four years on getting the city to identify violations at the popular nightclub.

In November 2020, city administrators agreed with Carollo. Officials shut down the nightclub due to fire safety problems that the owners deny they had. The club will soon reopen after clearing up their issues — and weeks after filing a $28 million lawsuit against the city that mentions Carollo by name a dozen times and references a memo Acevedo wrote alleging political interference in police matters.

Carollo filing and fighting lawsuits has been another constant during his most recent time in office. In 2018, Carollo sued his own city to stop a referendum that could have made Mayor Francis Suarez a strong mayor. The suit went nowhere. And in 2020, when Carollo’s opponents tried to have him recalled, Carollo resorted again to going through the courts to stop the effort.

In just one lawsuit by the owners of a Little Havana club, records show the city paid nearly $200,000 to defend him through April 2020, a figure that’s likely grown.

Carollo frames his battles as fights against insiders who flout the law. Carollo’s critics say he’s deployed the same tactics so long that people in Miami once horrified by his behavior have become desensitized to it.

“So many people have grown complacent. So many people have normalized him,” said Billy Corben, a Miami filmmaker who has become one of the loudest and most visible critics of Carollo and City Hall. “I think it’s extremely dangerous.”

History of feuds

Meanwhile, Carollo’s own record with top cops is uneven.

In 2000, incensed that no one had told him in advance about the federal raid to remove 6-year-old rafter Elián Gonzalez from his family’s Little Havana home to return him to Cuba, Carollo demanded that then-City Manager Donald Warshaw fire Police Chief William O’Brien, and then Carollo turned on Warshaw when he refused.

Some people were so disgusted with Carollo they flung bananas at City Hall in a crass reference to Miami as a Banana Republic.

O’Brien resigned, saying at the time he refused “to be police chief in a city that has someone as divisive and destructive as Joe Carollo as mayor.”

Yet Carollo can make allies out of enemies as much as he can make enemies out of allies.

Former Miami Police Chief Kenneth Harms, who led the department through the tumultuous 1980 Miami riots, had a longstanding feud with Carollo in the last years of his tenure. And in a strikingly similar move to Acevedo, Harms drafted a memo in 1982 accusing Carollo of seeking “to influence and pressure the police department for personal gain.” Part of his allegations included that Carollo was repeatedly claiming to fear for his personal safety and that he was “holding hostage” funds for police surveillance equipment because he was paranoid he was once followed by police during a background check.

Carollo, who was then a 27-year-old commissioner, responded to the allegations, saying at the time that “Harms’ main responsibility is to be a police chief and not a writer of novels of fiction.” Harms was eventually fired from the department in 1984.

Notably, Harms himself doesn’t think there are any similarities between that incident almost 40 years ago and Acevedo’s departure, nor does he harp on his muddy history with Carollo. In fact, Harms has decided to back Carollo in his reelection bid.

“I‘m not concerned with what happened in the ‘80s, he was a young man at that time, neither he nor I are young anymore,” Harms said in an interview with the Herald. “What I’m interested in is what he did in this go-around. I think that’s worthy of my endorsement because I think what he did ultimately culminated in Acevedo’s departure.”

Harms said he never made any complaints in the 1980s to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement about Carollo, which is what he said he would’ve done had he thought commissioners were doing something “inappropriate.” He added he thought Carollo did the right thing in airing past unpalatable incidents by Acevedo, whom he thought was not properly vetted when he was first hired.

Harms also criticized the memo Acevedo wrote before he was fired claiming political interference in police investigations by Carollo and the city’s two other Cuban-American commissioners.

“What I suspected that memo was designed to do was to be a ‘Hail Mary’ where you’re hoping to get some benefits,” Harms said. “I don’t find a lot of merit in it, quite frankly.”

Carollo’s long list of critics strongly disagree. Corben views the Acevedo episode as yet another police officer who has brought forward allegations against Carollo and other commissioners and has personally suffered the consequences of challenging his authority.

In his most recent act to get under Carollo’s skin, Corben turned to Carollo’s 2001 arrest on a domestic violence charge, for which he spent one night in jail. Corben hired a van with loudspeakers blasting the 911 call from Carollo’s daughter that night to drive in front of City Hall, and down Calle Ocho, in front of Cafe Versailles and Domino Park.

“He was pretty adamant about reading a dossier going back decades on Art Acevedo and I thought it only appropriate with ‘Crazy Joe’ on the ballot, that his residents be reminded” of his domestic violence incident, said Corben, using the sardonic moniker that Carollo’s detractors have deployed for decades. “There is no bottom with Joe Carollo.”

Carollo dismissed Corben’s commentary, calling him a “pay-for-play tweeter terrorist” whose opinions will have little impact among District 3 voters, many of whom get their news from Spanish-language media. The commissioner reiterated what is publicly known about his arrest: that the charges were dropped and he passed a polygraph test about the incident.

“I did not ever lay a finger on my ex-wife. The only thing that I did was a small cardboard tea box was thrown at the wall by me, and apparently she moved her head and it grazed her a bit,” he said.

Focused on issues

Carollo, unfazed by the criticism and insistent he rarely gets a fair shake in the media, says he’s focused on bread-and-butter issues facing his district. He says since his 2017 election, he’s pushed to replace aged playgrounds and upgrade playing fields at parks, purchased land for new parks and affordable housing projects and advocated for funding to hire more building and code inspectors, along with more resources to combat illegal dumping.

“District 3 has the least amount of parks of any of the districts. And we need to move forward on real affordable housing that’s needed,” he said Thursday, two days after the city broke ground on a 104-unit housing project called “Patria y Vida,” borrowing the name from the popular Cuban protest song and the movement it spawned.

He considers his sharp-elbowed approach evidence he’s willing to stand up to anybody, from code violators to developers to entities seeking city contracts, if it means the residents will benefit.

“My goal is to keep representing the people that haven’t had a voice,” he said.

Carollo’s opponents

With more than $1 million to spend, Carollo is a solid favorite to win the Nov. 2 election for District 3 and retain his seat, despite his narrow win four years ago against a little-known challenger.

Quinn Smith, the lawyer who is Carollo’s best funded opponent, has faced questions over his past work representing the Venezuelan government. Carollo’s other opponents are Andriana Oliva and gadfly Miguel Soliman.

On Friday, Smith said he respects voters’ reactions to his past legal work, where he represented people picked by Venezuelan ruler Nicolás Maduro to serve on the board of the directors of Venezuelan-owned petroleum company Citgo, which is headquartered in the U.S.

When the U.S. in 2019 formally recognized Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s acting president, there was an international legal dispute over whether Guaidó or Maduro had authority to select Citgo’s board. Smith’s clients, the Maduro-backed board members, lost the case in Delaware’s state supreme court.

“I understand the tremendous pain that has been caused in places like Venezuela,” Smith said on Friday. “I don’t for a second agree with that, and I would never support such things. I don’t represent Venezuela anymore. I have no intention to do so in the future.”

As for the commercial Carollo’s campaign is running on Spanish-language TV highlighting the neon pink hammer and sickle that Smith last year said hangs in his living room, the challenger calls it “one of the best criticisms of communism I’ve ever seen.”

“It reduced communism to the cheap lighting that you see outside of a strip club,” he said, “and I think that’s brilliant.”

So far, Smith has received the backing of the Miami-Dade Democratic Party, whose chair Robert Dempster told the Herald in a statement that the committee did not think his past work with the Venezuelan government was disqualifying.

“Quinn has never hidden the fact that he has worked on international arbitration cases for the Venezuelan government and that he has never lobbied for it or defended it in human rights violation cases. Quinn is trying to serve his community and considering that he stands to rid the City of Miami of the tyranny of Joe Carollo, we wholeheartedly stand behind our endorsement,” Dempster said in a text message.

Given Carollo’s history of alleging leftist ties to his opponents, Smith’s candidacy looks a bit like throwing red meat to the incumbent. But Carollo’s critics say they’re determined to push him back out of power.

“I will try to use every resource, through my program, however I can, to make sure [Carollo] doesn’t win,” said former Hialeah Mayor Raul Martinez, now a political commentator.

“I was one of the ones who believed that Carollo would come back into office … and that he was different,” said Martinez. “But you can’t change a person like that, it’s impossible.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies