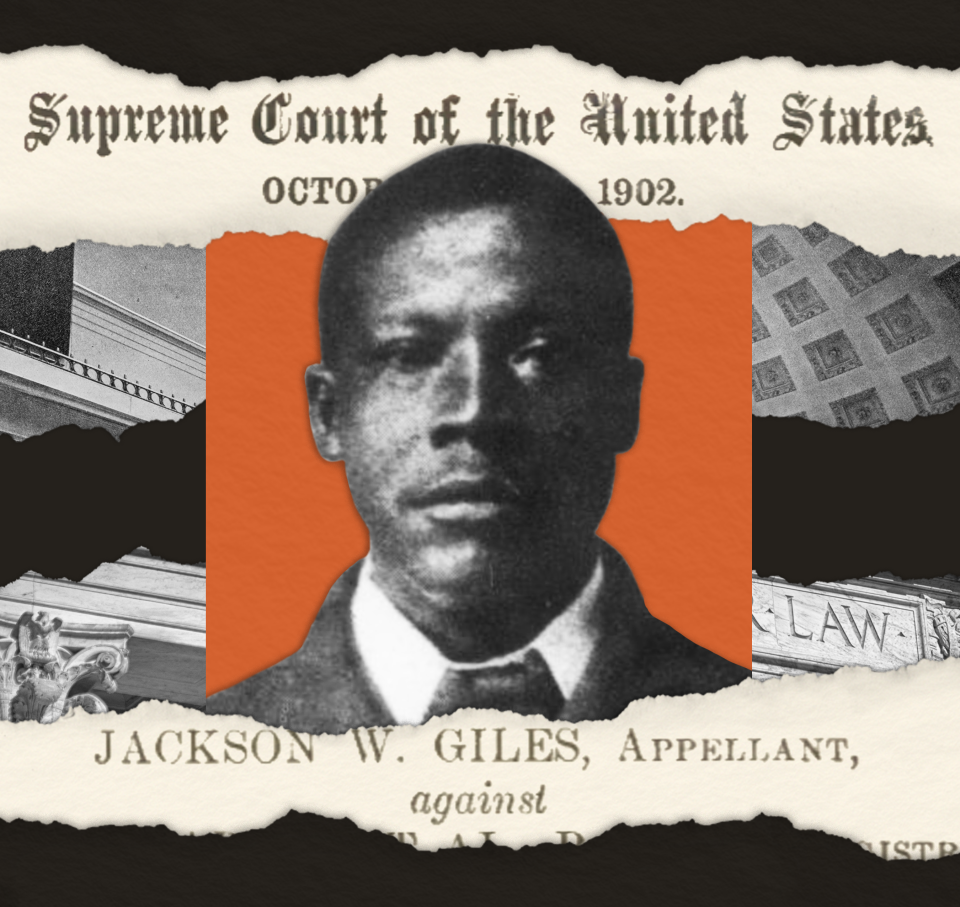

In 1902, a postal worker challenged Jim Crow Alabama. Jackson Giles fought for his right to vote

At the dawn of the 20th century, Dorsett’s Hall was a small island of freedom for Montgomery's Black community amid the toxic tides of Jim Crow. The three-story building on Dexter Avenue, a few blocks away from the Alabama State Capitol, hosted dances, organizational meetings and protests. On May 5, 1903, this refuge opened its doors to Black ministers, businessmen and editors from all over Alabama.

They came to support the Colored Man’s Suffrage Association of Alabama and its battle to restore their right to vote, after the passage of a new state constitution that violated the 15th Amendment's suffrage protections. Many had suffered humiliations at the hands of white registrars, like unanswerable questions or demands for letters from white men attesting to their good character. This last type of insult had spurred the leader of the association, who greeted the 150 delegates that afternoon. His name was Jackson Giles.

Giles, 44, had taken the state of Alabama all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, demanding the rights stolen from him and hundreds of thousands of Black Alabamians by the state's Constitution, enacted 19 months before. Giles had spent a year traveling, speaking and putting together what money he could to pay the attorney fighting the case – money that was augmented, with or without his knowledge, by secret payments from Tuskegee Institute President Booker T. Washington.

He lost. The courts had imposed $119.80 in costs on Giles, equal to about three months’ pay. But Giles made it clear to the delegates that day that he would not surrender.

“One more river,” he sang at the start of the meeting. “There’s one more river to cross.”

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

“The justice or injustice of the decision he said he would not discuss,” the Montgomery Advertiser, a white newspaper hostile to Black people, wrote the next day. “He said, however, that the fight was not lost as there are three more cases on the dockets of various courts … and he believed that on proper presentation before the Supreme Court of the United States, they would succeed in having an opinion handed down that the (Alabama) Constitution is invalid.”

Giles pleaded for donations from the group, urging them to keep up the fight. By the end of the day, he collected $55 for attorney fees.

Never Been Told: Filling in the history of the nation's people of color

Jimmie Lee Jackson: How a Black man’s death in 1965 changed American history

'Fabulous' Lena Richard: How a Black woman chef from New Orleans built a food empire

The legal team still had challenges to the state Constitution in courts, and Giles’ legal team would fight on. But the first case, Giles vs. Harris, put the final block in the rough marble edifice of Jim Crow, making legal challenges to voter suppression all but impossible for the next six decades. If 1896’s Plessy v. Ferguson laid the foundation for the South’s apartheid regimes, Giles v. Harris fortified them against political attack. The case and the events around it are particularly relevant today as battles over voting rights and voting access consume Congress, state legislatures and the U.S. Supreme Court.

“It’s my view that Giles is more important than Plessy,” said Richard Pildes, a law professor at New York University who published an influential study of the case in 2000. “Jim Crow would never have been sustainable if Black adults continued to be able to vote, or it would have been much harder to sustain it.”

While legal scholars have become more interested in Giles v. Harris in the past few decades, the man at the center of the case has been overshadowed by the legal battle and Washington’s involvement in it. For years, Giles’ whereabouts after the case have been a mystery. Using interviews, newspaper archives and newly uncovered documents – including Giles’ death certificate – USA TODAY was able to reconstruct Giles’ life before and after his legal battle.

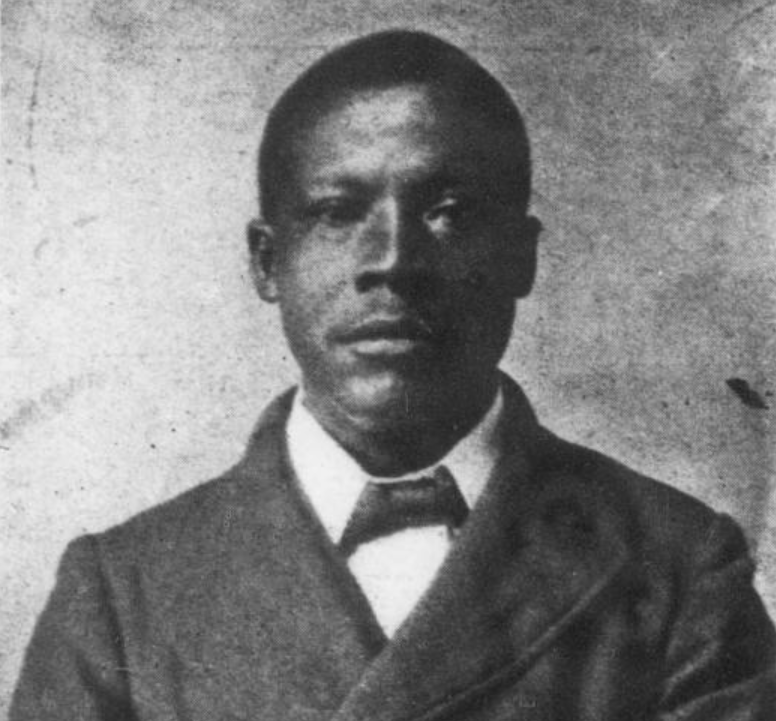

It was a life dominated by political activism, one that illustrates Black Southerners' often-ignored fight against the rise of Jim Crow. Giles was no naive dreamer, but a man with more than two decades of local political experience that he drew upon to battle the limits white Alabama wanted to impose on him.

And like many other Black Southerners, Giles would not submit to the victory of segregation. When he could no longer fight Alabama, Giles left.

The activist

Jackson William Giles was born in slavery on Jan. 4, 1859, on a 175-acre cotton plantation outside Rockford in Coosa County, Alabama. His father, Henry, was born in Virginia. His mother, Clarissa, came from Georgia. Both appear to have been victims of the Second Middle Passage, which over a century ripped more than 1 million enslaved Black Americans from their homes and families in the Upper South and transported them to cotton and sugar plantations in the Deep South.

After emancipation, the family moved to Montgomery, about 45 miles south of Rockford, in 1872. Henry worked as a gardener, Clarissa as a laundress. Jackson and at least two of his sisters went to school and learned to read and write. Over the next two decades, Giles pursued many different careers. He was a cotton factor – a middleman between cotton farmers and suppliers – a grocer and, on at least two separate occasions, a newspaper publisher.

But his focus was politics. By the 1880s, Black men no longer held federal or state offices in Alabama. They could still vote, but they often saw their ballots negated by violence or fraud. Yet they continued to organize under the Republican banner.

Carlos Bulosan: Author’s critique of America gave Filipino migrants a voice

Meet the ‘Angel of the Alamo’: Adina De Zavala’s grand stand in 1908 saved a landmark of Texas history

"People knew what was at stake," said Derryn Moten, a professor of history at Alabama State University in Montgomery who has studied the Giles case.

Giles was a regular face at Montgomery GOP meetings. He claimed to have attended every county GOP gathering in the 1880s and 1890s, and his colleagues sent Giles to a state Republican convention in 1884. But Giles and other Black Montgomerians also organized conferences focused on racial and labor issues, both major concerns for what was a working-class community. At one such gathering in 1888, Giles urged his fellow delegates to dig into their pockets to support the State Normal School (now Alabama State), which had lost its state funding.

By the 1890s, Giles was an officer at most public gatherings of the Black community, often handling fundraising. His party work landed him a position as a mail carrier in 1890 – a well-paying job for the time – and in 1898 got him a position as head janitor of the local post office. Giles earned $500 a year in the role, comparable to what skilled workers of the time made. He also served as a deacon at a Congregational church. In a 1903 profile, the Colored American, a magazine published in Boston, called Jackson Giles “a highly respected citizen” of Montgomery and “a race leader of the right sort.”

In 1900, Giles was named secretary of the National Negro Race Conference in Montgomery. The conference convened to address a serious issue: the Jim Crow state constitutions that were annihilating the rights of Black Americans throughout the South. Giles and other leaders signed a Declaration of Principles that, among other items, demanded that “the Fifteenth Amendment of these United States stand in its original integrity."

'What is it that we want to do?'

The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, forbids states from denying the right to vote based on “race, color or previous condition of servitude.” But by 1900, white Southern elites found ways around it. Florida approved a Constitution in 1885 that allowed the Legislature to impose a poll tax that fell heaviest on Black residents. In 1890, Mississippi enacted a new constitution – without voter approval – that used poll taxes, literacy tests and an electoral college model of electing governors to raise unscalable hurdles to Black political participation.

The Mississippi Constitution became a model for white supremacists throughout the South. It especially interested the Bourbon Democrats in Alabama, who had held power in the state since 1874.

In April 1901, fresh off a triumph at the polls, the Bourbons scheduled a referendum on a new constitution. As one white Alabamian said at the time, “We have disfranchised the African in the past by doubtful methods; but in the future we will disfranchise him by law.” The referendum passed, thanks to white planters in Alabama's Black Belt stuffing the ballot boxes. The following month, an all-white, Bourbon-dominated convention assembled in the State Capitol in Montgomery.

“And what is it that we want to do?” said John Knox, the president of the convention. “Why, it is, within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this state.”

The Constitution required all voters to register before Dec. 20, 1902. They had to be residents and had to meet poll tax requirements. The Constitution offered some exemptions for military veterans; the “lawful descendants” of those who fought in the wars (better known as a grandfather clause), and “all those of good character who understand the duties of citizenship in a republican form of government.”

On paper, this last provision seemed innocuous. In practice, Alabama gave registrars, who were always white, enormous power to decide what understanding the duties of citizenship meant. Another provision allowed the state to impose property ownership requirements for voting after 1903; this, combined with poll taxes, took the vote from both Blacks and poor whites.

Sent to a statewide vote, the Constitution was controversial, and some Bourbons opposed it. But it prevailed in the November election – again, thanks to fraud by Black Belt planters.

Despite the risks, Black men appeared in numbers to register to vote in March 1902, and white registrars were careful not to turn every Black applicant away. Teachers at Tuskegee were registered, as were a handful of businessmen.

But most Black men faced rejection and humiliation. White registrars accused Black veterans trying to register under the military provisions of the constitution of forging their discharge papers. Other Black applicants were asked unanswerable, nonsense questions, such as “what are the differences of Jeffersonian democracy and the Calhoun principles as compared to the Monroe Doctrine?”

Many registrars demanded that Black applicants bring statements from whites attesting to their good character. Giles and his colleagues at the Post Office faced this insulting requirement when they tried to register in March. Many Black Alabamians, including Giles, refused to suffer such indignities. Giles would later write that this humiliation led to his legal challenge.

The Colored Man’s Suffrage Association

Giles and other Black activists formed the Colored Man’s Suffrage Association of Alabama in late March 1902. Many came from the circle of postal workers, and some, like Giles, also held leadership positions in local Black churches. The association's goal was getting the courts to invalidate the voting provisions in the Alabama Constitution.

"At this point a lot of middle-class African American leaders realized they could not rely on Southern legislatures," Moten said. "They could not rely on Southern courts. Any favorable redress they would receive they would likely receive from the federal courts."

A circular written by Giles and the group's secretary J.S. Julian called on supporters to raise $2,000 ($60,000 to $64,000 in 2022 dollars) for the legal fight. Giles and Julian wrote that Alabama registrars had refused “some of our most worthy citizens, morally, financially, and intellectually, men who pay taxes on property from $500 to $30,000.”

“No negro’s testimony as to his good character is accepted,” the men wrote. “It seems that the presumption of the Board of Registrars is that no negro has good character.”

By the end of 1902, the association had raised about $1,500 (equal to more than $42,000 today). But that sum wasn't enough to pay the legal bills. That brought help from another quarter: Tuskegee Institute President Booker T. Washington.

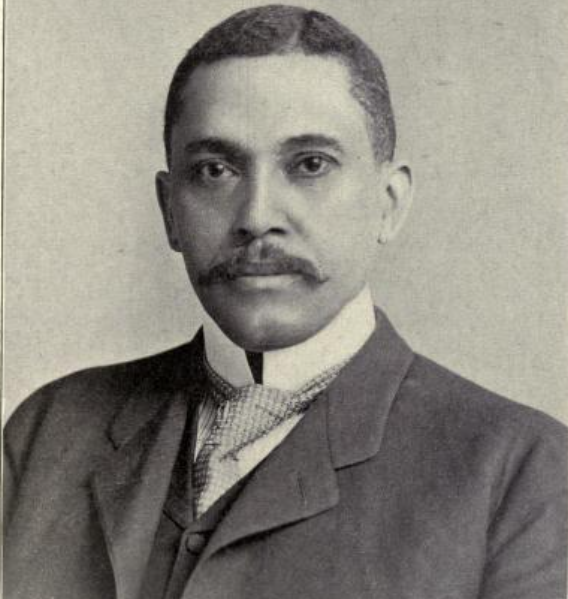

Washington’s 1895 “Atlanta Compromise” speech – in which he argued that Black Americans should delay demands for political and civil equality and focus instead on economic development – rocketed him into national prominence. His philosophy was controversial within the Black community and faced increasing challenges after the formation of the NAACP in 1909. But the speech won widespread approval from wealthy white people, including steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, who showered donations on Tuskegee Institute. Washington quietly poured much of this largess into legal battles over segregation and voting rights, and funding Black newspapers.

It’s not clear how Washington learned of Giles’ case, or how much Giles knew of Washington’s involvement in it. But Washington and Giles knew each other. As the publisher of a Black newspaper in Montgomery in 1884, Giles had taken advertising from Tuskegee and published praises of Washington, then just 28. Later, Giles served as president of an annual farmers’ conference at Tuskegee. The conference focused on agricultural matters, said Ray Smock, a biographer of Washington and co-editor of his papers, but also brought Alabama’s Black leaders together to discuss political problems and form strategies. Around the time of the Supreme Court case, Giles published a local Montgomery paper called The Pilot; Washington published at least one essay in it.

No full accounting of Washington's civil rights spending survives. It’s not clear why, but Washington may have wanted to avoid creating a paper trail that Alabama politicians could use against him.

“The South was a totalitarian system,” Smock said. “Nothing got away from white sheriffs and white newspapers. … They had to be careful.”

Washington assigned New York attorney Wilford Smith, a key aide, to Giles’ case in the spring of 1902. From his correspondence, Washington appears to have followed the case closely, but officially, the Tuskegee president kept his distance from it. Washington's secretary, Emmett Jay Scott, corresponded with Smith. Both men used code names in their letters on the Giles case, to hide Tuskegee's involvement.

“He’s not really in danger in Tuskegee, but he’s in danger in the rest of Alabama,” said R. Volney Riser, a professor of history at the University of West Alabama, whose book “Defying Disenfranchisement” includes an in-depth study of Giles v. Harris. “It’s not just danger to his physical person if something happens to him, it’s him, it’s his family, it’s his entire Tuskegee operations.”

Smith, a Texas native, faced many obstacles. He had few precedents to guide him. He had limited time to challenge Alabama’s anti-democratic scheme. And he faced dangers as a Black man pushing back against white oppression in the heart of Alabama. Three white attorneys once tried to ambush Smith in a Montgomery courtroom and hit him with a chair, and were stopped only when a judge got wind of the plan.

“Wilford Smith does not have staff,” Riser said. “He does not have junior associates who can do this. He is a practicing attorney … he is doing this completely on his own.”

The attorney settled on a strategy of speed. Smith filed multiple suits against the Alabama Constitution in federal and state court, with a goal of getting a case to the U.S. Supreme Court, the only venue where he stood a chance of victory.

“I think if I can get the present case to Washington, the matter will be settled,” Smith wrote to Scott on Sept. 15, 1902.

Smith got unexpected help for his plan from the Alabama Attorney General’s office. State officials, perhaps confident in their prospects, worked out an agreement with Smith to fast-track the case. The Supreme Court's decision to hear the case, combined with legal challenges to segregation in other states, gave some hope to William Monroe Trotter, the editor of the Boston Guardian, a Black newspaper.

"From the way our brethren at the south are entering into the fight against being jimcrowed out of their franchise, it seems that they have at last aroused themselves to the point of self-protection," Trotter wrote. "The better thinking people of the country are in sympathy with this action by the colored people."

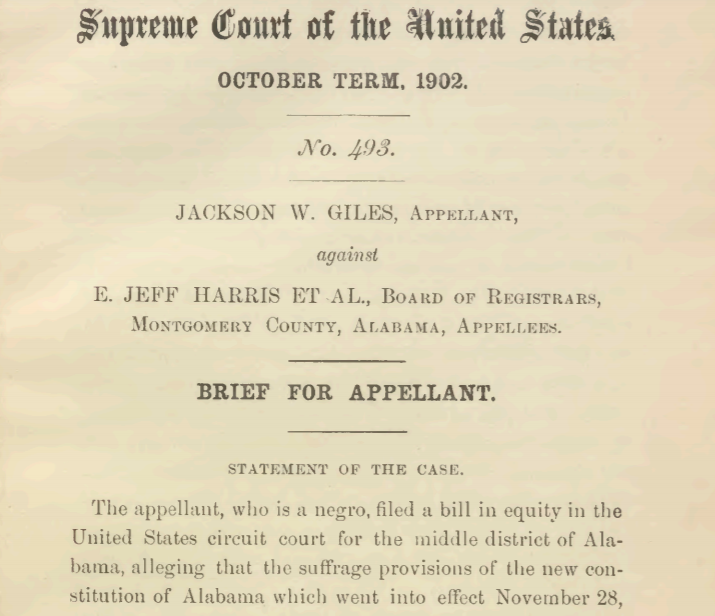

Smith’s brief to the nation’s high court focused on the jurisdictional issue. Since the Alabama Constitution was “in contravention of the 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution of the United States,” Smith argued, the federal courts were a proper place to hear the challenge.

The attorney wrote that the lower court had to consider the case because Giles' rights under the U.S. Constitution were under attack.

“A more high-handed and flagrant case of the nullification of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments to the Constitution of the United States and repudiation of their solemn guarantees to the negroes of America can never be presented to the courts of the country,” Smith wrote.

Without judicial action, Smith continued, the Black man had “only one other guarantee between him and actual slavery; that is the one contained in the thirteenth amendment.”

“What reason would he have to hope for protection under that one, should the southern states by similar methods undertake to deprive him of its guarantee?” he wrote.

‘To Hell for Grace’

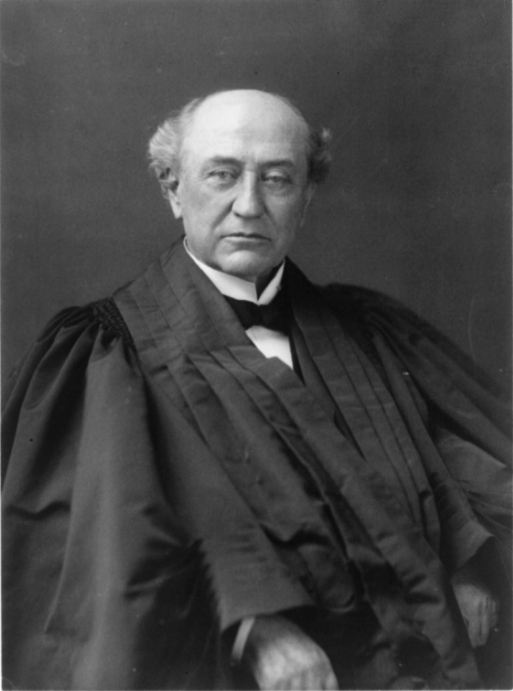

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. delivered the opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court on April 27, 1903. Holmes acknowledged that Alabama’s Constitution was “part of a general scheme to disfranchise” Black voters and referred to it as “wholesale fraud.” But instead of ordering Alabama to register Giles, Holmes and five of his fellow justices announced that the court could not enforce the provisions of the Constitution of the United States.

Holmes' reasoning followed a tortured circle. He first argued that enforcing Giles' rights under the U.S. Constitution would make the justices complicit in the fraud of the Alabama Constitution. If the court tried to force the state of Alabama to employ its voting provisions without regard to race, Holmes wrote, it would have put Giles under what Holmes called the “void instrument.”

“If, then, we accept the conclusion which it is the chief purpose of the (complaint) to maintain, how can we make the court a party to the unlawful scheme by accepting it and adding another voter to its fraudulent lists?” Holmes wrote.

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

Holmes went further. He said that Giles was not seeking his legal rights but looking for political relief, which the court could not give. Unless the justices wanted to “supervise the voting in (Alabama) by officers of the court” – and Holmes did not want that – it could do nothing.

“The (complaint) imports that the great mass of the white population intends to keep the blacks from voting,” Holmes wrote. “To meet such an intent, something more than ordering the plaintiff's name to be inscribed upon the lists of 1902 will be needed. If the conspiracy and the intent exist, a name on a piece of paper will not defeat them.”

The justice told Giles to find relief in the U.S. Congress. But Giles could not get relief from Congress because Alabama had barred Giles and most of its Black citizens from choosing their representatives.

“The court … sent the Negroes of Alabama to Congress for relief,” Smith later wrote. “It seems to be their way of disposing of the Negro by sending him elsewhere.”

Three justices took issue with Holmes’ reasoning. John Marshall Harlan, who had written a furious dissent in the Plessy decision, objected to Holmes’ decision on technical grounds, but added that Giles was “entitled to relief in respect of his right to be registered as a voter.” Justice David Brewer, in an opinion joined by Henry Brown (ironically, the author of the Plessy ruling) wrote that the federal courts could and should grant relief.

“(Giles) alleges that he is a citizen of Alabama, entitled to vote; that he desired to vote at an election for representative in Congress; that, without registration, he could not vote, and that registration was wrongfully denied him by the defendants,” Brewer wrote. “That many others were similarly treated does not destroy his rights or deprive him of relief in the courts. That such relief will be given has been again and again affirmed in both national and state courts."

Giles v. Harris, Pildes said, was “the last gasp” of efforts to stop Jim Crow.

“Giles is so kind of brutally candid in just saying we are not going to be able to do anything about this, because this is a massive political reality, because we don’t have the institutional tools which would be necessary to overturn all of this,” he said.

The Colored American magazine printed an editorial that said the court turned Black Americans over to “a Congress which is too busy making money for the trusts to listen to the cry of outraged humanity, or … to mercies of the very state which under the forms of law is robbing them of their rights for redress against the selfsame robbery.”

“Which is like sending a man to hell for grace,” the magazine said.

The aftermath

THE COLORED MAN'S Suffrage Association of Alabama pushed on as long as it could. Smith pressed the remaining cases in Alabama courts, and Giles continued fundraising, going as far as Kentucky to raise money for the cause. But the Alabama Supreme Court ruled against the plaintiffs, and in 1904, the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed Giles’ last appeal.

Giles ran a grocery store in Montgomery for a time. But he eventually gave up on Alabama. In 1907, Giles divorced his second wife, Mary. A few weeks later, Giles took out an ad in the Muskogee Daily Phoenix in Muskogee, Oklahoma, offering to sell a “cheap, return R.R. ticket to Montgomery, Ala.” Shortly after, Giles settled in nearby Taft, about 45 miles southeast of Tulsa.

Taft was one of Oklahoma’s “all-Black” towns, set up in the 1890s and 1900s in the hopes of providing safer lives for African Americans. Oklahoma was no better than Alabama for political or civil rights after 1910, but the all-Black towns offered a hope of economic independence. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, Taft grew from 250 people in 1907 to 772 in 1940.

“We had schools and everything back then,” said Leila Foley-Davis, who grew up in Taft in the 1940s and became its mayor in 1973, the first Black woman elected as a mayor in American history. “We had five stores, we had five churches.”

Giles remarried in 1912. He acquired land, raised cotton and served as a cotton agent for a time. And Giles stayed active in politics, running for justice of the peace in 1910 and attending Republican Party conventions throughout the decade. In 1918, Giles was a delegate at a convention to create a protective association for Black Oklahomans. It took place at Tulsa’s Dreamland Theatre, which white mobs destroyed in the Tulsa Race Massacre three years later.

Giles married a fourth time in 1934 and continued working into his 80s. In early June 1943, Giles, possibly suffering dementia, was admitted to the Taft State Hospital for the Negro Insane, a psychiatric facility that was understaffed, overcrowded and run by political appointees. A 1948 report said patients often slept on the floor, without sheets or with linen with "some question as to its cleanliness."

At some point during his stay, the 84-year-old Giles broke his leg. A blood clot formed, and on Aug. 1, 1943, Giles died at the hospital. Three days later, he was buried in his adopted town.

Neither the local press nor the era’s thriving national Black newspapers made note of Giles' death. His case had passed into the realm of dusty precedent. But the spirit that led to Giles' challenge was about to rise again. The year after his death, Montgomery’s Black community would mount a voter registration drive. The campaign drew many activists who would play major roles in the later Montgomery Bus Boycott. One was Rosa Parks, who lived in the same Montgomery neighborhood as Giles had.

They enjoyed more success than he did. But Giles' courage matched theirs. On November 8, 1904, long after his last legal defeat, Giles went to a Montgomery polling station and tried to vote.

“The beat managers of the election turned him down,” the Montgomery Advertiser reported the next day. “The board of registration of Montgomery County had refused him registration and, of course, the election managers could not permit him to vote.”

His denial was a foregone conclusion; the rivers had become too wide. But there Jackson Giles stood, unshaken amid the rising waters of racism and judicial cowardice, demanding his rights as an American.

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

/*LANDING*/#topper-6100386001 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-6100386001 .topper .topper__headline {text-shadow:none;}#content-6100386001 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-6100386001 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}/*JIMMIE*/#topper-7153822002 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-7153822002 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;text-align:center;}#topper-7153822002 .topper__meta {background-color:#000000;}#content-7153822002 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-7153822002 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}/*JAVONTE ESSAY*/#topper-5031895001 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-5031895001 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;text-align:center;}#topper-5031895001 .topper__meta {background-color:#000000;}#content-5031895001 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-5031895001 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}/*NBT ABOUT*/#topper-5147663001 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;padding-top:30px;}#topper-5147663001 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;text-align:center;}#topper-5147663001 .topper__meta {background-color:#000000;}#content-5147663001 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-5147663001 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}/*MELVIN*/#topper-7042889002 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-7042889002 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;text-align:center;}#content-7042889002 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-7042889002 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}/*RUGGLES*/#topper-8158701002 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-8158701002 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;text-align:center;}#content-8158701002 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-8158701002 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}/*ALAMO*/#topper-5704762001 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-5704762001 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;text-align:center;}#content-5704762001 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-5704762001 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}/*NEGRO LEAGUES*/#topper-6090010001 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-6090010001 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;text-align:center;}#content-6090010001 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-6090010001 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}/* BULOSAN*/#topper-6275193001 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-6275193001 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;}#topper-6275193001 .topper .topper__bump{margin-bottom:4em;}#content-6275193001 .component—pullquote {margin:14px 0px 44px 0px;}#content-6275193001 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-top:80px;}#content-6275193001 .words__name.svelte-13nupp6, .words__text.svelte-13nupp6{font-style:normal;color:#fbf4e5;font-weight:500;}#content-6275193001 .play-label.svelte-1tbzt8o{color:#d66432;text-transform:uppercase;font-weight:600;letter-spacing:0.05em;}#content-6275193001 .loading__bar.svelte-1ahs3ji.svelte-1ahs3ji{opacity:.65;}#content-6275193001 .progress.svelte-1rs4gjg.svelte-1rs4gjg{background:#000000;}#content-6275193001 .controls.svelte-1tbzt8o{padding:5px 15px 30px 15px;}#content-6275193001 .duration.svelte-1rs4gjg.svelte-1rs4gjg{text-shadow:none;color:#fbf4e5;font-weight:600;letter-spacing:0.05em;}/*LENA RICHARD*/#topper-8825616002 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-8825616002 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;}#topper-8825616002 .topper .topper__bump{margin-bottom:4em;}#content-8825616002 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-8825616002 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}/*JACKSON GILES LOCAL*/#topper-7995760002 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-7995760002 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;}#topper-7995760002 .topper .topper__bump{margin-bottom:4em;}#content-7995760002 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-7995760002 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}/*JACKSON GILES USAT*/#topper-9206016002 .topper__subheadline {font-family:"Unify Sans", sans-serif;}#topper-9206016002 .topper-caption__credit {padding-bottom:15px;}#topper-9206016002 .topper .topper__bump{margin-bottom:4em;}#content-9206016002 .custom-chapter-marker {margin-bottom:60px;}#content-9206016002 .component—cta:before {background-color:transparent;}

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Jackson Giles: How Jim Crow was challenged by an Alabama postal worker

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies